Background

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a medium- and small-vessel necrotizing vasculitis that predominantly affects the upper and lower respiratory tracts, often leading to sinusitis and cavitary lung lesions. Similarly, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) frequently presents with cavitary lung lesions on thoracic imaging. Symptomatic and radiographic similarities due to their pulmonary involvement may make it difficult to differentiate these diseases clinically. We discuss a patient who presented to a quaternary care academic medical center after receiving three weeks of rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE) therapy for presumed TB infection prior to receiving the diagnosis of GPA.

Case Presentation

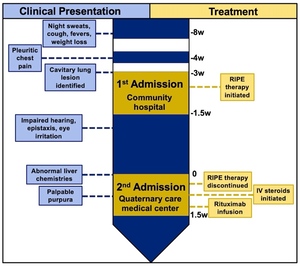

A 45-year-old male who recently immigrated from India with no known medical history presented with the chief complaint of worsening shortness of breath at rest (See clinical timeline: Figure 1). Two months prior to admission, he began experiencing night sweats and fevers with an associated 20-lb weight loss. One month later, he subsequently developed pleuritic chest pain and a worsening ulcerative lesion on his back that prompted him to present to a community hospital. A thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a 10 cm thick-walled cavitary lesion in the left lower lobe and a 6 cm right suprahilar mass initially concerning for potential infection versus malignancy. Given the patient’s recent immigration from a country where TB is endemic, and the presence of a cavitary lesion, he was empirically started on RIPE therapy. During the 12-day hospital course, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (MTB PCR) test was negative, two sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smears were negative, QuantiFERON gold was indeterminate, and AFB cultures and cytology from an endobronchial biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage were collected and processed. Despite negative testing, a high degree of suspicion for active TB remained, leading to the continuation of RIPE therapy at discharge with follow-up at the local health department. Ten days later, he was admitted for worsening respiratory symptoms and abnormal liver chemistries at the recommendation of the local health department.

Upon evaluation, he reported epistaxis, bilateral eye irritation, impaired hearing, and enlargement of his ulcerative back lesion. Initial urinalysis revealed proteinuria (46 mg/dL; ~800mg/day; protein/creatine ratio 0.84) and hematuria (55 RBCs/HPF), concerning for nephritis, with a normal serum creatinine (0.77 mg/dL) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (98 mL/min/1.73m2). A repeat thoracic CT scan re-demonstrated the cavitary lesions with an interval size increase (Figure 2). Nasal endoscopy demonstrated multiple nasal septal perforations, and otoscopic evaluation revealed bilateral tympanic membrane perforations. Following admission, the patient began experiencing burning bilateral foot and hand pain accompanied by evolving petechiae, which erupted two days later into erythematous and violaceous palpable purpura and vesicles (Figure 3A). Biopsy of purpura demonstrated findings consistent with small-vessel vasculitis (Figure 3B). Further examination revealed pink conjunctival lesions as well as white subretinal and choroidal lesions (Figure 3C) and strawberry gingivitis (Figure 3D). Biopsy of the ulcerative lesion demonstrated a mixed perivascular and interstitial mixed inflammatory infiltrate, potentially consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Subsequently, serum cytoplasmic-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (C-ANCA) tested positive (titer, 1:80), and serine proteinase-3 IgG (PR3-ANCA) was 546 AU/mL (ref<19 AU/mL). To confidently rule out concomitant TB infection, a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) yielded endobronchial biopsies of abnormal mucosa of the right lung (suprahilar mass) and a transbronchial biopsy of the left lower lobe cavitary lesion. The BAL sample produced a negative MTB PCR test and a negative acid-fast bacillus culture. Treatment was started with intravenous methylprednisolone and rituximab. The patient improved with treatment and was subsequently discharged with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

Cavitary lung lesions with accompanying respiratory symptoms offer a broad differential diagnosis, including etiologies with potentially competing therapeutics. Differentials often include malignant and infectious etiologies, including tuberculosis. However, in the proper clinical context, it is also important to consider less common etiologies, including autoimmune disorders. For a 45-year-old male who recently immigrated from India, a high initial suspicion for TB was reasonable from a symptomatic, radiographic, and epidemiologic standpoint, considering the high incidence of TB in India (27% of new cases worldwide in 2022)1 and that cavitary lung lesions occur in a majority of pulmonary TB cases. Further, in the United States, the incidence of TB is twice that of GPA (29 vs. 13 cases per one million people).2,3 However, the patient’s extrapulmonary symptoms, negative TB laboratory results, and worsening of symptoms on RIPE therapy raised suspicion for an alternative etiology.

Confirmation of GPA as the primary diagnosis and exclusion of concomitant TB is essential from a therapeutic standpoint in terms of reducing risks of adverse side effects from RIPE therapy as well as preventing further deterioration from untreated GPA. Before discovering the patient’s worsening clinical status upon initial presentation to the quaternary care academic medical center, it was suspected that the patient’s primary issues would be associated with the adverse side effects of RIPE therapy due to his abnormal liver chemistries. Rifampin, pyrazinamide, and isoniazid are known to cause hepatoxicity, and, specifically, isoniazid causes hepatoxicity in greater than 50% of patients within two months of treatment.4 Although his abnormal liver function tests were likely associated with RIPE therapy, this could not explain the other novel clinical findings. Moreover, before erupting into palpable purpura, his neuropathic-like pain in a stock-and-glove pattern could have been attributed to isoniazid therapy, which is also known to cause peripheral neuropathy and paresthesia. However, pyridoxine supplementation during treatment with isoniazid helps prevent this side effect, and these lesions were later biopsied and confirmed as a vasculitis. RIPE therapy causes various adverse side effects that are important to distinguish from disease progression, especially if that disease is incorrectly diagnosed.

