Background

In-situ thrombosis of the pulmonary artery was first described in the 1950s as a rare cause of a filling defect in a pulmonary artery and offered a different diagnosis to the most common cause of a pulmonary artery filling defect, an embolism.1 Thrombus in-situ offers a diagnostic alternative for filling defects in the pulmonary artery, and has been associated with chronic pleural effusions, pulmonary resections, SARS-CoV-2 infection, trauma, sickle cell disease, caseating/invasive infections, vasculitis, sequela of radiation therapy and cardiopulmonary conditions that result in pulmonary hypertension.2 Herein, we present a rare case of a pulmonary artery thrombus in-situ adjacent to rounded atelectasis.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old male with a medical history significant for peripheral and coronary artery disease status post coronary artery bypass grafting, bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction presented to the hospital after a fall and a two-day history of increasing generalized weakness, a productive cough as well as worsening shortness of breath in the last 24-hours. When he was admitted, he was tachycardic at 104 beats per minute, tachypneic at 24 breaths per minute with oxygen saturations at 96% on 2 liters of supplemental oxygen through nasal cannula; his blood pressure was otherwise stable at 124/82mmHg, and he was afebrile. His physical examination was notable for increased work of breathing with use of respiratory accessory muscles, diffuse rhonchi, and scattered rales. His blood work was remarkable for a leukocytosis at 13.2 x 103/mcL (normal range: 4-11 x 103/mcL) , an elevated brain natriuretic peptide at 1959 pg/mL (normal <100 pg/mL) and an initial high sensitivity troponin level of 12 ng/L (normal < 36 ng/L). His testing for Influenza A/B, SARS-CoV-2, and RSV were negative; a full respiratory panel was not obtained.

