The frequent changes in payment for healthcare services and the complexity associated with keeping up with requirements are contributory factors to the many physician groups being absorbed by healthcare systems. The increased scrutiny from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other health management organizations (HMOs) regarding inpatient services, as well as a renewed emphasis on inpatient quality metrics and expanding penalties for all-cause readmissions, has given impetus to the pursuit of “forward” vertical integration by healthcare systems.1,2

The pursuit of integration by business entities is primarily driven by the need to achieve a larger market share and expand operations. Integration can be horizontal or vertical. Horizontal integration involves acquisitions or mergers with entities operating in the same industry, as in healthcare operations. Vertical integration involves acquiring or merging with other companies operating at various levels of the business supply chain. This strategy aims to gain control over an entire supply chain. There is “backward” vertical integration, which in the healthcare industry may occur in the form of an HMO acquisition by a healthcare system. The more common scenario, known as “forward” integration, involves the acquisition of physician practices by healthcare systems or HMOs.3

Both types of integration present significant challenges and are burdened by:

- Regulatory barriers

- Shifting market dynamics that limit the ability to meet established objectives

- Internal conflicts and tensions within the newly formed entities

Vertical integration seeks to lower costs and eliminate inefficiencies; however, it requires substantial investment in infrastructure, information systems, and human capital, making it an expensive undertaking. Currently, more than 58% of hospitalists are employed by healthcare systems. In the inpatient setting, hospitalists are increasingly interacting with newly acquired physician groups, including those in primary care, cardiology, orthopedics, and various other specialties. The alignment of goals between hospitals and hospitalist practices, carefully built over many years in the inpatient setting, is now often presumed to be easily transferable to these newly integrated groups, despite the complexities involved.4

