Background

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare and potentially life-threatening disorder characterized by the sudden development of autoantibodies that inhibit coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) function or accelerate its clearance.1 The estimated incidence is approximately 1 to 1.5 cases per million individuals per year.2 Despite its rarity, AHA poses a significant clinical challenge due to its potential for severe bleeding complications, particularly when the diagnosis and treatment are delayed. The mortality rate can reach up to 41% in untreated cases.2,3 We describe a rare case of acquired hemophilia A associated with an unusual clinical condition, highlighting key diagnostic and therapeutic considerations.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old male merchant with a medical history of hyperuricemia, systemic arterial hypertension, and diabetes mellitus presented in September 2023 with swelling, pain, and fever in his right hand, consistent with a soft tissue infection as noted in Figure 1.

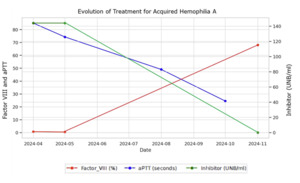

The patient reported no illnesses in the preceding three months, including arboviral infections, influenza, or COVID-19. He underwent prolonged antibiotic therapy with benzathine penicillin (1,200,000 IU intramuscularly), cephalexin (500 mg orally), and ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) for over 30 days, resulting in a slow but complete resolution of the lesions. Approximately two months after recovery, without other infections, he began experiencing extensive bruising and hematomas on his upper limbs and thighs following minimal trauma (Figure 2). He denied mucosal bleeding, such as epistaxis, gingival bleeding, hematuria, or hematochezia. During the infection, he experienced significant weight loss of approximately 20 kg, which stabilized and returned to baseline within 45 days of clinical improvement.

The patient was referred to the hematology service for evaluation of the bleeding symptoms. Initial laboratory tests revealed hemoglobin of 11.9 g/dL, leukocyte count of 7,500 cells/mm³ (78% segmented neutrophils, 20% lymphocytes), platelet count of 342,000 cells/mm³, creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL, and glucose of 148 mg/dL. Levels of alkaline phosphatase, serum calcium, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and gamma-GT were within normal ranges. He was also evaluated for systemic autoimmune diseases and all relevant laboratory tests were normal (antinuclear factor, rheumatoid factor, complement, anti-double-stranded DNA, serum protein electrophoresis). Malignancy was also ruled out based on clinical examination, laboratory tests, imaging and endoscopic procedures. He denied using medications such as clopidogrel, recurrent anti-inflammatory drugs, or other chronic medications typically linked to AHA.

Coagulation tests showed a prothrombin time (PT) activity of 89% and an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 85 seconds, with a ratio >1.5. Additional testing revealed normal von Willebrand factor activity and antigen levels, normal thrombin time and fibrinogen levels. The mixing study for aPTT indicated the presence of an inhibitor with an elevated circulating antibody index (30%), while factor VIII levels were markedly reduced (0.4%), and high inhibitor titers for factor VIII (144 Bethesda units) were detected. These findings confirmed a diagnosis of acquired hemophilia A in April 2024, possibly triggered by immune dysregulation following a recent infection and prolonged antibiotic therapy, after exclusion of autoimmune and neoplastic conditions.

