Background

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease is a rare autoimmune condition that primarily affects the kidneys and lungs. It is characterized by rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) and pulmonary hemorrhage due to antibodies targeting the alpha-3 chain of type IV collagen in basement membranes. Diagnosis is confirmed through detection of circulating anti-GBM antibodies and renal biopsy findings showing linear IgG deposits. While anti-GBM disease typically presents with renal and respiratory symptoms, some patients exhibit dual positivity with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), which may confer a distinct clinical course and higher relapse risk.1,2 We report a case of dual-positive anti-GBM and ANCA-associated vasculitis, underscoring the importance of recognizing this overlap to help guide treatment decisions and long-term management.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old female with a past medical history significant for hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the emergency department with abnormal outpatient laboratory results, notably an elevated creatinine level of 8.96 mg/dL (normal 0.50-1.10 mg/dL), compared to her normal baseline. Vital signs were notable for blood pressure 163/71 mmHg, pulse 49 bpm, temperature 97°F, respiratory rate 27, and SpO₂ 97% on room air. The physical exam was benign; the patient was in no acute distress, not ill-appearing, and alert and oriented to person, place, and time without observed focal neurological deficits. Pulmonary effort was normal, and the abdomen was soft, non-tender, without guarding or rebound. Her home medications included lisinopril, baclofen, famotidine, gabapentin, umeclidinium, latanoprost, and nystatin. Initial labs showed a CK of 301 U/L (normal 30-135 U/L), and renal ultrasound revealed normal-sized kidneys (right 13.0 cm, left 13.4 cm) with normal contour, cortical thickness, and echogenicity; no stones or hydronephrosis were seen. Urinalysis was positive for 3+ blood, >500 protein, leukocyte esterase 2+, many bacteria, 31 RBCs, and 20 WBCs, but the patient had no UTI symptoms and urine culture was negative; antibiotics were discontinued after one dose due to low suspicion of infection. The patient was subsequently admitted to the medicine service for further evaluation. She denied any symptoms.

