Background

Colonoscopy is generally a safe procedure, though rare complications such as perforation and bleeding can occur. These complications are more common during therapeutic colonoscopies than diagnostic ones. It is essential for endoscopists to recognize atypical presentations of these complications, as early detection significantly reduces morbidity and mortality. Perforations may result from mechanical trauma, barotrauma, or electrocautery injury and can be intraperitoneal, extraperitoneal, or a combination of both. The majority of cases involve intraperitoneal perforation. The incidence of iatrogenic colonscopic perforations is estimated to be 0.016-0.8 % for diagnostic colonoscopies and about 0.02-8% for therapeutic colonoscopies.1 Worldwide, to date, only 33 cases of extraperitoneal perforation and 22 cases of combined perforation have been described.2 Out of these reported cases, the cecum was described as the site of perforation.

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB) is a form of extrapulmonary TB that typically presents with symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, and altered bowel habits. It involves the peritoneum, intra-abdominal lymph nodes, visceral organs, and the gastrointestinal tract, with the ileocecal region and peritoneum being the most frequently affected sites. These infections can also result in complications such as obstruction, strictures, or perforation in the affected areas.3 We report a case of extraperitoneal colonic perforation clinically presenting as substantial surgical emphysema in the neck region with imaging features of concomitant intraperitoneal involvement, in a case of ileocecal tuberculosis following diagnostic colonoscopy.

Case Presentation

A 21-year-old woman underwent an outpatient colonoscopy due to a six-month history of colicky abdominal pain localized to the right iliac fossa, accompanied by evening fevers, fatigue, and significant weight loss. She had no prior history of endoscopic procedures or surgery, was not on any regular medications, and had no known comorbidities. Her family history was notable for pulmonary tuberculosis. Colonoscopy revealed loss of vascularity, erythema, edema with deep ulcers noted extending from the sigmoid to the ileum, deformed Bauhin’s valve, ulcerated valve lip, and pulled-up cecum. The rectum and anal verge were normal. The patient had mild epigastric pain at the time of cecal intubation, towards the end of the colonoscopy, as the procedure was done without sedation.

Due to her complaint of mild abdominal discomfort, an abdominal X-ray was ordered. Shortly afterward, she developed shortness of breath and progressive subcutaneous emphysema in the neckThere were no signs of stridor or cyanosis, and her vital signs were stable except for tachycardia. On abdominal examination, the abdomen was soft with normal bowel sounds. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated CRP of 25 mg/L (normal <1 mg/L), a raised total white blood cell count of 13,000/µL (normal 4,000–11,000/µL), low albumin, and hemoglobin at 10 g/dL (normal 11–15 g/dL). All other laboratory parameters were within normal limits, and HIV testing was negative. The abdominal plain radiograph in the anteroposterior (AP) view showed air lucencies centered in the right iliac fossa extending along the right psoas muscle, consistent with pneumo-retroperitoneum(Figure 1A). Clear demarcation of the right renal margin was also noted. Air lucencies further extended along the right suprarenal region and superiorly till the diaphragmatic undersurface in the midline. No air was noted under the bilateral hemidiaphragms, suggestive of the absence of significant intraperitoneal free air. Air was seen extending along the right lateral pre-peritoneal fat plane cranially as well. A plain radiograph of the chest PA view showed extensive soft tissue emphysema along the bilateral sternocleidomastoid muscles as evidenced by air lucencies within (Figure 1B). The soft tissue emphysema was noted to dissect along the fascial planes to involve other neck muscles as well. Pneumomediastinum was also present. A plain radiograph of the neck lateral view revealed the soft tissue emphysema involving the anterior and posterior neck muscles extending cranially to the skull base (Figure 1C).

