Background

Malaria is an infection that is a common febrile illness caused by the intraerythrocytic protozoan parasites of the Plasmodium genus which is transmitted by infected female Anopheles mosquito. Severe malaria by definition includes one or more of the following criteria: high burden of parasitemia of P. falciparum (>5% for non-immune patients and >10% for all patients), impaired consciousness, seizures, shock, pulmonary edema of acute respiratory distress syndrome, acidosis, acute kidney injury, abnormal bleeding or disseminated intravascular coagulation, jaundice, or severe anemia (Hb<7 g/dL).1 The majority of cases seen in the U.S are in people who have traveled to endemic areas, including Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Pacific Islands, South America, and Central America.2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2020 there were an estimated 241 million cases and 627,000 deaths globally due to malaria.3 In the United States (U.S.), there are an estimated 2,000 cases of malaria per year with about 300 people experiencing severe disease.4 About 5-10 deaths annually are reported according to the CDC.4

Malaria often presents with non-specific symptoms including fevers, chills, headaches, and myalgias. The diagnosis can easily be missed if providers are without context of these symptoms, including travel or residence in disease-endemic areas. The presentation can vary depending on the infecting species and the degree of parasitemia. Prompt treatment and diagnosis can be lifesaving as severe malaria can have fatal consequences.5,6 The recommended treatment for severe malaria is intravenous (IV) artesunate with weight-based dosing, administered at the time of presentation, 12 hours and 24 hours. Testing, while not required, can be of use to confirm disease if uncertain; however, confirmatory results should not prohibit prompt treatment of suspected malaria.1 The two most common malaria treatments available in the United States include atovaquone-proguanil and artemether-lumefantrine. If IV artesunate is unavailable, treatment may be initiated with second line agents while actively pursuing prompt procurement of IV artesunate.1,7,8

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man in New Orleans with no medical history was brought in by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) after being found unresponsive in his vehicle in a bank parking lot with the car running. Initial assessment revealed agonal breathing with a Glasgow coma scale of 3, necessitating a nasopharyngeal airway. Initial vitals included blood pressure 170/110, heart rate 114, respiration 34, and oxygen saturation 80%. Improved oxygenation to 86% was noted following an exchange of orotracheal airway. Once the patient was identified, it was then known that he had recently traveled to areas of Central and Northern Africa. The patient presented to an urgent care with 2-3 days of high-grade fever of 103-104 F, malaise, nausea and vomiting, soon after returning to the United States. He was prompted to seek immediate care with primary care for further testing, as malaria was very likely. Two hours prior to the presentation, he was directed to report to the emergency department by the triage nurse at his primary care clinic for immediate attention.

Initial examination was noticeable for small blanchable petechiae on the extremities and trunk. Laboratory data included leucocyte count 34,000, platelet count 14,000, elevated lactate dehydrogenase at 350, low haptoglobin at 10, with hypoglycemia at 58 (Table 1). Non contrast computed tomography (CT) of the head showed diffuse cerebral edema with effacement of sulci and gyri (Figure 1). The patient received two liters of normal saline, 250 mL of hypertonic (3%) saline, and intravenous ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and doxycycline. Within 2 hours of presentation, the patient’s hemodynamics became labile necessitating vasopressors, and the patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit.

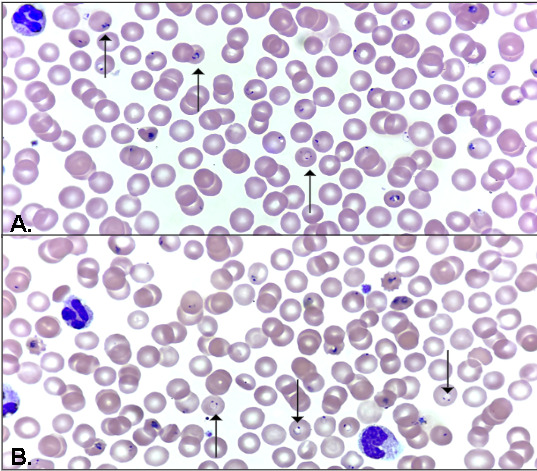

Malaria antigen PCR resulted positive for Plasmodium falciparum and the thin blood smear showed more than 500,000 parasites/mcL or 10% parasitemia (Figure 2). The infectious diseases team was consulted while simultaneously attempting procurement of IV artesunate. Due to its unavailability in the hospital, aggressive measures were undertaken to obtain IV artesunate as quickly as possible, which included phone calls to the CDC designated helpline, regional distributors, and local hospitals. One challenge for acquiring IV artesunate was that a Category 2 Hurricane was approaching the city within 24 hours. The patient was started on Artemether-Lumefantrine 80mg/480 mg PT and primaquine 30 mg PT via nasogastric tube given his comatose state.