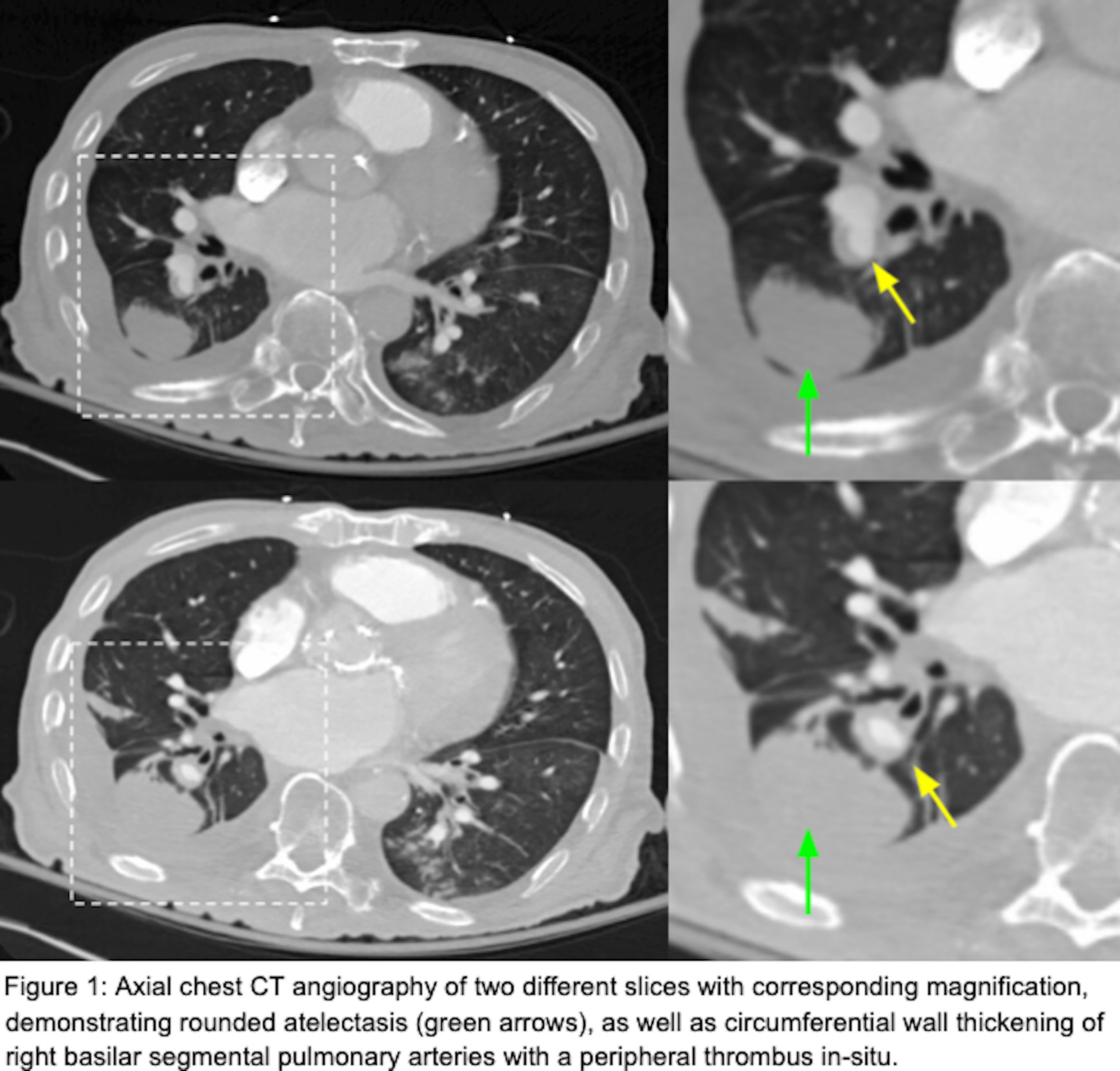

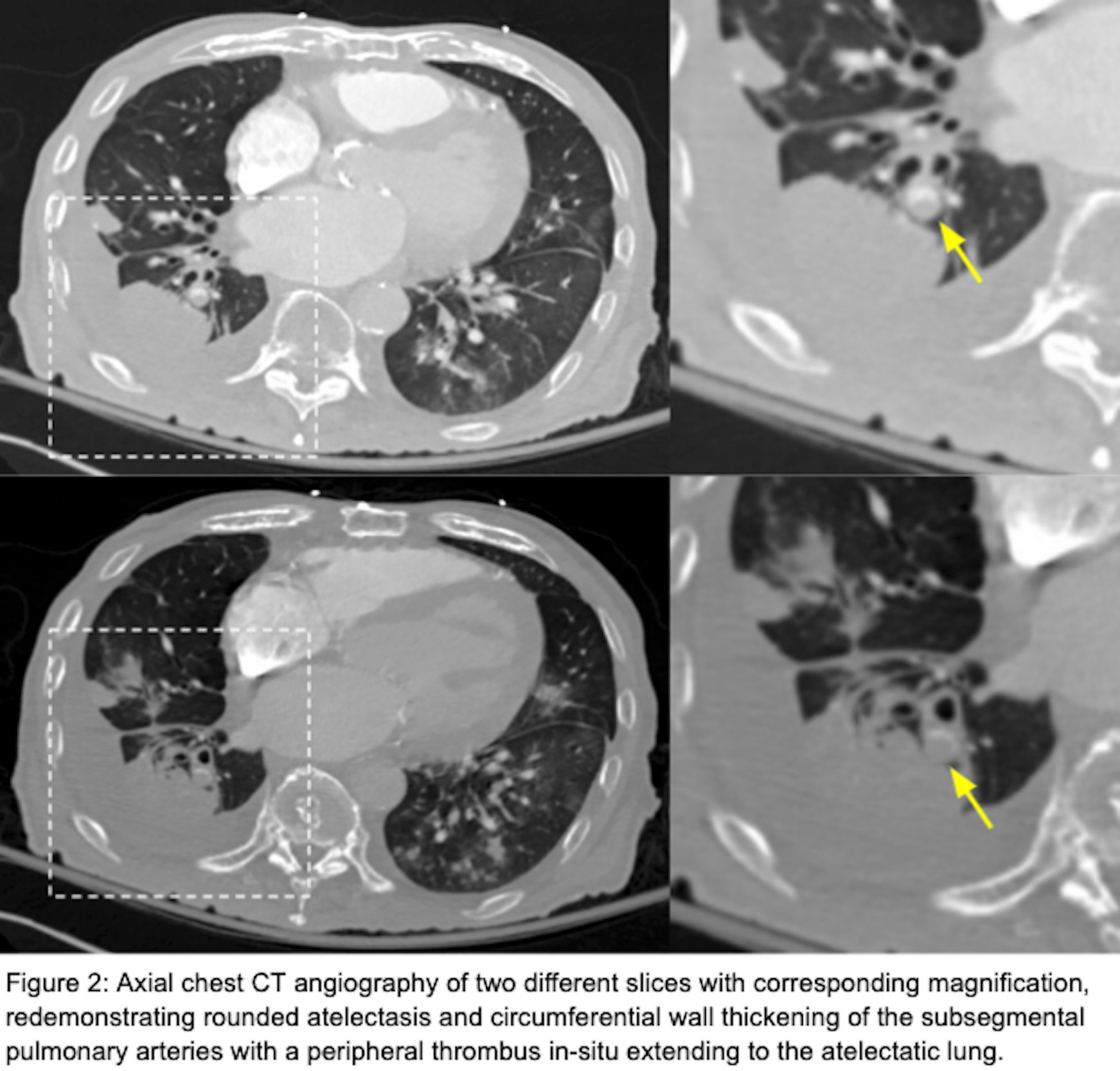

He had a chest radiograph on admission demonstrating patchy bibasilar opacities, with small bilateral pleural effusions which were greater on the right. Chest computed tomography angiography (CTA ) demonstrated a small chronic loculated right-sided pleural effusion with pleural thickening and pleural calcifications. Adjacent to this pleural effusion, there was a round opacity with evidence of volume loss and a comet tail sign compatible with rounded atelectasis. There was also demonstration of circumferential wall thickening of right basilar segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arteries with a peripheral thrombus within both of these pulmonary arteries extending to the rounded atelectasis (Figures 1 and 2). This was favored to represent an in-situ thrombus over a pulmonary embolism. Additional findings were concerning multifocal pneumonia versus aspiration, a second area of rounded atelectasis in the right middle lobe, subpleural reticular opacities, cardiomegaly, mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, and a small left pleural effusion. His CT imaging was then followed by a bilateral lower extremity venous duplex ultrasound, which was negative for evidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT). A formal echocardiogram revealed a moderately dilated left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 15%, moderately dilated right ventricle with severely reduced systolic function, moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation and normal pulmonary pressures. Imaging from one year prior to this admission demonstrated unchanged right lower lobe rounded atelectasis with no radiographic evidence of a thrombus in this area, although this is of limited interpretation due to the type of study performed. A previous echocardiogram from one-year prior revealed mitral regurgitation, and a globally hypokinetic left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 20-25%.

The pulmonology team recommended no intervention regarding both the rounded atelectasis and the in-situ thrombus. The rounded atelectasis was chronic in nature and the in-situ thrombus only affected smaller vessels and therefore, was not felt to be contributing to this patient’s acute dyspnea. Furthermore, he was considered high risk for immediate or long-term anticoagulation given his history of falls, age and concurrent antiplatelet medication. He completed empiric antibiotic treatment for aspiration pneumonia and was ultimately transitioned to hospice care given his multiple admissions due to severe dysphagia and significant deconditioning with failure to thrive.