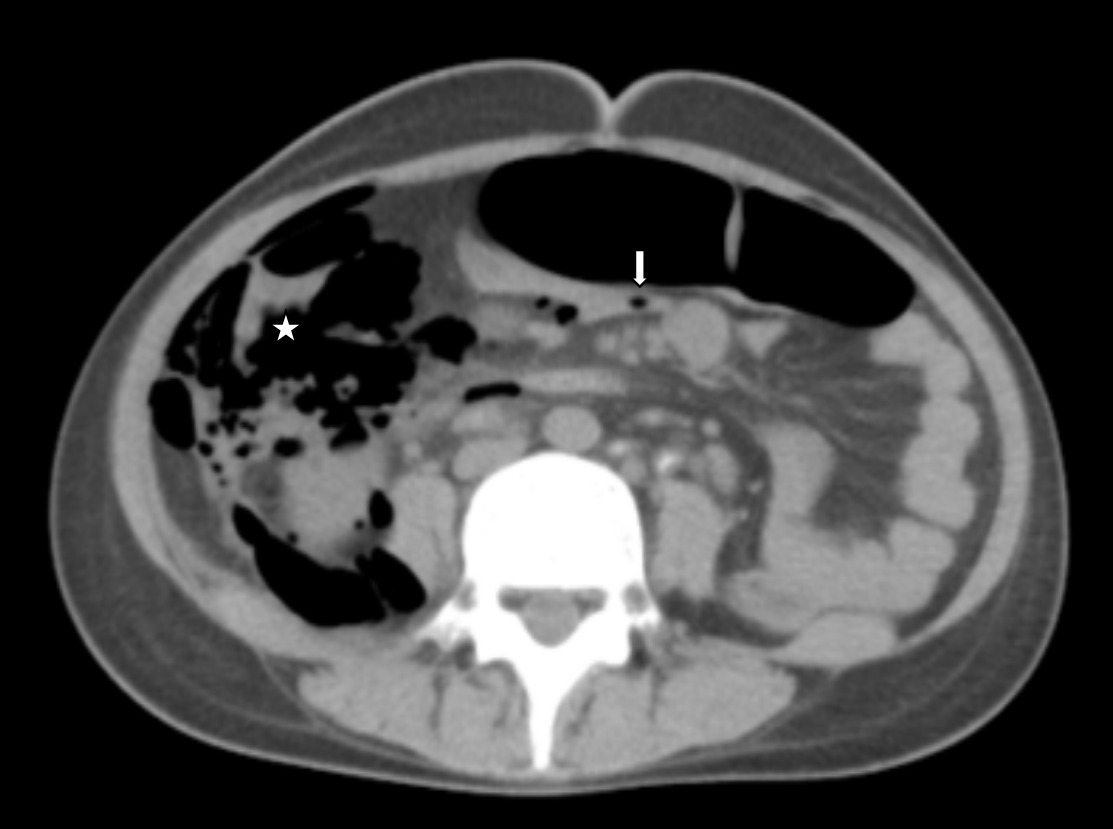

A plain computed tomography (CT) of the neck, thorax and abdomen was performed. CT axial cuts and soft tissue window of abdomen showed air pockets in the right iliac fossa in relation to the ileo-cecum with pneumo-retroperitoneum and intraperitoneal air in relation to the mesentery (Figure 2). However, air pockets were not present in the subdiaphragmatic region. There were multiple para-aortic and mesenteric lymph nodes, with a few showing calcifications. Pneumomediastinum, bilateral pneumothorax, and subfascial emphysema were also noted. No subdiaphragmatic air pockets were noted in this as well.

