Background

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS), a condition characterized by recurrent nausea and vomiting due to chronic cannabis use. Cannabis use by itself is not a risk factor for WE; however, chronic consumption resulting in Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome can precipitate thiamine deficiency, resulting in WE. It is important to note that 8.4% of the US population are cannabis users, thus making this syndrome highly relevant in clinical practice.1 Thiamine (B1) is crucial for metabolism and energy and is sourced only from the diet.2 Severe deficiency can cause Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE), prevalent in 0.4%-2.8% of the population, with 50% linked to alcohol.2 Chronic alcohol consumption can disrupt the absorption of vitamin B1 (thiamine) in the intestinal tract, leading to alcohol-related Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Additional mechanisms contributing to thiamine deficiency in alcohol users include poor dietary intake, hepatic dysfunction reducing thiamine storage, and impaired phosphorylation of thiamine to its active form, thiamine pyrophosphate.2 However, non-alcohol related WE cases have been reported in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum, gastrointestinal and hematological cancers, bariatric surgery, malnutrition, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 Here, we discuss a case of Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome presenting with WE.

Case Presentation

A 28-year-old woman presented with persistent nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and a 10 kg weight loss over two months. She had two prior hospitalizations within the past year for similar symptoms with recurrent episodes of vomiting with unrevealing workup, including laboratory tests, abdominal computed tomography (CT), and upper endoscopy. Antiemetics offered minimal relief. She reported using cannabis daily for the past year, before which she used cannabis occasionally. She denied alcohol, other illicit substance use, or chronic health conditions. The diagnosis of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was presumptive, inferred from the temporal association between escalating cannabis use and recurrent vomiting, with resolution upon cessation, in the absence of a definitive diagnostic test.

Two weeks before her current hospitalization, she developed worsening double vision and, five days prior, complained of blind spots in both eyes. Her husband noted difficulty walking in a straight line, with frequent swaying. On assessment, she was hemodynamically stable with a BMI of 25 kg/m². She appeared confused and followed commands intermittently, with a Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) score positive for acute-onset inattention and disorganized thinking. Eye examination revealed esotropia with restricted abduction in both eyes, reduced visual acuity to light perception bilaterally, and normal retina and anterior chamber. Neurological examination showed an ataxic gait with an initial International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS) score of 48/100, indicating moderate ataxia. Limb strength was intact, reflexes were decreased, and sensory perception was preserved. Cranial nerve examination was normal, with no meningeal or spine involvement.

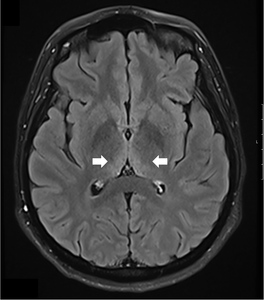

A comprehensive laboratory workup, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Lyme disease serology, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, and viral hepatitis panel, was negative. The urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and amphetamines. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated increased T2 signal intensity in the bilateral medial thalami with no involvement of the mamillary body (Figure 1). There was no evidence of optic neuritis, demyelinating lesions, meningeal enhancement, mass effect, or hemorrhage. MRI of the spine showed no active or chronic spinal cord lesions. Nerve conduction studies (NCS), along with serum testing for anti-ganglioside GM1 and anti-GQ1b antibodies, were normal. These tests were conducted to rule out atypical forms of demyelinating neuropathies in light of the patient’s hyporeflexia. Given the clinical presentation and imaging findings, a lumbar puncture (LP) was not performed, as there was no suspicion of infectious, demyelinating, or vascular pathology. The diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy was confirmed by a low whole blood thiamine level (7 nmol/L; reference range: 8–30 nmol/L), measured using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Quantitative assays of other vitamins (B12, folate, Vitamin A, D, E and K) were within normal limits.

The patient was started on high-dose intravenous thiamine therapy, following established guidelines for the management of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Based on recommendations from the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS), she received 500 mg of intravenous thiamine every 8 hours for 3 days to rapidly replenish thiamine stores and prevent further neurological deterioration. This was followed by a maintenance dose to support continued recovery and prevent relapse. As her symptoms improved, particularly nausea and abdominal discomfort, she was able to tolerate oral intake. Her diet was gradually advanced to a standard oral regimen as clinical stability was achieved. Repeat MRI brain showed resolution of thalamic hyperintensities at 3 months follow-up (Figure 2)

Discussion

Thiamine (B1) is a cofactor in essential enzymatic reactions for energy metabolism. Deficiency can lead to lactate buildup and increased glutamate production, resulting in excessive excitatory neurotransmission and potentially causing vasogenic and cytotoxic edema.1 Daily thiamine requirements range from 1 to 2 mg, absorbed in the jejunum and stored in the liver.4 The body stores about 30 mg of thiamine, and deficiency can occur within 2 to 4 weeks of inadequate intake, especially in the presence of chronic illnesses.5

Thiamine deficiency categories include reduced intake (malnutrition, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome), impaired absorption (Crohn’s disease), diminished storage (cirrhosis), and increased demand (refeeding syndrome, malignancies).6 Each category correlates with the development of WE through the lens of thiamine’s metabolic roles. For instance, malnutrition, persistent vomiting and reduced intake in CHS leads to decreased intake and nutrient loss, limiting coenzyme availability and predisposing to lactic acidosis and neurological dysfunction. This mechanism parallels hyperemesis gravidarum, in which persistent vomiting leads to ongoing nutrient loss, decreased intake, and increased metabolic demand, contributing to nutrient deficiency. Cirrhosis impairs hepatic thiamine storage, thereby reducing reserves during periods of metabolic stress. Refeeding syndrome and malignancy increase carbohydrate metabolism demands, exhausting thiamine stores rapidly and precipitating acute deficiency. These mechanisms explain why WE often presents during catabolic states or after sudden reintroduction of nutrition.