His ICU course was notable for worsening hemodynamic instability with increasing vasopressor requirements complicated with multiorgan failure, severe metabolic acidosis, acute renal failure. Within 6-8 hours of admission, the patient had lost all reflexes including cough, gag, pupils, and corneal with absence of spontaneous breathing as seen on the ventilator. His family was updated on his rapidly declining status, and comfort measures were pursued.

Discussion

This case underscores the critical importance of early recognition and prompt treatment of severe malaria, including cerebral malaria. It also highlights the urgent need for more readily available parenteral artesunate in the United States. It illustrates how various levels of the healthcare system—ranging from initial point-of-care providers to national drug distribution protocols—must be aligned to prevent fatal outcomes. Timely access to life-saving treatments like artesunate should be a standard, not an exception.

Firstly, in terms of prevention, all individuals traveling to malaria-endemic regions should be educated on the importance of malaria prophylaxis. These medications are readily available, and with the aid of CDC guidelines, they are relatively simple to prescribe. Prophylaxis involves taking medication before, during, and after traveling to endemic areas, and the specific regimen should be tailored based on the region and the presence of chloroquine-resistant malaria strains. In this case, the patient had not taken prophylaxis prior to his travel. In the primary care setting, it is essential to consistently provide education regarding malaria risks and the benefits of prophylaxis. There is also a common misconception among patients who are originally born in endemic areas who have then developed partial immunity and then moved away that their immunity persists; however, over time their immunity wanes and prophylaxis is needed. Proactive engagement by primary care providers can help mitigate preventable cases of severe and potentially fatal malaria.1

Prompt recognition of malaria is also critical and can be lifesaving. In the United States there remains a significant gap in awareness among both patients and healthcare providers. Increased education is needed for recognizing symptoms of malaria and the urgency of seeking appropriate care. We recommend that travelers returning from malaria-endemic regions who present with febrile illness be promptly referred to a hospital system or emergency departments from their initial point of contact, as they are better equipped to initiate treatment, provide rapid diagnosis and supportive care. Streamlining this referral process may reduce delays in treatment and improve patient outcomes. Treatment should then be initiated promptly in all cases with a high suspicion of malaria even if testing with parasitemia has not yet been detected. In this case, aside from his travel history, highly suspicious features included fever, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminases.

We also suggest that hospital pharmacies maintain an on-site stock of parenteral artesunate, as time is critical in the treatment of severe malaria. Importantly, laboratory confirmation should not be a prerequisite for initiating treatment in suspected severe malaria. Laboratory confirmation should be used to continue treatment but not to initiate potentially time-sensitive life-saving medications. According to CDC guidelines, empiric treatment is warranted when there is high suspicion, and laboratory testing is delayed or unavailable. In this case, the patient presented with typical symptoms/signs of malaria, after returning from an endemic region, with a known history of no prophylaxis. Although testing was recommended during his acute care visit, it could not be completed in a timely manner.9

Prompt diagnosis and treatment is mandated when malaria is considered in the differential diagnosis, as it can progress rapidly to severe disease. In such cases, diagnostic tests of thin and thick smears versus polymerase chain reaction derived tests should not be prioritized. Our patient was quickly identified as having severe malaria. Shortly following admission, the patient had a positive rapid PCR test and blood smear was identified as P. falciparum.10 Other differentials that were considered are depicted in a tabular form (Table 2). These included meningitis/encephalitis, acute HIV, Leptospirosis, status epilepticus, acute stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Although severe malaria is rarely encountered in the United States, impaired consciousness and coma as typical manifestations of cerebral malaria are potentially reversible with initiation of therapy and rapid reduction in parasitemia. Treatment of malaria as per WHO and CDC, depends on severity, species identification and drug susceptibility (Tables 3 and 4).8,11 In patients with Plasmodium falciparum malaria, parasitemia levels above 5% in nonimmune individuals and 10% in immune individuals are classified as severe malaria. For those who are being treated with oral options, if prophylaxis was taken, those options should not also be used in treatment unless no other options are available.8 In the United States, the CDC recommends utilizing the CDC Malaria hotline to assist with treatment decisions if needed. For a specific population of patients, IV quinine may be considered in addition to initial treatment options, including those with travel history to areas of known Artemisinin resistance.

This case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion in all cases of fevers after recent travel. Treatment should be started promptly in all suspected cases as in this case: fevers, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and the absence of schistocytes in the peripheral smear, even before parasites are detected. This case also demonstrates the importance of having parenteral artesunate more readily available in the United States for the treatment of reversible cerebral malaria.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all those who contributed to editing and providing expert information pertaining to this report, including Coralia Castillo, MD (Tulane Pulmonary and Critical Care), Himmat Grewal, MD (Tulane Pulmonary and Critical Care), Gordon Love, MD (LSU Department of Pathology), Ayesha Younus, MBBS (LSU Department of Pathology).

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

Corresponding Author

Sarah Grace Lebovitz Perry, MD

Internal Medicine Resident

Tulane School of Medicine

New Orleans, LA

Email: sperry6@tulane.edu

_level_of_lateral_ventricle.png)

_level_of_lateral_ventricle.png)