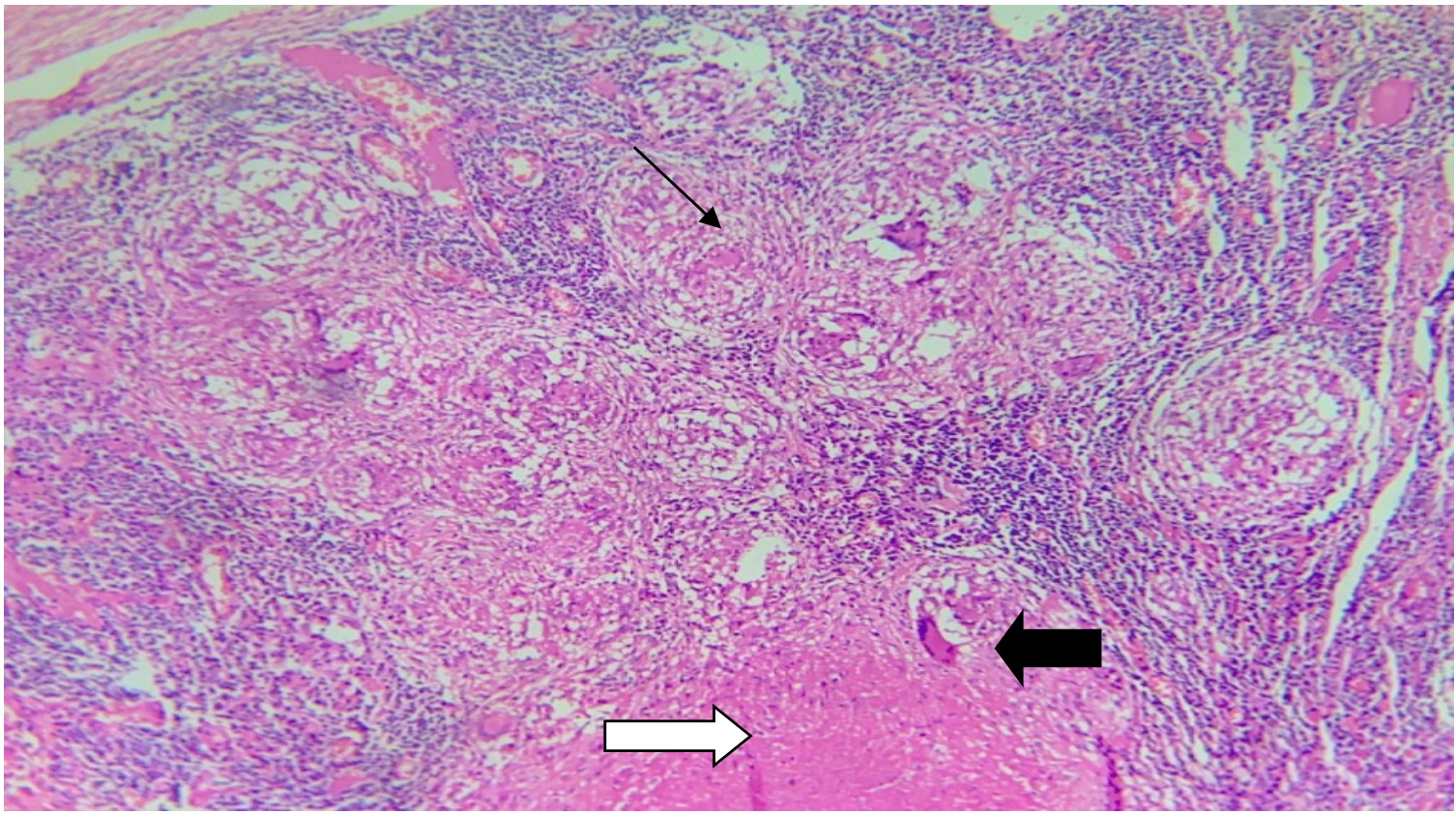

The patient underwent an emergency exploratory laparotomy after getting informed consent. A perforation of 2×1cm was identified on the retroperitoneal wall of the cecum. There were multiple caseating lymph nodes in the mesentery, hepatic flexure, and at 30cm from the IC junction. There was no evidence of peritonitis. A right hemicolectomy and primary anastomosis without a covering ileostomy were performed. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period. Histopathology reports of the right hemicolectomy specimen showed a chronic granulomatous lesion with caseation (Figure 3) involving the entire wall thickness, with multiple ulcerations and perforation involving the distal margin, ileocecal junction, and omentum. 27/30 lymph nodes had evidence of caseating granulomatous lymphadenitis with Langhans giant cells. Based upon the post-resection specimen biopsy findings, a diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis was made. She was discharged after initiating anti-tuberculosis treatment and is presently asymptomatic after 6 months of follow-up.

Discussion

Abdominal tuberculosis represents approximately 1-3% of all tuberculosis cases globally. Risk factors include HIV infection, female gender, immunosuppressive therapy, end-stage renal disease, and cirrhosis. The disease can involve various sites such as the oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, small and large intestines, rectum, anal canal, as well as visceral organs like the liver, gallbladder, spleen, and peritoneum. Primary abdominal TB can result from the ingestion of sputum from an active pulmonary TB patient or raw milk containing Mycobacterium bovis. Secondary TB spreads via direct, lymphatic, or hematogenous pathways from the lungs. The terminal ileum and the ileocecal region are the abdominal sites most commonly affected due to the presence of abundant lymphatic tissue (Peyer’s patches) that can take up bacilli, a narrow lumen, increased stasis of intestinal contents, and a high absorptive surface.3 The ulcerative type is the most common form of presentation, as seen in our patient. However, it may also present as hypertrophic, ulcero-hypertrophic, and fibrous stricture forms.4 The most common complication seen with abdominal TB is obstruction.5 However, perforation is associated with significantly higher morbidity and mortality in these patients.5,6 Other complications include upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding,7 fistula, malnutrition, malabsorption, and weight loss.3

Colonoscopy is a safe procedure that is presently widely used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Major complications following colonoscopy include perforation and bleeding. Colonoscopic perforations can be classified as intraperitoneal, extraperitoneal, or combined. The most common site of iatrogenic colonic perforation is the sigmoid colon, and thus intraperitoneal perforations outnumber other types.8 The existence of diverticula, acute angulation, and frequent looping of the scope makes the sigmoid the most vulnerable site.9 According to Laplace’s law, the pressure required to stretch the wall of a hollow tube is inversely proportional to its radius. Thus, among colonic segments, the cecum with the largest diameter requires the least amount of pressure to distend it, increasing the risk of perforation.

