Background

Frequently admitted patients (i.e., ‘high utilizers’) comprise a small percentage of all patients yet consume a relatively large proportion of hospital resources. In healthcare, high utilization refers to patients frequently admitted to hospitals, often staying longer than average. These patients also make frequent emergency department visits and require intensive care or specialized treatments. This pattern highlights significant demands on healthcare resources and the need for effective management.1 High utilizers have been found to more likely to be female, suffer from more chronic disease and mental illness, and have lower levels of income and education than their peers.2,3 They have also been shown to not receive effective care coordination or sufficient preventative health services.4

Referred to elsewhere as “super-users,” high utilizers have been reported to benefit from targeted services aimed at improving quality and reducing cost of care.5 Individualized care plans have also been shown to reduce the cost of care for high utilizers.6 Numerous other patient-focused interventions have been reported, including home care delivery, patient liaisons, community social resources, and personal health goal development. Other reported interventions include programs aimed at targeted populations (e.g., patients with diabetes mellitus) and programs aimed at providing more consistent care across healthcare setting and between providers4,7,8

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic our hospital was struggling with overcrowding, and at one point declared ‘crisis standards of care.’ As with many other hospitals at the time, we simply did not have enough beds and nurses to meet the community demand for hospital care. So, in 2021 our division embarked on a quality improvement project aimed at reducing hospital resource utilization by implementing individualized care plans (ICPs) for high utilizers.

Methods

The project was implemented by a hospitalist group in a large Midwest academic medical center with 718 acute care beds, spanning 2021-2022. The workgroup selected five principles to guide decision-making, including (1) improving patient quality of life; (2) optimizing patient health span; (3) minimizing patient harm; (4) increasing patient time spent out of hospital; and (5) provide more consistent patient care when in the hospital. This project focused on the fourth principle as our primary aim.

A report in the electronic health record (EHR) identified frequently admitted patients, defined as having greater than seven admissions over the previous 365 days. We chose seven admissions because we believed this high enough to provide measurable impact. Twenty-four patients populated the initial report. A workgroup of seven hospitalists, many of whom had leadership roles within the hospital, then selected twelve patients from the report who were relatively young and whose admissions were often minimal risk for serious adverse events. To address this, we employed a within-subjects design, using patients as their own controls. We compared their LOS and other relevant metrics from the previous year to the current year, during which the intervention was implemented. This approach allowed us to provide a clearer assessment of the intervention’s impact. The most common reasons for admission were pain, nausea with vomiting, dyspnea, and alcohol intoxication or withdrawal. Common chronic conditions among these patients included chronic pancreatitis, sickle cell disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic adrenal insufficiency, and alcohol use disorder. Notably, opioid use disorder was also present or suspected in most cases.

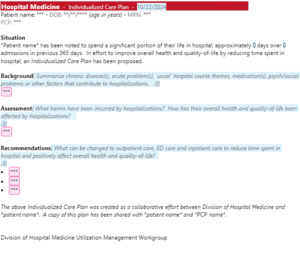

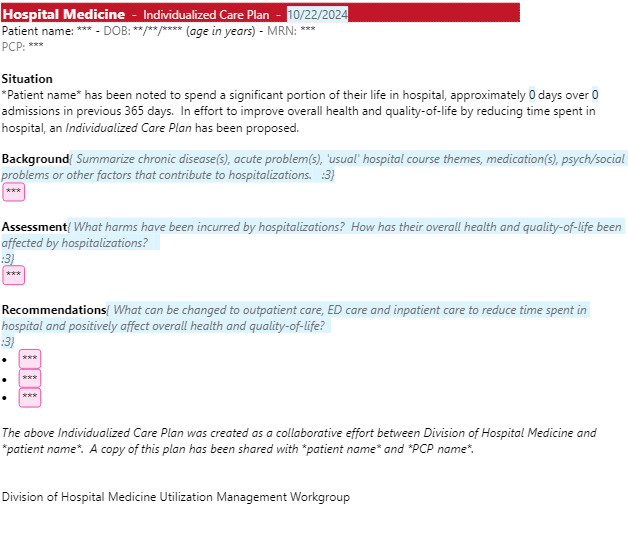

Selected patients were reviewed and discussed within the group, with input sought from additional care team members (e.g., primary care provider, specialists, nursing, etc.) when indicated. An individualized care plan (ICP) was then developed for twelve patients in this project’s initial phase (Figure 1). ICPs were documented in a standardized fashion using a newly created note template. The note template used rule-based tools to auto-populate the number of admissions and days in hospital over the previous 365 days. The template also used “vanishing tips” to help guide documentation in SBAR format (i.e., situation, background, assessment, recommendations); the tips were automatically removed upon note signature (Figure 2).

