Background

The question, “Would you bring your loved one for treatment at the hospital where you work?” effectively highlights healthcare professionals’ perspectives on patient care quality and experience within their institutions. A positive response underscores confidence in the clinical practices, safety measures, and patient-centered culture of the healthcare organization, emphasizing the importance of empathy and holistic patient experiences. Over the past two decades, patient experience has emerged as a foundational aspect of healthcare quality alongside safety and clinical outcomes. How patients experience their care affects more than personal satisfaction, as it influences adherence to treatment, trust in providers, and even clinical outcomes.1,2 A positive inpatient experience can mitigate fear, promote healing, and improve long-term health engagement.2,3 Hospitals now face increasing pressure to demonstrate excellence in patient-centered care, not just through treatment results but by how patients themselves feel about their care.

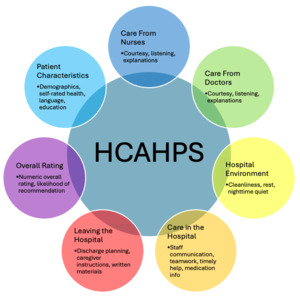

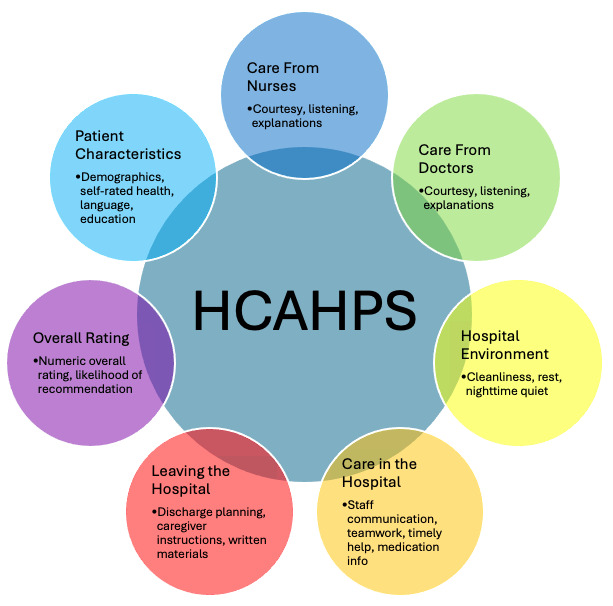

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) ties reimbursement to patient experience metrics such as those reported through the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey (Figure 1). Since 2012, CMS’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program has linked a portion of hospital reimbursement to HCAHPS scores, rewarding high performers and penalizing those that fall short.4 While the United States relies primarily on the HCAHPS survey, other countries have developed their own instruments to capture patient experience, often modeled after HCAHPS. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service Patient Survey Programme, overseen by the Care Quality Commission, gathers regular feedback in both inpatient and outpatient settings.5 Similarly, Japan (HCAHPS) and Canada (Canadian Patient Experience Survey) have their respective questionnaires, with Canada’s survey placing a greater emphasis on integrating cultural perspectives and including multilingual and Indigenous populations.6 While there are many similarities between the American survey and other surveys, perhaps the greatest difference is how they are used after being collected. In the US, HCAHPS is tied to reimbursement while in other countries, these surveys are used for quality improvement but do not include direct financial incentives. This is likely a reflection of the market-based private system in the United States which contrasts with nationalized healthcare systems. Patient experience describes everything from communication with physicians and responsiveness of staff to the cleanliness of the environment and clarity of discharge instructions. It reflects how patients perceive the care they receive, and not just whether it was clinically effective but whether it was delivered with clarity and empathy. The patient’s subjective experience is not only a good barometer for hospital performance, but perhaps it additionally should be treated as an end-in-itself. Ultimately, healthcare exists to serve our patients and enhance their lives.

