Background

Erythromelalgia is a rare disorder characterized by a triad of severe sudden bilateral symmetric paroxysmal extremity burning pain, erythema, and increased skin temperature in the extremities. Symptoms can appear in any part of the body, most frequently affecting the feet, hands, and legs. Erythromelalgia is challenging to treat, with patients requiring multimodal pain regimes to manage symptoms that otherwise lead to severe disability, increased morbidity, and mortality.

Case Presentation

A woman in her mid-70s arrived at the hospital three weeks after undergoing rotator cuff surgery, reporting worsening bilateral leg pain accompanied by swelling, redness in her legs, and purple discoloration of her toes. Her past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease secondary to a sliding hiatal hernia status post-repair, and idiopathic erythromelalgia. Since her diagnosis three years ago, she has had frequent erythromelalgia flares characterized by erythema, pain, and paresthesias on her feet, hands, and face. Prior to her admission, the patient had reached out to her primary care provider, who prescribed loop diuretics and antibiotics to treat the bilateral leg edema and erythema without clinical improvement noted.

Upon initial examination, a blanchable regional patch with indistinct borders extending from below the knee to the toes was identified on both legs. This patch was associated with xerosis around the ankles and diffuse pitting edema in the affected areas (Figure 1). The area was warm to touch and exquisitely painful both to superficial palpation and active and passive motion. Her toes were distinctly cyanotic, with overlying areas of xerosis and ulceration.

The acuity of the clinical picture, the extent of the edema, the severity of the pain, and recent post-operative immobility guided the initial workup. The differential diagnosis remained broad. An ankle-brachial index and pulse volume recording (ABI/PVR) revealed normal arterial blood flow and a lower extremity Doppler ultrasound revealed no deep vein thrombosis. Systemic etiologies of bilateral lower extremity edema were ruled out, with normal liver function tests (albumin level 3.7 g/dL), and a transthoracic echocardiogram revealing no significant valvular abnormalities, and a preserved ejection fraction (70%, unchanged from prior). The negative workup led to a working diagnosis of atypical erythromelalgia flare.

A thorough medication history revealed a possible temporary association between aspirin and disease control, with flares beginning soon after the patient stopped the medication in preparation for hiatal hernia repair and orthopedic surgeries. However, the reintroduction of the aspirin was delayed as part of the treatment plan devised by the clinical team and the patient. After discussing the initial medical treatment, the patient requested that the reintroduction of aspirin be delayed until after alternative diagnoses were ruled out, as she had worries that she could respond adversely to the medication. After a negative workup for other causes, a test of treatment was performed, restarting aspirin 325 mg/day alongside a multimodal pain management strategy, including amitriptyline 50 mg at bedtime and lidocaine patches.

Over the following days, her clinical picture improved. The severity of the pain declined to tolerable levels, the bilateral leg numbness subsided, and the lower extremity edema and erythema decreased, leading to improved leg mobility. The patient was discharged on the newly instituted regime plus a topical amitriptyline-ketamine preparation and close outpatient follow-up with rheumatology. Three months later, the patient was seen in the outpatient setting. Her leg edema and pain improved, but the erythema persisted. She decreased the dosage of oral amitriptyline to 25 mg/day due to medication-induced hallucinations at night and stopped the topical amitriptyline-ketamine cream due to xerosis. A skin moisturizer was added, and the oral amitriptyline prescription was modified to 25mg at bedtime. Six months after her discharge, her erythema resolved. She continues to follow up at our institution.

Discussion

Erythromelalgia, first described in 1878, is a rare disorder characterized by paroxysmal pain and erythema in the extremities.1 Epidemiologic studies have estimated an annual incidence of between 0.36 and 1.3 per 100,000 people.1,2 First thought to be a single entity, erythromelalgia was subsequently subdivided into primary, secondary, and idiopathic forms, with the identification of SCN9A mutations defining primary cases of the condition.1,3 Secondary erythromelalgia has been found in association with myeloproliferative, vascular, connective tissue, musculoskeletal, and neurologic disorders, as well as in relation to the consumption of certain drugs.1,4 Interestingly, the onset of erythromelalgia precedes the first identification of myeloproliferative disorders by 2.5 years on average.4