Differentiating systemic illnesses with potentially overlapping features such as GPA and TB involves a multimodal diagnostic approach that can be both invasive and time-consuming. For a patient with prolonged constitutional symptoms and a cavitary lung lesion, a high pre-test probability for TB promotes an algorithmic methodology involving sputum AFB cultures/smears (sensitivity, 80%/45–80%) and MTB PCR (sensitivity, 70%).5–7 AFB cultures take several weeks for results on solid media, whereas AFB smears and MTB PCR results are largely facility-limited. For patients with negative sputum AFB smears and MTB PCR, subsequent TB testing occurs using BAL-derived samples which have increased sensitivity compared to testing of sputum and bronchial secretions.8 When symptoms are not fully explained by TB or if there is low pre-test probability for TB and GPA is considered in the differential, ANCA testing can be conducted in parallel, as it is often positive in patients with active disease. PR3-ANCA titers can then help differentiate GPA from non-ANCA-associated vasculitides (non-AAV). A titer of ≥ 65 AU/mL has been found to have an odds ratio of 34.2 in favor of AAV, which was easily met by our patient (546 AU/mL).9 In specific cases to confirm a GPA diagnosis, tissue biopsy is conducted for an affected organ (e.g., skin, kidney, upper respiratory/lungs), which would show evidence of a vasculitis or ill-formed granuloma with or without necrotizing features. In contrast, to help distinguish from GPA, TB results in granuloma formation with central necrosis and are typically well-formed. Specific to our case, histopathologic examination of transbronchial biopsies for patients with sputum-negative smears has an 87% sensitivity for TB,10 which showed evidence of ill-formed granulomas and did not comment on necrotizing features. Furthermore, although not required for diagnosis according to the American College of Rheumatology (and are typically nonspecific), ocular lesions (e.g., subretinal/choroidal lesions) manifest in approximately 50% of patients with GPA.11 Similarly, strawberry gingivitis is a rare, nonspecific clinical manifestation, but it may be the first manifestation of the disease.12 Although the tissue biopsy was nonconfirmatory, the comprehensive laboratory testing, imaging, purpura biopsy, and clinical context met the criteria for the classification of GPA by the American College of Rheumatology.13

While immunosuppressive therapy can lead to reactivation of latent TB, corticosteroids have been shown to improve outcomes in active pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB infections in specific clinical scenarios.14,15 For instance, in a meta-analysis, Critchley et al. (2014) found that corticosteroid use improved clinical outcomes of pulmonary TB at one month (risk ratio, 1.16) but did not reduce all-cause mortality; however, this finding was noted to be of low-grade evidence.14 In contrast, the other study found improved mortality outcomes for patients with pulmonary TB complicated by acute respiratory failure treated with adjunct corticosteroids (e.g., pulse steroid therapy).15 Besides the improved maintenance of airways through reduced inflammation, in vitro, dexamethasone is shown to abrogate TB-induced mitochondrial signaling that typically results in cell necrosis.16 Methylprednisolone, the gold-standard corticosteroid used to treat GPA, has a similar inherent mechanism of action as dexamethasone and would likely contribute to improved outcomes for patients with concomitant TB and GPA, as has been shown in another case report.17 Although much of the clinical evidence in favor of corticosteroid use for pulmonary TB is low-grade and specific to intensive care unit (ICU) settings, the absence of an unequivocal TB diagnosis warrants GPA treatment if there is concern for disease progression.

Clinical similarities between TB and GPA present challenging decisions in terms of treatment discontinuation and initiation, necessitating adequate laboratory, imaging, and pathologic workup to distinguish between the two diagnoses. Despite these similarities and the constellation of symptoms they represent, our case presented an additional epidemiologic factor that swayed the initial diagnosis and treatment of TB. When initially evaluated, this epidemiologic factor was likely a source of anchoring bias, emphasizing the need to start from a broad differential, especially since the patient’s initial TB tests yielded negative results. With adequate diagnostics – including c-ANCA positivity, dermatopathology showing vasculitis, interval progression of cavitary lung lesions on RIPE therapy, and a negative TB workup – we confidently diagnosed and initiated treatment for GPA. However, the patient may have benefited from earlier treatment intervention, as repeat TB testing was ongoing. Evidence, while low-grade, suggests corticosteroids are unlikely to harm patients with concomitant TB and may even benefit clinical outcomes.14,15 Future research should focus on assessing these clinical scenarios in non-ICU settings and advancing in vitro approaches16 to elucidate the benefits and determine the optimal timing for treatment initiation.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding author

Jonathon M Monroe B.Sc.

Medical Scientist Training Program,

Emory University School of Medicine

Atlanta, GA, USA

Email: jack.monroe@emory.edu

_right_upper_lo.jpeg)

_palpable_purpura_of_the_bilateral_lower_extremities._(b)_dermatopathology_of_left_lowe.jpeg)

_right_upper_lo.jpeg)

_palpable_purpura_of_the_bilateral_lower_extremities._(b)_dermatopathology_of_left_lowe.jpeg)