Background

Babesiosis is an intra-erythrocytic, zoonotic protozoan infection endemic to the Northeastern United States. The clinical presentation varies partly due to common co-infections with other tick-borne illnesses, ranging from asymptomatic to fulminant sepsis, especially in immunocompromised patients. Splenic infarction is an increasingly reported complication of this disease; this case series aims to evaluate optimal treatment for Babesia microti-induced splenic infarct. Presently, there is a paucity of data regarding the management of atraumatic splenic infarction secondary to Babesia species (spp.) infections. At the same time, anticoagulation is a common treatment for most etiologies of splenic infarction. Patients with Babesia spp.-induced splenic infarction are at significantly greater risk of bleeding due to thrombocytopenia, making the role of anticoagulation less clear. This case series discusses three patients with babesiosis complicated by splenic infarction. We discuss the various situations in which the benefits of therapeutic anticoagulation to prevent further microthrombi and necrosis may outweigh the risk of significant bleeding.

Case Series

Case 1

A 72-year-old man with atrial fibrillation treated with systemic anticoagulation (apixaban), congestive heart failure with preserved ejection fraction New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class 1, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with radiation presented with five days of abdominal pain, fatigue, nausea, cola-colored urine, and decreased oral intake. He reported tick exposure at his home and work over the previous month.

Upon presentation, temperature was 36.7°C, heart rate was 74 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure 112/59 mmHg, and oxygen saturation was 96% on ambient air. On exam, he was ill-appearing. He was alert and oriented to self, place, time, and situation. There were scattered 1–4-centimeter ecchymoses throughout, as well as an eschar with surrounding erythema on the left upper extremity. Abdomen was tender in the epigastric and left upper quadrant region without rebound, guarding, or organomegaly. The rest of his examination was normal.

Laboratory analysis was pertinent for hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dL (normal,13.5-16.0 g/dL), platelet count of 34,000 /mm3 (normal,150-400 x109 plt/mm3), lactate dehydrogenase of 344 IU/L (normal, 100-220 IU/L), a d-dimer of 672 ng/mL (normal, 0-300 ng/ml), and haptoglobin of <8 mg/dL (normal, 40-268 mg/dL). Urinalysis was positive for 2+ blood and 2+ urobilinogen, but no casts. Blood parasite smear was positive for intraerythrocytic ring form parasites consistent with Babesia microti (Figure 1) and he was started on azithromycin and atovaquone for ten days. Doxycycline was also administered for empiric coverage of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis, which was discontinued once these serologies were confirmed to be negative. Initial parasitemia level was 1.06%. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast revealed a small wedge-shaped area within the spleen, consistent with a splenic infarct (Figure 2). Though no echocardiogram was performed to formally confirm the absence of infective endocarditis or cardiac emboli, there was high clinical suspicion that this infarct was caused by Babesia microti infection. It is important to note that this patient developed a splenic infarct while taking apixaban. Although novel oral anticoagulants are effective at decreasing the risk of recurrence of venous thromboembolism, they do not completely eliminate the risk. In the presence of a transient risk factor, such as an increased inflammatory state associated with infection, patients may develop “breakthrough” thrombosis, as the temporary hypercoagulable state outweighs the protective effects of anticoagulation therapy.1 His clinical status improved following treatment with azithromycin, atovaquone, and doxycycline. Anticoagulation with apixaban was continued throughout the hospitalization. A repeat blood smear two weeks after discharge showed an undetectable parasitemia level.

Case 2

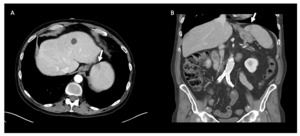

A 75-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and trigeminal neuralgia presented to urgent care with generalized fatigue, myalgias, subjective fevers, and worsening neuralgia for one week following a golf outing. Peripheral smear revealed a parasitemia level of 8% with a subset of altered, mature red blood cells infected by 1-4 (“tetrad”) small ring parasites consistent with Babesia microti infection. He was started on atovaquone, azithromycin, and empiric doxycycline coverage. His parasitemia level trended from 8% to 16.85% despite receiving this regimen for three days, thus he was switched to quinine and clindamycin and was transferred to a tertiary care hospital for possible exchange transfusion. His platelets continued to fall to 20,000/mm3 and his hemoglobin declined to 10.5 g/dL. A CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with IV contrast revealed a wedge-shaped splenic hypodensity consistent with infarct (Figure 3). Echocardiogram was not suggestive of infective endocarditis or cardiac emboli as the source of infarction. Exchange transfusion was deferred in favor of transitioning his therapy from quinine and clindamycin to atovaquone and azithromycin. He was also treated with doxycycline for presumed anaplasmosis during this time.

