BACKGROUND

Turmeric (Curcuma longa), a widely used culinary spice, has gained popularity as an herbal supplement for its purported health benefits, largely attributed to its active component, curcumin. The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of curcumin have been touted to reduce atherosclerotic disease burden, slow the progression of chronic kidney disease, and maintain remission in inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis.1–3 The promising anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin have led to increased consumer use. However, with the lack of standardized regulations for herbal supplements, turmeric’s potential side effects and toxicity remain largely unknown.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 53-year-old woman with Behçet disease and depression was sent to the emergency department by her primary care provider for elevated liver function tests (LFTs). The patient reported new-onset dark-colored urine despite maintaining adequate hydration. Outpatient urinalysis was negative for any signs of a urinary tract infection, but liver enzymes were markedly elevated. The patient reported having mild fatigue for the past month, but otherwise denied abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, itching or confusion. On medication review, she reported taking a Kirkland Signature Turmeric supplement daily for four months, and Sertraline 200 mg daily for years. She did endorse drinking 3-4 beers on the weekends.

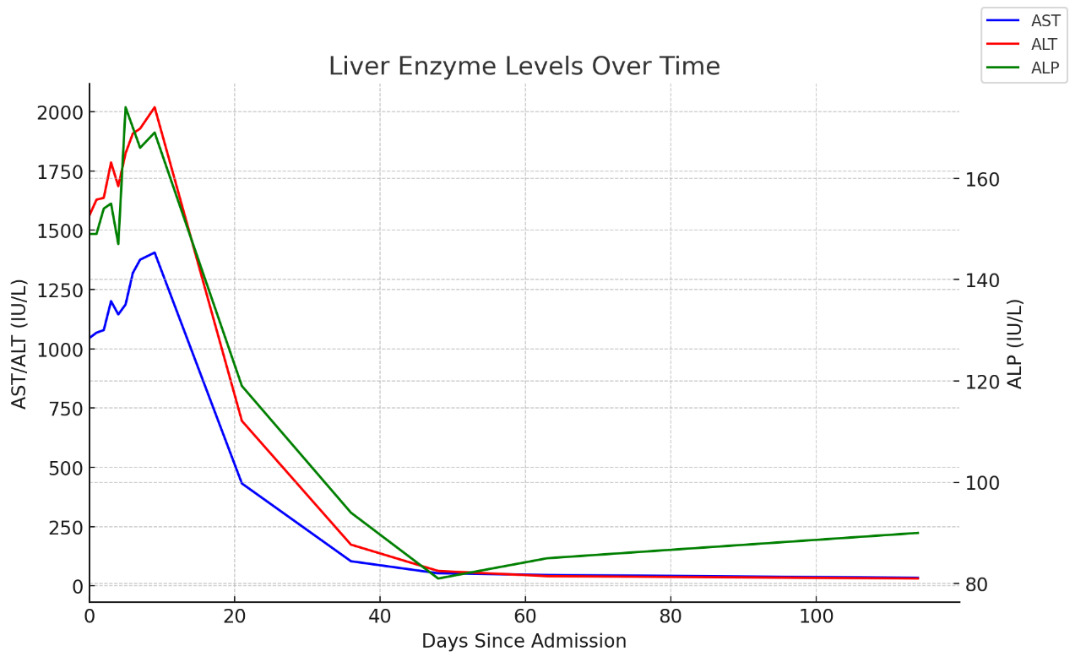

On exam, the patient was hemodynamically stable with blood pressure ranging from 120-150s/70-80s throughout the visit without any clinical evidence of shock. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. She did not have any scleral icterus, jaundice, rash, asterixis, abdominal tenderness, or hepatosplenomegaly. On admission, labs were notable for elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 1045/1560 IU/L, respectively (normal: AST 0-32 IU/L, ALT 0-33 IU/L), elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) at 159 IU/L (normal: 0-40 IU/L), mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) at 149 IU/L (normal: 39-117 IU/L), but normal bilirubin, INR, and platelet count. Upon initial assessment, the patient presented with hepatocellular liver injury based on an R factor of 47.7 with concern for drug-induced liver injury (DILI); however, differential diagnoses included viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and vascular causes such as Budd-Chiari Syndrome in the setting of Behçet disease.