The pathogenesis of erythromelalgia is thought to result from a complex interaction between the nervous and the vascular system,5 brought about by the ineffective function of voltage-gated sodium channels in the case of primary forms,3 and arteriolar structural changes in myeloproliferative disorder-associated presentations.1,6 Non-hereditary Erythromelalgia is considered a neurovascular disorder, with studies reporting on abnormalities in cutaneous microvascular function and thermoregulatory control, autonomic function tests showing a component of small fiber neuropathy, and pathologic reports revealing a thrombotic component further contributing to the microvascular disturbance, primarily when associated with myeloproliferative disorders.1,6,7 Erythromelalgia has been associated with entities such as systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, and myeloproliferative disorders like polycythemia vera and essential thrombocytosis.8 Some reported triggers include certain antineoplastic agents (i.e., osimertinib), calcium channel blockers (notably nifedipine and verapamil), and rarely topiramate or other neuromodulators.1,9,10

We present a case of a female patient with a known history of Erythromelalgia and documented flares triggered by surgical interventions. Her case was noteworthy, as the distribution of the pain and swelling was atypical for Erythromelalgia. Regardless of the underlying cause, patients with erythromelalgia classically present with a triad of severe, sudden, bilateral, symmetric, paroxysmal burning pain, erythema, and increased skin temperature in the distal extremities, as well as swelling and numbness of the affected area.1,4,11 Exposure to cold temperatures and limb elevation typically provides relief, while exercise, warmth, and nighttime worsen the severity of the presentation.1,4 Physical examination findings include blanching erythema, acrocyanosis, digital ulceration, and a reticular cutaneous pattern in the affected areas.4

After ruling out alternative diagnoses, the clinical presentation of our patient was determined as being secondary to an erythromelalgia flare. There are no formal diagnostic criteria for erythromelalgia.12 Nevertheless, clinical hallmarks1 are sometimes used as such, including burning extremity pain, pain aggravated by warming, pain relieved by cooling, erythema of the affected skin, and increased temperature of the affected skin. The differential diagnosis of erythromelalgia includes common mimics such as erysipelas, stasis dermatitis, and deep vein thrombosis, as well as specific presentations of peripheral neuropathy, vasculitis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Fabry disease, and, in post-surgical patients, complex regional pain syndrome.12,13 From these, the latter two resemble the clinical presentation of Erythromelalgia the closest, with other etiologies approximating its symptoms only partially.12 Ancillary tests should be considered only in select cases and directed towards ruling out alternative causes, and comfort and symptom exacerbation must be weighed against diagnostic utility.14