His parasitemia level downtrended to 1.15% with this regimen, however he developed acute respiratory failure due to non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. He was treated with intravenous furosemide. On hospital day five, he was transitioned to oral azithromycin and atovaquone. His platelet count recovered and stabilized at 150,000/mm3. He was started on therapeutic anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin for his splenic infarct. After an 18 day stay between two hospitals, his parasitemia level was undetectable and he was discharged to a skilled nursing facility on azithromycin and atovaquone. Based on the absence of evidence for other etiologies for splenic infarct, including cardioembolic source and malignancy, this patient’s infarct was treated as a provoked thromboembolic event with three months of therapeutic anticoagulation with apixaban.

Case 3

An 82-year-old man with COPD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, GERD, prior alcohol use disorder with withdrawal seizures, and depression who presented to his primary care physician with 4 days of abdominal pain, anorexia, and general malaise. He denied any recent tick bites, but lives on a large, wooded property where he spends much of his time. On presentation, he had a temperature of 38.2oC, blood pressure 111/59 mmHg, an irregular heart rate of 119 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 30 breaths/minute with an oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. On physical exam, he was ill-appearing and tachycardic, with decreased breath sounds and wheezing. His abdomen was diffusely tender to palpation without guarding or rebound, his skin was jaundiced, and a petechial rash extending from shins to feet bilaterally.

Laboratory analysis was notable for an AST of 95 IU/L and ALT of 74 IU/L, a white blood cell count of 2.5x 109/L (normal, 4.2-10.0 x 109), hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, and a platelet count of 23,000 plt/mm3. His respiratory pathogen panel and urine legionella were negative. Peripheral blood smear was positive for intraerythrocytic ring form parasites, with an initial parasitemia level of 0.81%. CT abdomen pelvis with IV contrast demonstrated multiple splenic infarcts and trace perisplenic fluid (Figure 4). These infarcts were attributed to babesiosis infection, though no echocardiogram was performed to formally confirm absence of infectious endocarditis or cardiac emboli. He was started on atovaquone and azithromycin to treat Babesia microti and was empirically treated with doxycycline for other tick-borne diseases including anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme Disease. He was also started on piperacillin-tazobactam to cover for other occult infection sources in the setting of severe sepsis. Anticoagulation was not recommended for his multiple splenic infarcts due to thrombocytopenia. Due to an abrupt change in mental status, a CT brain without IV contrast was performed and revealed a 6 mm right-sided subdural hematoma. A repeat CT brain without IV contrast 6 hours later confirmed the stability of this hematoma, and he was transfused one dose of platelets in the setting of an intracranial hemorrhage.

On hospital day 4, no parasites were seen on blood smear, but he remained in the hospital for four additional days due to worsening delirium. He was discharged on a 28-day course of atovaquone and azithromycin and a 21-day course of doxycycline.

Discussion

Babesiosis is an illness caused by intraerythrocytic protozoa, most commonly B. microti, which is endemic to the northeastern United States (RI, MA, NH, VT, ME, CT, NJ, NY), Minnesota, and Wisconsin.2–4 In 2020, a total of 1,827 cases of babesiosis were reported to the CDC, 98% of which were reported from individuals residing in these states.2 While B. microti is the focus of this case series, other Babesia species do exist, including B. divergens, more commonly seen in Europe, and B. duncani, reported in Washington and California.5–8 Babesia species are transmitted by the Ixodes scapularis tick, via blood transfusion, or via vertical transmission from an infected mother during pregnancy or delivery, though the latter two modes of transmission are far less common.9,10

The clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic in up to 20% of adults to end-organ dysfunction, including pulmonary edema, renal failure, atraumatic splenic rupture, and death.3,11 Those most commonly affected by severe infection include individuals over the age of 50, those with immunocompromised conditions, or asplenic patients.12 Most patients present with malaise, headache, fever, fatigue, and left upper quadrant abdominal pain, particularly in patients whose course has been complicated by splenic infarction.3,4,13,14 Common laboratory findings include non-autoimmune hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.2–4,11,14

Babesiosis is diagnosed by thin blood smear microscopy and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is more sensitive than peripheral blood smear and is particularly useful in cases with low-level parasitemia. Babesia parasites are nearly indistinguishable from malaria on the peripheral blood smear, with both inclusion bodies resembling “over-the-ear headphones”.15 The pathognomonic feature for Babesia spp. on a thin smear is the appearance of merozoites in tetrad formation, resembling the “Maltese Cross”.11 However, this feature is not easily visualized on peripheral smears and should not be relied upon as the only distinguishing feature. RBCs infected with malaria are more uniform in size and shape and are larger (average RBC surface area of 159.0 ± 15.2μm) than those infected with Babesia species (average RBC surface area of 140.2 ± 17.1 μm).16,17 Additionally, RBCs infected with Plasmodium spp. include a single inclusion body, whereas an RBC infected with Babesia spp. can include multiple inclusion bodies*.17*