Wernicke’s encephalopathy prevalence varies: 1% in the general population, 8% post-bariatric surgery, 12.5% in alcoholics, and 20% in critically ill patients.7,8 The clinical manifestation of WE varies widely. While the classic triad of encephalopathy, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia occurs in only 15% of cases, especially in non-alcoholics, the most common feature is altered mental status, ranging from delirium to coma.6,9 According to the Caine criteria, the diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy can be made if two or more of the following are present: dietary deficiency, oculomotor abnormalities, cerebellar dysfunction, and altered mental status or mild memory impairment. In non-alcoholic patients like those with CHS or cancer, encephalopathy may occur in isolation. Ocular findings, such as horizontal nystagmus or abducens palsy, reflect brainstem involvement, while ataxia predominantly affecting the lower limbs results from cerebellar and vestibular dysfunction. Additional features like hypothermia, high-output cardiac failure, vomiting, and lactic acidosis can be traced back to thiamine’s central role in mitochondrial energy metabolism.1 The differential diagnosis for ophthalmoplegia and ataxia in non-alcoholic patients includes Miller Fisher variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, and mitochondrial disorders such as Leigh syndrome. These were excluded in our patient based on normal nerve conduction studies, negative antibodies, and the absence of demyelinating or mitochondrial features on MRI.

CT is usually non-specific but widely available, lacks sensitivity, and is primarily useful for excluding other intracranial pathologies such as stroke or mass lesions. MRI, with a sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 90%, reveals characteristic symmetrical hyperintensities in the mammillary bodies, medial thalami, and periaqueductal gray matter.6 Diagnosis of WE is further supported by biochemical testing. Erythrocyte transketolase activity, a functional marker of thiamine status, may be reduced in Wernicke’s encephalopathy and show improvement with thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) addition. However, its clinical use is limited by low sensitivity, moderate specificity, lack of standardization, and reflects intracellular thiamine function.9 Newer methods, such as whole-blood thiamine levels, are more reliable than plasma levels; the most sensitive test—liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of thiamine diphosphate (TDP)—remains under FDA review.10 Whole-blood thiamine was measured due to its accessibility and quick turnaround, though it is less accurate than erythrocyte transketolase activity or TPP levels in reflecting functional thiamine status. These preferred tests, though more reliable, are limited by availability and longer processing times.

Given the limited intestinal absorption during deficiency states and the urgency of neurologic deterioration, parenteral thiamine remains the cornerstone of treatment. High-dose intravenous thiamine, typically 500 mg three times daily for 2–3 days, then 200–500 mg daily for 5 days, is recommended, followed by oral maintenance therapy.5 Clinical response is variable but may include rapid improvement of ocular symptoms within hours and gradual resolution of ataxia and confusion over a week.1 Rome IV diagnostic criteria for CHS include prolonged and excessive cannabis use, recurrent episodes of nausea and vomiting, relief with hot bathing behavior, and resolution of symptoms after cessation of cannabis. CHS is often missed due to nonspecific symptoms and underreported cannabis use, with its paradoxical nature adding to diagnostic delay. Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) differs from cyclical vomiting syndrome by its association with chronic cannabis use, symptom relief with hot bathing behavior, and resolution following cannabis cessation, which were present in our patient. Few reports have been reported in the literature describing Wernicke’s encephalopathy associated with cannabis hyperemesis syndrome, highlighting the rarity of this presentation and the importance of clinician awareness.11,12 Understanding risk factors to identify Wernicke’s encephalopathy in non-alcoholic patients and initiate timely treatment.

Conclusion

Non-alcoholic Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is often underdiagnosed. In our patient, 8 weeks of persistent vomiting due to cannabis hyperemesis syndrome led to severe thiamine deficiency. The condition is frequently overlooked due to nonspecific symptoms, stigma associated with cannabis use, and absence of the classic triad. High clinical suspicion is essential, as early and aggressive thiamine replacement is critical to prevent irreversible neurological damage. Future research should focus on increasing clinician awareness, developing standardized diagnostic criteria for non-alcoholic WE, and exploring the pathophysiological mechanisms linking cannabis use to thiamine deficiency to improve early detection and outcomes in this population.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding author

Harshitha Chowdary Popuri, MD

Resident Physician

Department of Internal Medicine

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso,

4800 Alberta Ave, El Paso, TX 79905

Email: hpopuri@ttuhsc.edu