Background

Lyme disease in the United States typically presents with rash, fatigue, fever, headache, arthralgias/myalgias, central and peripheral neuropathies, and less commonly with central nervous system (CNS) manifestations such as meningitis/encephalitis.1,2 As the range of the Ixodes scapularis tick expands due to environmental pressures such as climate change, recognizing manifestations of tick-borne illness becomes increasingly critical to provide timely medical care to previously unaffected populations. A complete accounting of the disease’s manifestations is necessary to recognize manifestations. Lyme disease associated with pancreatitis was only reported twice before this case report.3 We present a unique case of acute pancreatitis secondary to Lyme disease in a mildly symptomatic, otherwise healthy young adult male. This case illustrates an exceedingly rare manifestation of Lyme disease.

Case Report

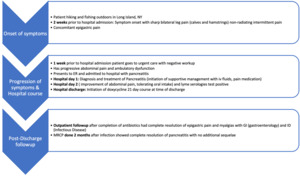

A 20-year-old healthy male presented to the hospital in early summer in Long Island, New York, with two weeks of acute onset, sharp epigastric pain that was constant and non-radiating. There was associated lower extremity pain extending from the posterior thigh to calf bilaterally that was symmetric, sharp, non-radiating, and present only when weight-bearing that began with the onset of the abdominal pain. He had no other constitutional symptoms. He had an initial decrease in appetite due to pain. The patient reported fishing, hiking, and spending time outdoors before admission. He denied any recent travel outside of New York State, traumatic injury, medical illness, a history of pancreatitis, or any tick bites. He denied alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drug use. Both the epigastric abdominal pain and bilateral lower extremity pain present on weight-bearing had been gradually worsening since onset, prompting a visit to urgent care one week after the symptom onset.

At the urgent care, the patient had a negative workup for Lyme, Babesia, Ehrlichiosis, Influenza, COVID-19, mononucleosis, HIV, hepatitis viruses, and herpes virus. Serum chemistries at that time were pertinent for mild elevations in alanine transaminase (ALT) and lipase without leukopenia or thrombocytopenia. The patient was sent home with acetaminophen. The patient had worsening abdominal pain and difficulty ambulating, which prompted reassessment at the Emergency Department.

In the hospital, the patient was afebrile with stable vital signs. The physical exam was pertinent for mild epigastric tenderness to palpation without guarding or rebound tenderness. There was no rash on examination. Labs demonstrated transaminitis with ALT 64(7-56 U/L), AST 24 (10-40 U/L), sodium 134 mmol/ml, total bilirubin 0.4mg/dl (n <1.2 mg/dL), direct bilirubin < 0.2mg/dl (m < 0.2 mg/dL), lipase 206 (n = <60), and leukocytosis of 14.22 x 109/L (n 4.5-11X109 /L). An abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of cholelithiasis or acute cholecystitis. The patient was given analgesics, intravenous fluids and subsequently admitted to the general medical floors for presumed acute pancreatitis after common etiologies of acute pancreatitis including alcohol, gallstones, medications (patient does not take any medications), hypercalcemia, traumatic, chemical exposures, and hereditary disease were ruled out.

On the general medical floor, the patient’s hyponatremia and transaminitis resolved. He had an extensive workup done that was unremarkable. Heterophile antibodies were not present and IgG subclasses 1-4 were within normal limits. An extensive autoimmune panel was negative. Testing for the presence of Babesia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia antibodies in the serum was negative. However, the patient’s EBV panel revealed an elevated EBV anti-viral capsid antigen (anti-VCA) IgM to >160 with negative EBV anti-VCA IgG with negative EBV PCR in blood. EBV IgM was considered to be a false positive. Computed Tomography (CT) scan revealed diffuse enlargement of the pancreas concerning for acute pancreatitis without peripancreatic fat stranding or fluid collections (Figure 1). Eventually, the patient’s Lyme immunoblot returned positive for five specific bands (66, 41, 39, 23, 18 kDa) of B. burgdorferi IgG as well as three specific bands (41, 39, 23) of B. burgdorferi anti-IgM, consistent with acute early infection by Lyme disease. The patient clinically improved and was tolerating oral intake. The patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis secondary to Lyme disease and subsequently initiated on a 21-day course of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily at the time of hospital discharge, which he completed outpatient. He had close follow-up with GI and infectious disease and had complete resolution of myalgias and epigastric pain after antibiotic completion. He had magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) done two months after follow-up, which showed the resolution of pancreatitis (Figure 2).