Primary perforations due to abdominal TB are rare and account for only about 1-10% of abdominal cases.5 The most common site of perforation in abdominal TB is the terminal ileum10, probably due to the pressure necrosis that develops proximal to the strictures, followed by inflammation, ulceration, and fibrosis that weaken the ileocecal wall.10,11 Intra-peritoneal perforation usually manifests as peritonitis with abdominal pain, distension, and guarding. On the contrary, extraperitoneal perforation has a varied range of manifestations, from being asymptomatic to severe respiratory distress due to tension pneumothorax. In cases presenting as severe shortness of breath, the patient may have stridor, oxygen desaturation, or cyanosis, which may demand invasive ventilation. Another atypical manifestation is subfascial emphysema, which is commonly mistaken for subcutaneous emphysema. Subcutaneous emphysema can occur in the face, neck, chest wall, abdominal wall, and thighs,2 which may be identified from swelling and associated crepitus in those regions. These atypical manifestations occur due to air sweeping along the fascial planes and large vessels from the retroperitoneum, ultimately reaching the neck, pericardial, mediastinal, and extra-pleural space.12

Hamdani et al. identified female gender, low albumin, and low BMI as key risk factors—conditions present in our patient as well.13 Existing literature lists diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis as recognized risk factors for iatrogenic colonoscopic perforations; however, ileocecal tuberculosis has not been reported, likely due to a scarcity of case reports from developing countries where tuberculosis is more prevalent. Extrapertioneal perforations caused by colonoscopy are rarely documented, particularly when the perforation occurs at the cecum. An extensive review of recent literature revealed only 3 cases of post-colonoscopy retroperitoneal cecal perforation.

Major mechanisms attributable to colonoscopic perforations include mechanical trauma upon manipulation of the colonoscope or a result of some intervention, thermal injury, and barotrauma from imprudent air insufflation.14 Panteris et al. concluded that 23% of perforations may be identified at the time of endoscopy by visualization of extra-colonic structures. In comparison, 77% were identified post-procedure, in the following hours to days.15 There are case reports where delayed presentations as intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis, have been reported. Both gastroenterologists and emergency department staff need to recognize the atypical presentations of colonoscopic perforations, as delayed diagnosis can result in morbidity rates as high as 44% and mortality rates up to 25%.1 In our patient, there is primarily extraperitoneal involvement along with some intraperitoneal involvement, indicated by air pockets concentrated in the right iliac fossa. The rest of the peritoneum is likely unaffected, as shown by the absence of air beneath the diaphragm. This may be explained by the organ’s pre-peritoneal location.

Computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality of choice to diagnose abdominal TB, which may show thickening of the ileocecal valve and medial wall of the cecum, an exophytic mass around the ulcerated lumen or an inflammatory mass that extends into adjacent muscle. Crohn’s disease presents similarly to abdominal TB; however, mural stratification, vascular jejunization, and mesenteric fibrofatty proliferation on CT are only seen in Crohn’s disease. Other differential diagnoses to consider are malignant neoplasms such as cecal carcinoma (which rarely extends beyond the ileocecal valve) and lymphoma (seen with aneurysmal dilation of the intestinal lumen). Perforation due to the lesion is typically presented on CT as a large amount of free gas and fluid in the abdominal cavity.16Once the diagnosis of perforation is confirmed, the choice between surgical and non-operative management depends on the type of injury, the quality of the bowel preparation, the underlying colonic pathology, and the hemodynamic stability of the patient.15 Treatment options include conservative treatment, exploratory laparotomy with resection and primary anastomosis, primary repair of perforation with proximal diversion ileostomy or exteriorization of perforation as a stoma, followed by stoma reversal. Surgical management is preferred when the perforation site is large, when peritoneal contamination is present, or when concomitant colonic disease is also present. In the absence of significant intra-abdominal contamination, bowel resection and primary anastomosis can be done as in our case. Endoscopic clips and endoluminal suturing with tissue approximation devices are emerging techniques that could be used in the future to prevent leakage of bowel contents, thereby reducing the risk of sepsis.15

Conclusion

Physicians should be wary of overlooking abdominal discomfort in a post-colonoscopy patient. This case underscores the importance of early detection and timely surgical intervention when needed, as prompt recognition allowed for successful primary anastomosis and an uncomplicated postoperative recovery. Additionally, ileocecal tuberculosis should be recognized as a potential risk factor for iatrogenic colonoscopic perforation.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding Author

Deepu George Simon, MBBS

Department of Internal Medicine

Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

Email: deepugeorgesimon@gmail.com

_view_showed_air_lucencies_centred_.png)

_view_showed_air_lucencies_centred_.png)