Standard treatment for babesiosis includes atovaquone and azithromycin, or clindamycin and quinine. In the case of our second patient, all four were utilized due to the severity of disease The typical treatment duration is 7-10 days for mild to moderate infections in immunocompetent patients. However, in immunocompromised patients or in severe cases resulting in hospitalization, up to 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy may be required.18,19 According to the 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, these patients should receive intravenous antibiotic therapy until symptoms subside, then continue with oral therapy.19 Lyme disease concurrently infects between 25 and 67% of those infected with Babesia species therefore, doxycycline is often included to treat for Lyme disease empirically.20,21 In patients with high-grade parasitemia (>10%), severe anemia (<10 g/dL), or significant complications, RBC exchange transfusion may be considered in conjunction with antibiotic therapy.12

Occasionally, left upper quadrant pain due to splenic infarction is the lone presenting symptom. A systematic review of 34 patients with splenic complications—including splenomegaly, splenic infarct, and splenic rupture—reported that nearly half of patients with splenic complications had a parasitemia level < 1%, suggesting that the risk of splenic infarct is not related to the degree of parasitemia.13 Although infection has been identified as an independent risk factor for thrombosis (odds ratio of 11 for patients with systemic bloodstream infection compared to patients without infection), splenic infarct is a rare complication of babesiosis that has seldom been described in the literature.13,22 The current understanding of the pathophysiology is unclear and is based on studies of splenic complications in patients with malaria.3,4,12,14,23–25 Currently, there are two proposed mechanisms:

-

Lysis of RBCs by Babesia parasites releases vasoactive factors, which activate the coagulation system, promote microthrombus formation, and necrosis of splenic tissue, ultimately leading to splenic infarction.26,27 This mechanism is supported by a study by Wozniak et al., which demonstrated microthrombi formation in the smaller vessels of the spleen in hamsters inoculated with Babesia microti, resulting in coagulative necrosis.28

-

Similar to the mechanism proposed for patients with malaria who develop splenic infarcts—though rare—clusters of parasitized RBCs are unable to separate, causing RBC sequestration, obstruction of blood flow, and subsequent infarction of the affected area4,29,30

Splenic infarction secondary to thromboembolic events or autoimmune disease may benefit from therapeutic anticoagulation. However, there are no guidelines for the use of therapeutic anticoagulation in Babesia-induced splenic infarction.3,4,26,31–33 Management options include symptomatic treatment or splenectomy in the event of splenic rupture.4,12–14,24 Given our limited understanding of the pathophysiology, determining whether anticoagulation is appropriate is challenging. If these infarctions are the result of microthrombi formed from lysis of RBCs by babesia parasites, therapeutic anticoagulation may not be warranted. Studies investigating the utility of anticoagulation in disseminated intravascular coagulation secondary to sepsis—which parallels the described mechanism—are controversial In their systematic review, Zarychanski et al. suggest that anticoagulation may moderately decrease the likelihood of death compared to placebo without significantly increasing the risk of major hemorrhage.34 If, instead, the coagulation system is activated by an inflammatory response, anticoagulation may be beneficial to prevent further worsening of thrombosis. In this case, controlling the infection would limit thrombosis, thereby reducing the necessary duration of therapeutic anticoagulation. Finally, if the mechanism of splenic infarction is the result of sequestration due to cell clumping, as seen in sickle cell disease, anticoagulation is not recommended.31

Imaging alone cannot determine which of these mechanisms is involved. Therefore, unless a large vessel occlusion is identified — where anticoagulation is clearly warranted — the decision to anticoagulate should be based on a careful assessment of disease- and patient-specific factors, as reflected in the varied treatment approaches seen in this case series. When therapeutic anticoagulation is deemed appropriate, it may be advantageous to treat splenic infarcts with limited duration anticoagulation limited to 3 to 6 months.35 In non-cirrhotic patients who do not show evidence of active bleeding, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis recommends full therapeutic dose of DOACs. If DOACs are contraindicated, low-molecular-weight heparin or Vitamin K antagonists with an INR between 2.0 and 3.0 are suggested.35 Platelet count and evidence of bleeding should be closely monitored during this time.

Conclusion

Babesiosis is an illness endemic to the northeastern United States that most commonly presents with malaise, fever, and fatigue and is managed with either atovaquone and azithromycin, or clindamycin and quinine. In the cases described here, patients also presented with splenic infarct, a rare yet increasingly reported complication of babesiosis. While splenic infarctions of other etiologies are typically managed with anticoagulation, there are currently no guidelines regarding the use of anticoagulation in Babesia spp.-induced splenic infarctions, as the underlying mechanism remains unknown. Thus, the decision to treat Babesia spp.-induced splenic infarcts as provoked venous thromboembolic events should be weighed against the risk factors for bleeding on a case-by-case basis. Further large-scale studies are necessary to examine the benefits of anticoagulation in this setting.

Corresponding Author

Kaetlyn Arant BA,

Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University,

Providence, RI, USA

Email: kaetlyn_arant@brown.edu

__consistent_with_b.png)

__consistent_with_b.png)