Discussion

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. It is transmitted via the bite of the Ixodes genus of ticks endemic to the eastern United States and parts of Eurasia, with an annual incidence in the United States of 40 per 100,000 people occurring mainly during the late spring to early fall.4 The incidence of Lyme disease has been increasing globally.5 Three stages characterize infection. Early, localized disease is characterized by the erythema migrans rash, the most common and typically first presenting sign of Lyme disease (but not always reported by patients), appearing 1-2 weeks after infection as an expanding erythematous skin lesion displaying a homogenous or targetoid appearance. Other early, localized disease features include fatigue, headache, fever, myalgias, and arthralgias. When left untreated, the disease can progress to an early disseminated stage after 3-12 weeks that is characterized by worsening erythema migrans rash, unilateral/bilateral facial nerve palsy, meningitis, carditis (classically with atrioventricular block), and migratory arthralgias. The late disseminated stage begins months to years after initial infection and is characterized by significant arthritis, encephalitis, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric manifestations.1,2 Appropriate treatment with doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime in children under 8, or ceftriaxone if there is cardiac involvement is curative, with only about 5-10% of patients reporting lingering symptoms of fatigue, arthralgias/myalgias after treatment lasting months or years.6

Our patient presented with mild epigastric pain and lower extremity myalgias in the setting of a largely unremarkable laboratory workup. Initial Lyme testing at urgent care may have been negative due to the type of test used, and a false negative result may have occurred; laboratory error and variability of detection depending on the strain of B. burgdorferi present may have impacted the test result. The patients presenting symptoms of lipase > 3 times the upper limit and clinical findings of epigastric pain were concerning for pancreatitis. All symptoms and pancreatitis (normal lipase and amylase levels at 1 month follow-up) resolved after doxycycline treatment. After ruling out common etiologies of acute pancreatitis, a CT scan of the abdomen revealed an exceedingly rare manifestation of Lyme disease, acute pancreatitis. Our patient had experienced lower extremity myalgias in the setting of his Lyme disease. The patient responded well to pain control and intravenous fluids as per standard of care treatment for pancreatitis and had additional resolution of his symptoms upon completion of his antibiotic course. In place of an alternative etiology to explain the development of pancreatitis in this otherwise healthy young male, the patient’s strongly positive Lyme serology followed by confirmatory Western blot suggests Lyme disease as the etiology of this patient’s pancreatitis. Additional cases of pancreatitis due to Lyme disease have been described. Ahmed et al. described a case of a 20-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain and body aches after camping in upstate New York, where she had a tick bite.7 She developed symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and fever, leading to hospital admission, where pancreatitis was diagnosed with elevated lipase levels. The patient also had a characteristic rash (erythema migrans) associated with Lyme disease. Baisse et al. described a 49-year-old forest worker who presented initially with fever and abdominal pain.3 Recurrent admissions led to the discovery of pancreatic necrosis and a pseudocyst, eventually diagnosed as pancreatitis linked to Lyme disease due to positive serology and a characteristic skin lesion. The case underscores the diverse manifestations of Lyme disease, including rare presentations like pancreatitis, and the importance of considering Lyme disease in the differential diagnosis, especially in endemic regions. These cases highlight the challenge of diagnosing Lyme disease, as pancreatitis is a rare manifestation. It suggests exploring other potential manifestations of Lyme disease due to its multisystem nature. The pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis secondary to Lyme disease is unknown, and further research should be pursued.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

Corresponding Author

Rasan K Cherala MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of Hospital Medicine

Stony Brook University Hospital, NY

Email: rasan.cherala@gmail.com