Discussion

This case report identifies a patient with right-sided rounded atelectasis with in-situ thrombus in the supplying segmental and subsegmental arteries, a rare radiological finding. Both the rounded atelectasis and in-situ thrombus likely did not contribute to this patient’s acute respiratory decline, as the rounded atelectasis was demonstrated to be unchanged over a one-year interval; further, the thrombus was located in the periphery in segmental/subsegmental arteries supplying the rounded atelectasis, an area which was contributing to anatomical dead space. Additionally, image-based signs suggestive of an acute pulmonary embolism were not observed. These include pulmonary artery dilation proximal to the thrombus and a central filling defect with acute angles within vessel walls.3 Moreover, signs suggestive of a significant pulmonary embolism causing tricuspid regurgitation, or retrograde contrast flow into the inferior vena cava were not observed. On the contrary, we did observe pulmonary artery wall thickening without proximal dilation and a filling defect with obtuse angles surrounding the thrombus, which suggests this was not an acute thrombus but rather chronic. Collectively, these findings represent chronic changes and are interesting radiological findings. The association between rounded atelectasis and in-situ thrombus has not been previously described in a recent review2 or found elsewhere in the literature.

Rounded atelectasis, also known as Blesovsky syndrome and pleuroma, is an uncommon type of peripheral atelectasis where redundant pleura folds on itself, creating a mass-like consolidation observed on CT imaging. Typical CT features associated with rounded atelectasis include a peripherally located, round or ovoid lesion of soft tissue density in contact with abnormal pleura (either pleural effusion or pleural thickening), with associated volume loss and distortion of the bronchovascular bundle appearing as a “comet tail”.4 Some appearances of distortion of the bronchovascular bundle can also appear as “crowfeet”.4 Given their radiologic similarities, lung malignancies must be considered when assessing rounded atelectasis. Overall, our patient’s findings on CT exhibited typical features consistent with rounded atelectasis, and past imaging confirmed an unchanged appearance compatible with atelectasis and not a malignant process.

Virchow’s triad of thrombosis, states that endothelial injury/inflammation, stasis, and hypercoagulability are predisposing factors for intravascular thrombosis.5 The current proposed mechanism for in-situ thrombosis originates from local hypoxia and inflammation, which promotes de novo thrombus in the pulmonary arteries.6 In our case, rounded atelectasis likely created a local area of inflammation, coupled with this, within chronic atelectasis there may be a ventilation/perfusion mismatch, limiting blood flow through an atelectatic lung.7,8

Overall, this would significantly increase the risk of intravascular thrombosis. We can therefore postulate that the artery supplying an area of rounded atelectasis is predisposed to forming an in-situ thrombus. To our knowledge, there have been no reported cases of rounded atelectasis with in-situ thrombus in its supplying pulmonary artery. However, given that the diagnosis of in-situ thrombus remains underappreciated and underrepresented in CT angiography in general,2 there exists a possibility that cases of in-situ thrombus have been mislabeled as a pulmonary embolism (PE). Therefore, when considering PE studies, it is important to remain vigilant for cases of in-situ thrombus. PEs and in-situ thrombosis are distinct entities with different pathophysiology and clinical implications including treatment plans. For example, PEs are typically treated with thrombolytics, thrombectomy, or more commonly with intravenous or oral anticoagulation.9 Conversely, with PEs within subsegmental arteries, and no evidence of DVT within the legs, clinical surveillance is recommended over anticoagulation.9 Treatment for in-situ thrombus on the other hand, will depend on the location, size of the thrombus, history and or presence of thrombophilia in addition to the overall clinical scenario.2 In our case the thrombus was located in the periphery at the subsegmental artery, although extending proximally; we recommended conservative treatment in line with CHEST guidelines,9 in addition to consideration of the patient’s goals of care and anticoagulation risk. Recognizing the differences between PE and in-situ thrombus is crucial for appropriate management, as anticoagulation strategies will differ according to diagnosis.

In summary, this case report highlights the rare occurrence of in-situ pulmonary artery thrombosis adjacent to rounded atelectasis. This case underscores the necessity for careful clinical and radiological assessment in patients presenting with complex pulmonary findings, and advocates for heightened awareness of in-situ thrombus as a differential diagnosis.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Corresponding Author

Kyle Rollheiser, MD

Kent Hospital/Brown University Internal Medicine Residency Program

455 Toll Gate Road, Warwick, RI 02886

Email: kyle_rollheiser@brown.edu.