Negative workup included: liver ultrasound (U/S), portal vein U/S, computed tomography scan of the abdomen, urine toxicology, serum acetaminophen and ethanol level, viral serology (hepatitis A, B, & C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and herpes simplex virus), autoimmune serology (antinuclear antibody, antimitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody, F-actin, IgG levels, and Celiac disease antibodies), and hereditary causes (Wilson’s disease, hereditary hemochromatosis, and alpha-1-antitrypsin). Portal and hepatic vein U/S were obtained to rule out Budd-Chiari Syndrome as Bechet’s disease is associated with hepatic vein thrombi. Within 24 hours of admission, the turmeric supplement was stopped, and the patient was started on a N-acetyl cystine (NAC) protocol. NAC was stopped as patient began having abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and hot flashes without any shortness of breath, wheezing or hives shortly after treatment initiation. The patient was started on NAC as treatment has been shown to reduce overall hospital length of stay, improve transplant-free survival and overall survival in non-acetaminophen-related acute liver failure.4 Her LFTs continued to rise prompting a liver biopsy for etiology. Histology showed moderate to marked lobular, portal and interface hepatitis, without any hepatocyte collapse consistent with DILI, as shown in Figure 1. The patient’s LFTs peaked six days into her admission, and she was subsequently discharged with indefinite discontinuation of turmeric supplements. Patient’s LFTs normalized within four months of discontinuing the supplement returning to baseline (AST/ALT/ALP 34/31/90 IU/L), as seen in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

This case demonstrates the importance of maintaining a broad differential in the workup of any pattern of liver injury. Anchoring bias remains a common cause of delayed diagnosis in medicine. The patient’s history of Behçet disease prompted a thorough workup to rule out autoimmune and ischemic causes associated with Behçet disease before considering DILI. A thorough review of medications and herbal/dietary supplements is essential to conduct in all cases of liver injury. In this case, the patient was taking sertraline for years, and the improvement of LFTs after turmeric cessation while continuing sertraline supports turmeric being the culprit agent. The Naranjo adverse drug reaction (ADR) probability scale, a scale used to assess causality for ADR, score was 7 indicating a probable reaction to turmeric given reasonable temporal sequence of LFT elevation after supplement initiation, resolution of LFTs after withdrawal of turmeric, and lack of alternate causes for hepatocellular liver injury. On careful examination of the Kirkland Signature Turmeric supplement, a daily serving of the supplement contains 1000 mg of Turmeric (Curcuma longa) root extract, and 10 mg of black pepper (Piper nigrum) fruit extract to enhance the bioavailability of the curcuminoid compounds. Black pepper has not only been shown to improve gut absorption of curcuminoids, but studies suggest that piperine reduces first-pass elimination by inhibiting the liver’s ability to metabolize curcumin, hence increasing its bioavailability to toxic levels.5

Analysis of the Italian Phytovigilance system, a larger-scale database that records adverse reactions to food supplements, reveals trends in turmeric-associated toxicity that are seen in our case.5,6 Data from the Italian Phytovigilance system and the scarce case reports available indicate that women are predominantly affected by turmeric-induced DILI, with a median age of 55-56 years.5–8 The time from supplement initiation to DILI diagnosis varies, with a median duration of about two months.5,6 Recovery after stopping turmeric supplements typically spans several weeks to a few months, depending on severity and individual patient factors. This is in line with our patient, who began turmeric supplementation four months before hospitalization due to its reputed anti-inflammatory effects.

Unlike pharmaceuticals, many herbal supplements are not subject to the same rigorous regulatory oversight by agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States. This can lead to inconsistencies in safety marketing, ingredient labelling, and correct dosing, thus increasing the risk of prolonged toxicity exposure and delayed intervention. Therefore, higher regulatory standards are needed to further examine therapeutic and toxic dosing of commercially available herbal supplements that incorporate bioenhancers.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

Corresponding Author

Alan Abboud, MD

Department of Medicine

Stony Brook University Hospital

Stony Brook, NY

Email: alan.abboud@stonybrookmedicine.edu