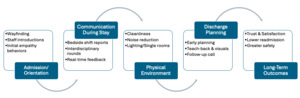

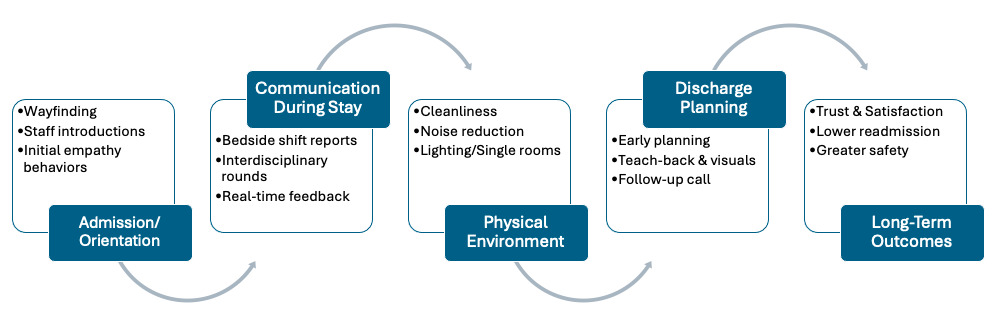

Patient experience is shaped by a series of interconnected moments that occur throughout a hospital stay, beginning long before clinical care is delivered and continuing through discharge. Each touchpoint, whether with front-line staff, the care team, or the physical environment, contributes to how patients interpret the quality, safety, and compassion of the care they receive. Understanding this journey helps hospitals identify opportunities to strengthen trust, improve communication, and create environments that support healing (Figure 2).

First Contact: Admission, Orientation & Trust-Building

A patient’s experience begins before the first clinical encounter, with the front desk, the directions, and the waiting room. First impressions can influence trust with the provider(s) involved, which is foundational to the subsequent inpatient experience. Respectful engagement from nonclinical staff, clear directions, and efficient intake procedures are common goals among hospitals today. For example, among non-English-speaking families in pediatric settings, early interactions have been shown to set the tone for the patient’s openness and emotional state throughout their stay.7 Hospitals that incorporate orientation into the intake process, such as explaining the daily schedule, introducing the care team, and offering a basic layout of the room, tend to achieve better HCAHPS outcomes, particularly in overall satisfaction and likelihood to recommend the hospital.4,8 When front-line staff are trained in empathy, eye contact, and clear communication, patients are more likely to feel safe and reassured.8,9 Nurses are often the first and most consistent caregivers that patients encounter, making them central to early hospital perceptions. Individualized nursing care, where nurses tailor interventions to each patient’s unique needs and values, significantly increases patient satisfaction by fostering trust.10 By contrast, poor early experiences, such as unclear directions, long wait times, or brusque interactions, can erode trust before a provider even enters the room. This kind of early dissatisfaction can influence the patient’s perception of subsequent care, making it more difficult to recover their confidence.11 Because these initial moments are simple to address yet profoundly influential, they represent a low-cost, high-impact opportunity to shape patient experience.

Communication Throughout the Stay

Once admitted, one of the most critical factors shaping the inpatient experience is communication. Communication plays a central role in shaping how patients evaluate their care, particularly because it is the most visible and personal element of the healthcare experience. This includes not only the exchange of information, but also non-verbal and emotional components such as tone, empathy, body language, and active listening, all of which have been shown to influence patient satisfaction and trust.9,12 One study from a large urban teaching hospital found that patients who did not receive a post-discharge phone call were more than twice as likely to rate physician communication below “top box” on the HCAHPS scale.13 When outcomes are less than ideal, patients who feel that they were informed, respected, and heard are more likely to express trust and gratitude.9 Given their sheer volume of time spent with patients, nursing communication especially stands out as one of the strongest predictors of overall satisfaction. Specifically, engaging patients themselves in nursing-led bedside shift reports strengthens the hospital-patient relationship.14 Other structured communication interventions, such as multidisciplinary rounds conducted with patients present and regular check-ins, have demonstrated measurable improvements in patient-reported satisfaction.15,16 The emotional tone of clinical interactions also matters. Studies show that patients interpret warmth, attentiveness, and eye contact as signs of both competence and compassion.9,17 This is especially critical in contexts where patients may feel vulnerable or disempowered, such as in mental health units or among children and adolescents. For example, one study of psychiatric inpatients found that patients who felt included in decisions about their care reported significantly higher satisfaction levels, even when the overall setting was restrictive.18 Another study in a pediatric setting found that open-ended questioning and consistent caregiver presence improved the child’s comfort and the parent’s trust in care teams.19 These subtle but meaningful acts of engagement help patients feel seen and respected, regardless of diagnosis. While some aspects of communication may come naturally, effective communication in clinical settings is a skill that can also be cultivated. Hospitals that invest in formal empathy and communication training for clinical staff often see improvements across multiple HCAHPS domains.20,21 To be sustainable, however, these efforts must be reinforced by leadership support and integrated into everyday practice.

The Role of the Physical Hospital Environment

The physical setting in which care is delivered has a powerful impact on patient experience, influencing both comfort and perceived quality of care. Patients consistently report that cleanliness, noise levels, room layout, and access to natural light influence their sense of safety, restfulness, and dignity during hospitalization.22,23 These environmental factors are often overlooked in clinical conversations but can significantly affect recovery, sleep, and emotional state. In psychiatric inpatient settings, patients report feeling more respected and secure in facilities with modern, uncluttered designs and access to private spaces.23 Studies have also found correlations between quieter hospital environments and higher satisfaction scores, especially in units where noise disrupts rest or communication.24 Similarly, natural lighting and windows with outside views have been associated with improved mood and reduced stress among general inpatients.25 Thoughtful design choices, including single-patient rooms, clearly marked directions, and comfortable seating for family members, have been shown to reduce anxiety and promote more positive evaluations of care.22,24 While environmental improvements can require financial investment, they represent a long-term strategy for enhancing experience that benefits both patients and staff.