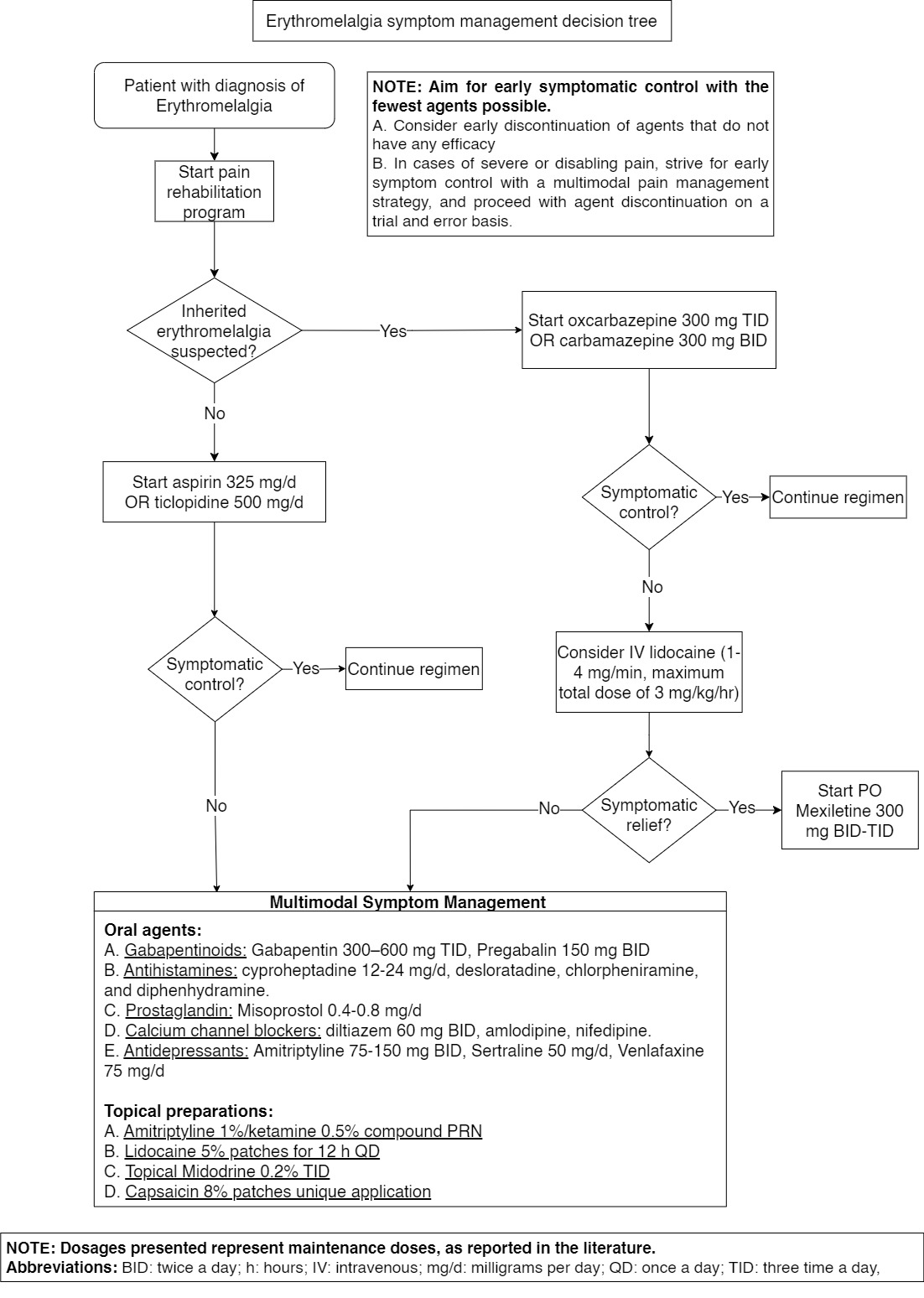

The management of Erythromelalgia is complex, virtually limited to pain relief, and often requires a multimodal strategy with multiple agents to achieve symptomatic control.12 A state-of-the-art review recommends a stepwise approach to trial pharmacotherapy.12 For patients with inherited erythromelalgia, oxcarbazepine or carbamazepine can be used.12 If either proves ineffective, lidocaine infusion followed by mexiletine may provide relief.12 Additional treatment with gabapentin may be considered with the aim of treating central causes of pain.12

Other oral agents reported to improve symptoms include aspirin, ticlopidine, antihistamines, and prostaglandins.12 Even though nifedipine and verapamil have been reported as triggers for Erythromelalgia, their effect on vascular tone and blood flow makes them useful in the symptomatic management of the disease.9,15 Many authors regard aspirin as a reasonable first-line treatment due to its low side effect profile and early studies reporting its efficacy for dyscrasia-associated erythromelalgia.12,16 NSAIDs and opioids have been reported to provide minimal relief and are not recommended for the management of erythromelalgia.12 In addition to oral pharmacotherapy, topical preparations of amitriptyline-ketamine, lidocaine, capsaicin, and midodrine have been reported to reduce pain, with minimal adverse effects associated with their administration.12,17 Finally, intensive pain rehabilitation was shown to significantly improve both physical and emotional outcomes.12,18 A proposed algorithm based on these guidelines is provided in Figure 2, with dosages presented as reported in the literature.12,13,15–17 In addition, Table 1 provides an overview of the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Erythromelalgia has a profound impact on quality of life. The persistent, severe, and progressive nature of the pain, in conjunction with its frequent exacerbations, impairs physical, psychological, and social functioning, resulting in higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared to the general population. Local complications due to chronic cold exposure are common, including maceration, ulceration, hypothermia, and frostbite, often resulting in soft tissue infections and digital amputations.1,7,8,11,12,19,20

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

Corresponding author

Nikolai Bayro Jablonski, MD

9500 Euclid Avenue,

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio 44195

Email: BAYROJN@ccf.org