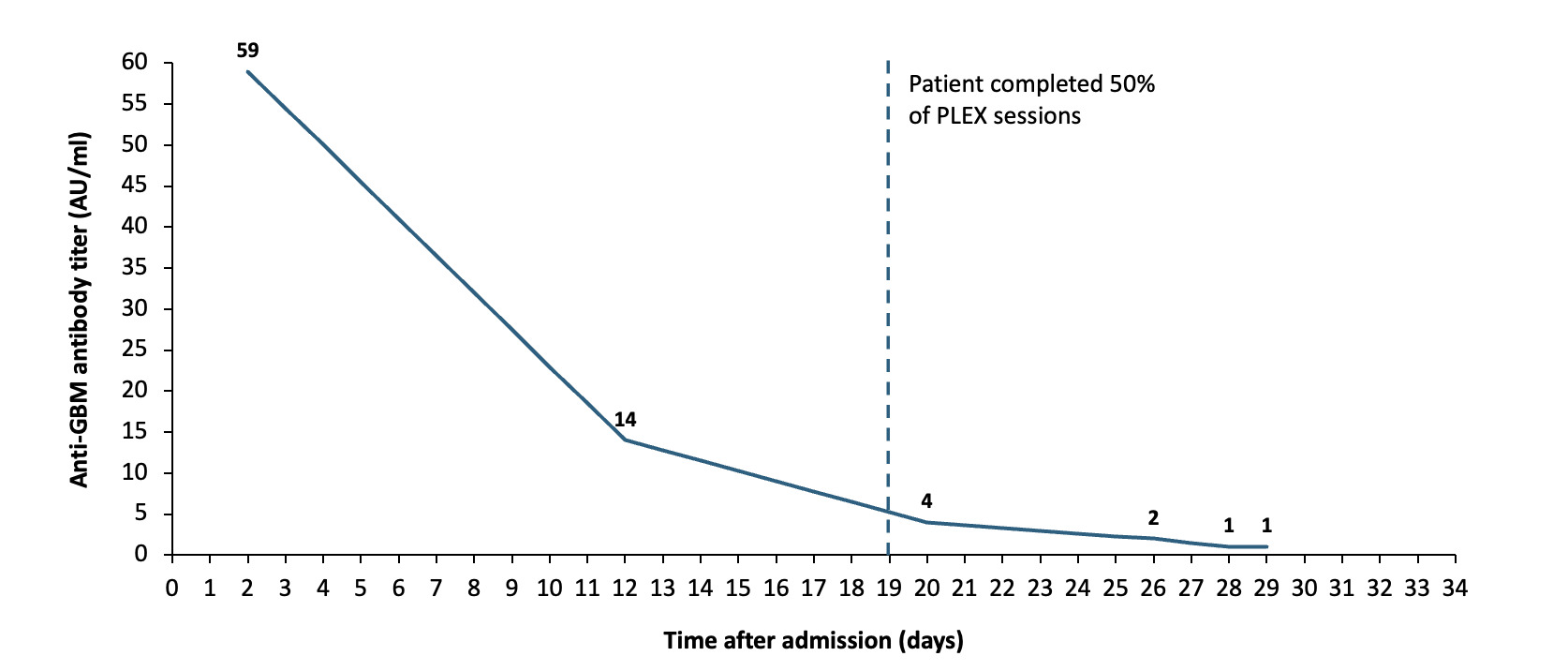

The nephrology team was consulted, leading to the detection of reactive ANA, positive p-ANCA, anti-MPO, and anti-GBM antibodies (MPO titer was elevated at 168 AU/ml and anti-GBM elevated at 59). Renal pathology showed crescentic injury in 63% of glomeruli with weak glomerular basement membrane staining, consistent with anti-GBM antibodies; the predominance of cellular to fibrocellular crescents suggested a pauci-immune process associated with ANCAs (Figure 1). Given these findings, the care team concluded a likely diagnosis of RPGN with positive serological markers. The patient received a steroid pulse with solumedrol 1 g daily for 3 days, then transitioned to prednisone 60 mg daily. Cyclophosphamide 75 mg PO daily and plasmapheresis (PLEX) were also initiated as separate therapies. Her first PLEX session was conducted shortly after renal biopsy, following successful placement of a permanent catheter. Hemodialysis (HD) was initiated the following day due to worsening hyponatremia, declining renal function, and changes in mental status. The patient followed a schedule of alternating PLEX and HD treatments throughout her inpatient stay.

During her hospitalization, the patient developed a left subcapsular kidney hematoma, detected through imaging after a drop in hemoglobin levels. She was transferred to the intermediate care unit for closer monitoring and received multiple blood transfusions. A subsequent CT scan confirmed the presence of the left-sided hematoma, which was managed conservatively, following consultation with the interventional radiology and surgery teams. Approximately one week after the initiation of PLEX and HD, the patient was found to have a central line infection caused by Enterococcus faecalis bacteremia, necessitating the removal of the Permacath and initiation of vancomycin therapy. Further complications arose with the development of an acute occlusive deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in the left proximal internal jugular vein, for which anticoagulation therapy was started. Despite these complications, there were no respiratory symptoms throughout her admission, including cough, dyspnea, chest pain, or hemoptysis and oxygen saturation levels remained at normal values. As the hospital course progressed, the patient’s management focused on the ongoing treatment of anti-GBM disease. Serial anti-GBM antibody levels were closely monitored, showing a marked decline from an initial elevated level of 59 AU/mL (normal <20 AU/mL), indicative of a positive therapeutic response. The last anti-GBM antibody titer showed a level of 1 AU/mL, a value that is generally considered negative or non-detectable (Figure 2). Anti-MPO antibodies were initially elevated at 168 AU/mL (normal <20 AU/mL) and decreased to 31 AU/mL four weeks later.

Following her final anti-GBM antibody titer, the patient completed her last scheduled PLEX session. Shortly before discharge, she had her final inpatient HD session and then transitioned to outpatient HD. The patient was discharged in stable condition, with plans for continued steroids, cyclophosphamide, anticoagulation with apixaban, and ongoing vancomycin therapy, as coordinated by the renal and infectious disease teams. Close outpatient follow-up was arranged to monitor her renal function, hematologic status, and infection risk. At her 4-week follow-up, renal function had not recovered, and she continued to require hemodialysis. She planned to transition to peritoneal dialysis and had established care with a new nephrology team. She was no longer on cyclophosphamide or prednisone.