Transition of Care During Discharge

The discharge process is an important moment in the inpatient experience. Even when clinical care has been excellent, a rushed discharge can leave patients feeling unprepared, anxious, or abandoned. Patients consistently rank clear instructions, medication reconciliation, and follow-up coordination as vital components of a positive transition home.3,26,27 Effective discharge communication is associated with better outcomes, including lower readmission rates and higher satisfaction scores.28,29 Discharge preparation is especially important for older adults and those with complex conditions, who often struggle with information overload and unclear instructions.27,30 Several studies suggest that involving patients and families in discharge planning early—sometimes even at the time of admission—can improve understanding and reduce preventable complications after leaving the hospital.3,27 Providing written summaries, visual aids, and direct phone numbers for follow-up questions empowers patients and supports a smoother recovery.26 One study found that patients who received structured post-discharge phone calls reported greater confidence in managing their care and were more likely to rate their overall hospital experience positively.29 Despite its importance, the discharge phase can vary widely in quality and consistency. Ensuring that patients leave with clarity and connection to ongoing care can greatly affect their final impression of the hospital and foster better long-term engagement.

Addressing Cultural Difference in Patient Experience

Patient experience is not uniform across populations. Studies have documented consistent differences in reported satisfaction by race, language, and socioeconomic status.31–33 These differences may be shaped by communication barriers, cultural misunderstandings, or varying expectations of care. Patients with limited English proficiency, for example, often report lower satisfaction with provider communication, even when interpreter services are available.7,33 Similarly, some patients report feeling less involved in decision-making or unsure about discharge instructions, which can impact both satisfaction and outcomes.^18, 27 ^ Hospitals have implemented a range of approaches to better meet the needs of diverse populations. These include improving interpreter access, offering written materials in multiple languages, and providing staff training in cross-cultural communication.7,34 One study found that culturally adapted discharge planning was associated with improved ratings in patient understanding and follow-up adherence.26 Shared decision-making (SDM) that systematically elicits patients’ cultural beliefs, language needs, and values—and employs interpreters, plain language, and teach-back—enhances perceived respect and involvement in care.35,36 By reducing decisional conflict and aligning care plans with patient priorities, SDM improves patient-experience domains such as clinician communication, shared understanding of the treatment plan, and discharge preparedness, particularly for culturally and linguistically diverse populations.35,36 Shared decision-making also mitigates power asymmetries by positioning patients as partners, strengthening trust and adherence.

Reimagining Patient Experience Measurement

Patient experience is a nationally recognized quality metric, incorporated into ratings by The Leapfrog Group and designated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as one of five primary domains in its overall “star rating.”36 While patient experience has become a standard quality domain, how it is measured often shapes how it is managed. Most hospitals rely on the HCAHPS survey, which provides important comparative data, but it is not without limitations. Patients often struggle to recall specific details weeks after discharge, and the multiple-choice format may limit nuance in their responses.37,38 As a result, many organizations focus on easily quantifiable elements, such as courtesy scripts or wait time reductions, without addressing deeper contributors to trust, communication, and emotional safety. Some facilities treat patient experience primarily as a compliance requirement rather than a core component of care quality.39–41 Alternative methods, such as real-time feedback tools, patient interviews, or narrative comments, may offer a richer view of what matters to patients.38–40 Involving patients directly in the design and evaluation of care processes, sometimes referred to as co-design, has also been shown to identify priorities that standard surveys overlook.37,42 Improving patient experience measurement does not require abandoning existing tools, but expanding beyond them. When hospitals focus more on understanding the full context of patient experience, they are better equipped to make meaningful improvements.

Conclusion

Improving patient experience extends beyond satisfaction to encompass safety, trust, and long-term engagement. From admission to discharge, patients’ impressions are shaped by communication, environment, inclusion, and preparedness. Lasting improvement requires sustained investment in communication training, co-design, culturally informed care, and responsive discharge planning. Patient experience is not just a metric—it reflects care delivery and a pathway to high-quality, patient-centered outcomes.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding Author

Farzana Hoque, MD, MRCP, FACP, FRCP

Associate Professor of Medicine

Department of Internal Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63104-1016 USA

Phone: 314-257-8222

Email: farzanahoquemd@gmail.com