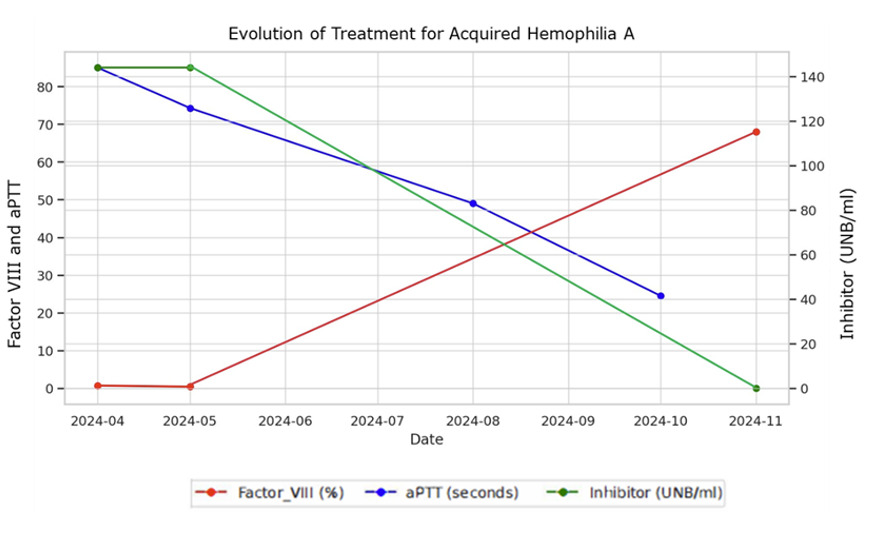

The patient was treated with immunosuppressive therapy, including cyclophosphamide (50-100 mg/day for 22 weeks) and prednisone (1 mg/kg for 24 weeks). During the early stages of treatment, the patient developed a large hematoma in his right upper limb. A bypassing agent (activated prothrombin complex concentrate, aPCC/CCPA) was prescribed but ultimately not administered, as the bleeding episode resolved spontaneously before infusion. Follow-up laboratory tests demonstrated progressive improvement, with a reduction in inhibitor levels and recovery of factor VIII activity, as shown in Graph 1. After 24 weeks of treatment, the patient had an undetectable FVIII inhibitor and an FVIII level of 68%, with all other coagulation tests within normal ranges. The patient’s coagulation profile is currently normal, and no complications have been observed during follow-up.

Discussion

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is an uncommon disorder that mainly occurs in people over 60 years of age and affects both sexes. However, notable cases have also been documented in individuals aged 20 to 30, most often in women after pregnancy.4 The etiology of AHA remains unidentified in approximately 50% of cases, while in the remaining cases, several provoking factors have been recognized, including autoimmune diseases, hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, dermatological disorders, pregnancy, drug reactions, and, more recently, COVID-192.In autoimmune diseases, AHA generally ranges from 13% to 17% and is associated with systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, Goodpasture’s syndrome, and dermatomyositis. It is also linked to high inhibitor titers, making treatment challenging.1,5 In the context of malignancies, cases are more commonly associated with solid tumors and may either precede the tumor diagnosis or manifest as a paraneoplastic syndrome.5

The present case describes AHA in a young patient (< 60 years old), likely associated with prolonged antibiotic therapy and soft tissue infection. Although infection-associated acquired hemophilia A (AHA) has been reported in various contexts, including soft tissue, pulmonary, and viral infections (including SARS-CoV-2), the pathophysiological mechanisms are thought to involve transient immune dysregulation and loss of tolerance to factor VIII.6 In our patient, the infectious episode was localized and clinically resolved before the onset of bleeding and laboratory abnormalities, making a direct infection-related mechanism less likely. However, it is plausible that infection-related immune activation, in combination with prolonged antibiotic exposure, may have contributed to the breakdown of immune tolerance and triggered inhibitor formation.6 Similar dual mechanisms, infectious and drug-related, have been proposed in previous case reports .2

Although evidence in the literature is limited regarding this association with antibiotics, some studies have examined it, particularly in relation to prolonged use of fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin, with cases occurring even weeks after the medication was discontinued.7,8 Although AHA developed after a prolonged antibiotic exposure, the timing by itself does not establish a causal relationship. Both the infection and the antibiotic treatment could have contributed to immune dysregulation and subsequent inhibitor formation, but their specific roles remain uncertain. Consequently, this association has not been established, and its pathophysiology, risk factors, and mechanisms are poorly understood.7,9 More broadly, several other drugs and antibiotics have been implicated as potential triggers of AHA, including penicillin and its derivatives, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, methyldopa, fluphenazine, clopidogrel, phenytoin, paclitaxel, fludarabine, interferons, and phenobarbital.10