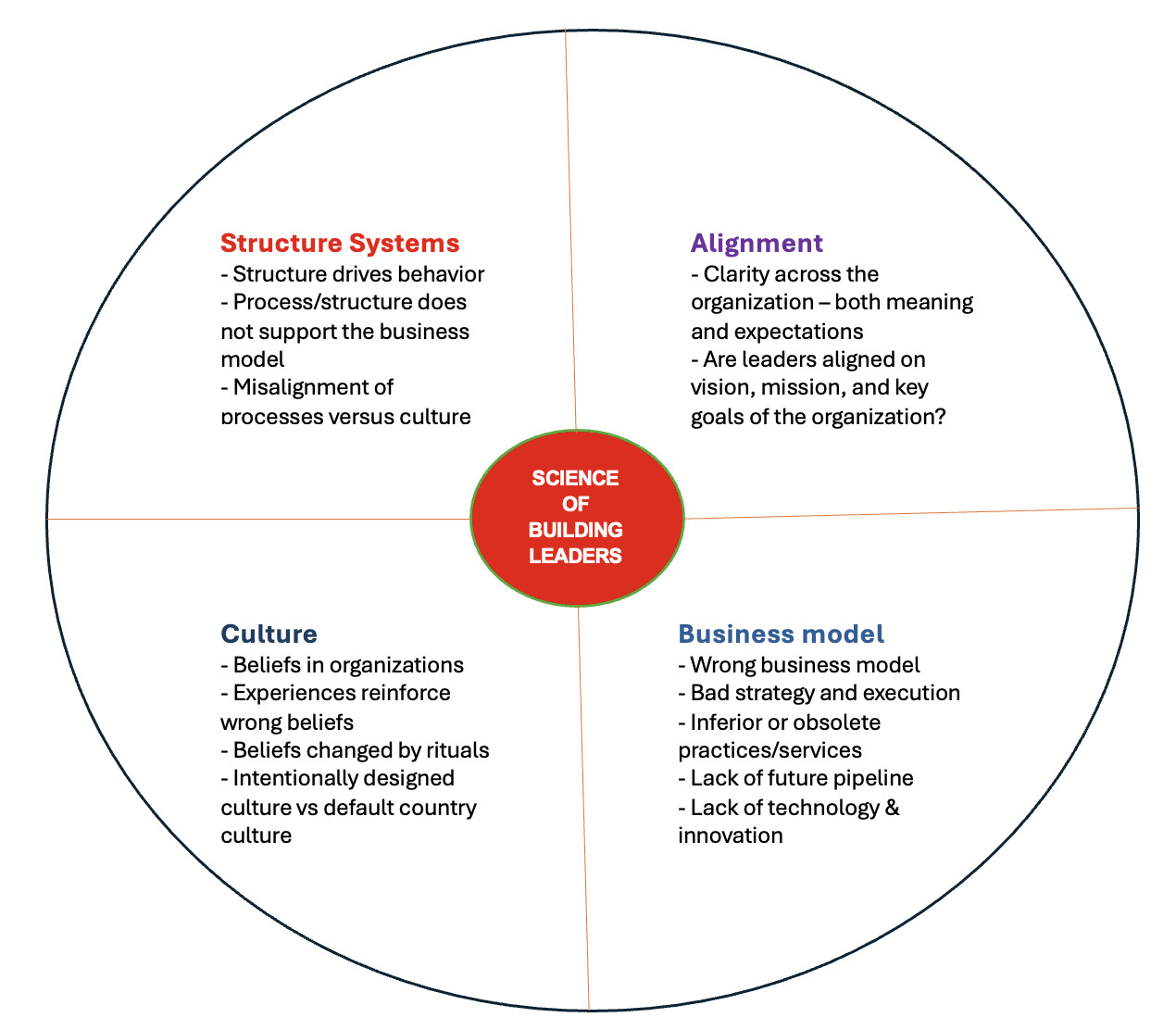

Alignment involves ensuring that an organization’s strategies, goals, and capabilities are in harmony with its core mission. For healthcare systems employing multi-specialty physician groups, establishing this alignment poses a significant challenge. Yet, it is essential for achieving shared objectives, enhancing performance, and creating a strategic fit. Conversely, a lack of alignment results in inefficiencies and undermines the ability to meet defined goals (Figure 1).4

Employment (E) does not necessarily guarantee Alignment (A).

The journey from E to A should address the following critical foundational/building blocks.

E------> D----->C----->B----->A

Successful integration within healthcare systems requires a deliberate, multi-faceted approach that balances operational efficiency with the preservation of core clinical, academic, and cultural values.

Development

To realize the objectives of integration, it is essential to preserve and strengthen the functional systems within the acquired entities. Beyond their clinical responsibilities, many physicians also engage in academic and community activities that are integral to their professional growth and personal fulfillment. Non-clinical roles, such as participation in voluntary educational efforts or providing care for uninsured populations, may require adaptation to align with the new organizational structure but should not be discarded. Furthermore, established clinical operations, including those in ambulatory surgical centers and laboratory services, warrant careful evaluation and thoughtful incorporation into the broader operational framework of the integrated system.5

By implication, legacy operational systems that diverge from the organization’s strategic objectives should be thoughtfully phased out or restructured. This process must be approached with deliberation and sensitivity to secure stakeholder engagement and support. Relevant examples include modifying the timing or allocation of specific functions, such as academic commitments or surgical operating room schedules. Achieving these transitions is aided by transparent information exchange and the presence of a shared governance framework, both of which are essential for fostering collaboration and alignment.5

Goal congruence

This necessitates a comprehensive understanding of core hospital operational principles, not only among leadership, but across all members of physician groups in order to foster mutually beneficial outcomes. Performance metrics that focus exclusively on individual productivity, such as relative value units (RVUs), may conflict with broader goals related to efficient patient flow and overall hospital performance in certain contexts.6

Culture

Every healthcare system possesses an inherent organizational culture that shapes its operational dynamics. The process of integration inevitably involves cultural convergence, which is often complex and demands both sensitivity and strategic acumen. As no single organizational culture is without limitations, there must be a deliberate commitment to embracing cultural adaptations that improve functionality—particularly within the inpatient setting and among newly integrated physician groups.7

Building strategic relationships

This represents one of the most complex yet ultimately rewarding aspects of integration, as it initiates the development of a foundation grounded in trust and mutual respect. It is essential for newly acquired physician groups to gain a thorough understanding of hospital operations and to actively participate in gain- or risk-sharing arrangements that foster deeper collaboration. Within academic institutions, aligning clinical and educational missions is of paramount importance. Academic programs and responsibilities must align with broader organizational objectives; however, the commitment to educating and training future clinicians remains a fundamental obligation. This core academic mission should be preserved, even as clinical operations evolve to meet changing system demands.6

Establishing clear guidelines is crucial for fostering synergy between inpatient and outpatient clinical operations. Operational excellence is achieved by identifying the optimal balance where the fundamental principles of patient experience and patient throughput are consistently integrated into daily practices and decision-making. Failure to maintain this balance can result in interpersonal conflicts, diminished quality of patient care, dissatisfaction among employed physicians, and, in some instances, the emergence of physician unionization efforts. The increasing presence of this third stakeholder, physician unions, adds a layer of complexity to the progression from integration to alignment.6

The quote by Winston Churchill, “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you can see,” is a profound statement that emphasizes the significance of learning from the past to shape a better future.8 In the context of hospital medicine, it is imperative to build upon and refine proven strategies for achieving alignment, especially as an increasing number of physician groups become integrated within healthcare systems. Such efforts are crucial for establishing a clear sense of purpose, facilitating effective collaboration, enhancing operational efficiency, and improving strategic adaptability.9

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

# Corresponding author

Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie, MD

Professor of Medicine, Clinical Educator

Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University

Division Director Division of Hospital Medicine

The Miriam Hospital, 164 Summit Avenue, Providence, RI 02906