Patients were made aware of the presence of an ICP in their chart. All patients provided input for their ICPs and most patients agreed with the entirety of the plans. However, a small minority of patients did not agree with all recommendations proposed in their ICPs. In these cases, ongoing discussions were had with the patient, their family or advocate, and other care team services to align all parties to an agreed-upon, evidence-based plan. None of the patients for whom ICPs were created were excluded from ongoing ICP implementation. A note was placed in the “FYI” (i.e., for your information) section of the EHR so that it would be easily accessible by all members of the care team. The presence of an ICP was flagged and hyperlinked from numerous locations using EHR rule-based tools (Figure 3).

Patients were followed for at least one year. Additional follow-up communications between the ICP workgroup, patients and the care team occurred and, in some cases, ICPs continued to be modified as needed. Admissions per year, days in hospital per year, and days in hospital per admission were tracked. The primary goal was to reduce the number of days in hospital per year by 50%.

Results

The mean age of patients involved in the project was 35 years. Six patients were female; six were male. Total admissions per year decreased from 125 to 41 (-67%) admissions, and total days in hospital per year decreased from 497 to 219 (-56%) days. Therefore, this group of twelve patients spent 278 fewer cumulative days in the hospital following the implementation of an ICP, which was an average of 23 days per patient. From the hospital perspective, an inpatient bed was freed for use by other patients for more than nine months.

While days in hospital per year decreased as above, the number of days in hospital per admission increased from 4 to 5.4 (+26%) days. No deaths occurred in the follow-up period.

Discussion

The project achieved its primary goal of decreasing total hospital days by over 50% among the selected high utilizers, potentially enhancing their quality of life by providing more time outside the hospital, although direct measurement of this impact was not undertaken. Post-intervention, patients experienced a 1.4-day increase in the length of stay per admission, possibly due to fewer brief admissions for low-risk illnesses. For example, many of the patients presented with acute pain. We reason that due to the ICP, the non-severe pain episodes were more appropriately triaged to the outpatient setting, while more severe episodes necessitating hospitalization were admitted, and the overall LOS was skewed longer as a result. We also do not believe the presence of ICP steered providers to be biased toward longer LOS. A future study could look at metrics that evaluate complexity of stay, such as case mix index, to further correlate this.

A distinctive aspect of the project was the strategic use of the EHR for patient identification, documentation, and communication. This involved tools such as a report identifying frequently admitted patients, a documentation template auto-populating admission details, vanishing tips for note authors, a custom patient list column flagging patients with an ICP, and navigational hyperlinks to the ICP. ICP awareness was in issue early on in this project, as providers were not consistently aware that a high utilizer had an ICP. To address this, ICPs were prominently “flagged” in multiple locations within the EHR, including a patient list column, admission tracker, patient chart header, initial visit note template, and electronic handoff tool. This accessibility was crucial to the project’s success.

There were several lessons learned from this quality improvement project:

Lesson 1: Substance use disorder, notably opioid use disorder, significantly contributed to frequent admissions among high utilizers. Nearly all patients in this project had previously been prescribed maintenance opioid therapy, and most were suspected to have developed opioid use disorder. Acute exacerbation of chronic pain was the most common reason for admission for these patients, despite efforts to facilitate clinic-based management. It was suspected that easy and quick access to intravenous medication played a prominent role in patient preference for hospital care over clinic care.

Lesson 2: Managing chronic health issues in high utilizers solely from the hospital posed challenges. Resources like inpatient consults, follow-up appointments, and specialist referrals were frequently offered but declined, and adherence to medical recommendations was often poor, thus showing that the offer of “more” resources was not always impactful. Additionally, it was not clear if patients simply sought their care elsewhere and thus had less impact on their overall burden of hospitalization.

Lesson 3: Provider prescribing behavior can be difficult to change. Adjusting the unconditional prescription of controlled substances, especially opioids, was needed to break the pattern of recurrent hospital admission. However, some providers were hesitant to withhold certain medications, particularly opioids, citing lack of time to discuss risks and benefits and fear of patient dissatisfaction or legal consequences.

Lesson 4: Sustainability of projects for high utilizers can be challenging. It’s important to regularly monitor for ICP use, seek feedback from providers who have recently implemented an ICP, and update ICPs as needed when circumstances change. This time-intensive, manual input was done solely by our hospitalist providers, and therefore competed with various other clinical and non-clinical duties. A robust and dedicated team would need to be maintained, with a cadence of review and update for each individual ICP at least yearly. This also limits the number of patients who can have ICPs implemented.

Considering the sustainability of the project, especially in terms of ongoing commitment, resource allocation, and scalability, is vital for the long-term success of similar initiatives. Future research on this topic could focus on more direct measurements of patient quality of life and health impact, or report on cost savings to the hospital. In conclusion, identifying appropriate patients and creating easily accessible ICPs can enable more time outside the hospital for patients, while simultaneously freeing up valuable hospital resources for the community.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

Corresponding author:

Nicholas Weiland, DO

Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine

University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE

Phone: 712-541-8901

Email: Nicholas.weiland@unmc.edu