The pathophysiology of drug induced AHA is largely unknown, though it is believed to be multifactorial. Proposed mechanisms include an exaggerated immune response leading to cross-reactive antibodies (IgA, IgM) that recognize FVIII epitopes, impairing its function, loss of immune tolerance, and interference with vitamin K metabolism.7,10 While the primary treatment is discontinuation of the suspected drug and supportive hemostatic therapy, prolonged immunosuppressive treatment is often required.11Unlike congenital hemophilia A, which is predominantly characterized by massive joint bleeding, AHA more commonly presents with spontaneous bleeding in the subcutaneous tissue, muscles, soft tissues, mucosa, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system, potentially leading to life-threatening hemorrhage.4 Consistent with the literature, the patient in this case mainly presented with bleeding in the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

In cases of spontaneous bleeding without a personal or family history of coagulation disorders or anticoagulant use, laboratory tests assessing coagulation function are recommended.12 The hallmark laboratory finding in AHA is an isolated prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) with a normal prothrombin time (PT).4,9,12 If isolated aPTT prolongation is observed without a history of anticoagulant use, further testing is warranted to differentiate factor deficiencies from the presence of specific inhibitors.13 The Bethesda assay is the gold-standard test for detecting coagulation factor inhibitors, with titers >5 BU/mL classified as high and <5 BU/mL as low.12 In the present case, initial laboratory investigations confirmed a markedly reduced FVIII activity on two consecutive measurements, prompting further evaluation for inhibitors. The Bethesda assay revealed a high inhibitor titer (144 BU), confirming the diagnosis of AHA. As per diagnostic criteria, AHA is defined by low FVIII activity and a high inhibitor titer,9 both of which were present in this case.

Following AHA confirmation, the primary treatment objectives are the prevention of hemorrhagic complications and inhibitor eradication, which should be initiated as early as possible.4,12,14 First-line therapy consists of prednisone (1 mg/kg/day), used alone when FVIII levels are ≥1 IU/dL and inhibitor titers ≤20 BU, with response rates ranging from 30% to 48%.2,15 In severe cases (FVIII <1 IU/dL or inhibitor >20 BU), prednisone is combined with cyclophosphamide (1.5–2.0 mg/kg/day) .13 Rituximab is reserved for refractory cases or when first-line therapies are contraindicated.4 In this case, given the severely reduced FVIII activity and high inhibitor titer, treatment was initiated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide, resulting in an excellent response without severe adverse effects. To control bleeding, bypassing agents are recommended in patients with active hemorrhage, with recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) and activated prothrombin complex concentrate (APCC) being first-line therapies, demonstrating an 80–90% efficacy rate in severe cases.4,12,13,15 Treatment should be maintained until hemostasis is achieved, with prolonged therapy in cases of intramuscular or intracranial bleeding to prevent recurrence.12 In this case, APCC (50 IU/kg) was indicated for use in the event of significant hemorrhage. Spontaneous inhibitor resolution occurs in approximately 33% of cases, typically in those with low inhibitor titers, but may take years to manifest.4 However, recurrence has been reported in 15–24% of cases, with a median relapse time of 3–4 months.15 Therefore, regular monitoring of FVIII activity and inhibitor levels is recommended: monthly for the first 6 months, every 2–3 months until 1 year, and semiannually thereafter.2 In this case, follow-up was conducted monthly for 6 months, with coagulation tests performed regularly, although specific FVIII and inhibitor assays were not consistently performed due to logistical constraints.

Conclusion

The rarity of acquired hemophilia A contributes to diagnostic delays, often resulting in late recognition of the condition. However, given the high risk of severe hemorrhagic complications, early diagnosis is crucial for the timely initiation of treatment, significantly improving prognosis and reducing mortality. In resource-limited settings where serial factor assays are not feasible, especially inhibitor screening and dosing with the modified Bethesda method, clinical follow-up and surveillance of basic coagulation parameters (aPTT, PT) remain a practical and effective approach. It is therefore essential for general practitioners to remain vigilant for this condition and to be familiar with its diagnostic approach and therapeutic management.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding author

Jandir Mendonça Nicacio MD, MSc, PhD

Professor, School of Medicine,

Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco -UNIVASF, Petrolina (PE), Brazil

Email: jandir.nicacio@univasf.edu.br