Discussion

Anti-GBM disease is a rare autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies targeting the non-collagenous (NC1) domain of type IV collagen, a key structural component of the glomerular and alveolar basement membranes.2 Diagnosis relies on detecting circulating anti-GBM antibodies, typically via ELISA, and confirming with renal biopsy, which classically shows linear IgG deposition along the glomerular basement membrane. In patients with or without ANCA, anti-GBM antibodies target the same regions of type IV collagen (particularly the alpha-3 chain), suggesting a shared immunologic trigger regardless of ANCA status.3 Anti-GBM disease occurs in <1 case per million per year, with peak incidence in the third and sixth-seventh decades. Younger patients more often present with pulmonary-renal syndrome and have a slight male predominance, while older patients typically have isolated renal involvement and are more likely to be dual-positive for ANCA and anti-GBM.1,4,5 The exact cause remains unclear, but environmental exposures such as smoking, infections, hydrocarbon exposure, and certain medications have been implicated.6 No specific trigger was identified in this patient. In this case, the presence of anti-GBM antibodies, along with positive p-ANCA and anti-MPO antibodies, strongly supported the diagnosis. The renal biopsy confirmed crescentic glomerulonephritis with significant interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, findings consistent with advanced disease.

This case is notable for the coexistence of anti-GBM and anti-MPO antibodies. While either marker can be present in isolation, the combination suggests a transitional or overlapping autoimmune process, potentially blending features of both anti-GBM disease and ANCA-associated vasculitis. Such dual-positive cases may carry unique prognostic and therapeutic implications. Emerging data suggest that this subgroup may exhibit a biphasic disease course (initially anti-GBM-like with acute, often severe renal injury, followed by a more ANCA-associated relapse pattern) raising questions about optimal duration and intensity of immunosuppression. Current literature suggests that double-positive patients may have a more indolent disease course but a higher risk of relapses.1,4,7,8 Although double-positive patients share features of both diseases, the anti-GBM component typically drives more severe renal injury and a poorer prognosis, with limited likelihood of recovery from advanced renal failure. Early serologic testing for both antibodies and prompt renal biopsy are essential in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis to ensure accurate diagnosis and guide timely treatment.7,8

Standard treatment includes PLEX to rapidly remove circulating antibodies, combined with high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide to suppress further autoantibody production and inflammation.1,2 The patient’s treatment course mirrored standard anti-GBM protocols with PLEX, high-dose steroids, and cyclophosphamide. Maintenance immunosuppressive agents (i.e., rituximab) were also considered due to the dual positivity and relapse risk; prolonged immunosuppression may help prevent relapses driven by persistent ANCA-mediated autoimmunity.9,10 After nephrology consultation, the decision was made to withhold additional agents in our patient and monitor closely instead. However, complications such as the patient’s subcapsular kidney hematoma, central line infection, and DVT highlight the challenges of managing severe anti-GBM and its treatment-related risks. The hematoma, though rare, is a recognized complication in patients with severe renal disease and anticoagulation therapy, necessitating careful risk-benefit assessment. The central line infection highlights the susceptibility of these patients to opportunistic infections, emphasizing the importance of infection prophylaxis and prompt intervention in suspected sepsis. Ultimately, despite requiring hemodialysis, the patient’s disease stabilized, underscoring the potential for disease control with aggressive therapy. Although dialysis dependence remains a significant outcome for many patients with advanced renal involvement, timely intervention can mitigate further systemic damage and improve long-term quality of life.11

This case highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in managing anti-GBM disease, particularly in double-positive cases and those with significant treatment-related complications. The absence of pulmonary involvement reinforces the need to consider anti-GBM disease even in isolated renal presentations. Additionally, this case raises important considerations regarding long-term management, including the potential need for maintenance immunosuppression in double-positive patients, strategies for infection prevention, and approaches to mitigating treatment-related complications. Further research is warranted to refine treatment strategies, improve risk stratification, and minimize therapy-associated morbidity while optimizing patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this manuscript would like to thank Dr. Anthony Chang, Director of University of Chicago MedLabs, for providing the images of the patient’s kidney biopsy.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that there are no acknowledgements, conflicts of interest nor funding to disclose.

Corresponding author

Wilson Guo

Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

222 Richmond St, Providence, RI 029

Email: wilson_guo@brown.edu

_cellular_crescent_ob.png)

_cellular_crescent_ob.png)