QUESTION 1: HOW SHOULD PATIENTS WITH VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM AND HIGH-RISK MEMBRANOUS NEPHROPATHY BE MANAGED?

A 53-year-old man with a remote history of hepatitis B infection and a recent diagnosis of membranous nephropathy was admitted with worsening anasarca and found to have a right lower-extremity deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). He has no family history of chronic kidney disease or hypercoagulable disorders and is taking losartan and bumetanide. On examination, he was afebrile, with a heart rate of 89/min and blood pressure of 124/54 mmHg and appeared non-pale and anicteric. He had periorbital edema without conjunctival injection, decreased air entry at the lung bases without wheezes or crackles, and a distended but soft, non-tender abdomen with a positive fluid wave and normal bowel sounds. Neurologically, he was alert with no focal deficits. His extremities demonstrated extensive bilateral edema, with tenderness and erythema over the right thigh and diminished right-sided pedal pulses, but no induration. Laboratory studies showed a normal CBC and renal function but significant hypoalbuminemia at 2.1 g/dL. At the time of his initial nephropathy diagnosis, his 24-hour urine protein was 7.5 g/day, his PLA2R antibody titer was 125 RU/mL, and hepatitis B serologies showed positive surface and core antibodies with negative antigens. He was transitioned from heparin to apixaban. What is the next step in his management?

A: This patient’s DVT occurred in the context of nephrotic-range proteinuria, which contributes to a hypercoagulable state through urinary losses of antithrombin III, protein S, and fibrinolytic factors such as plasminogen. Additionally, severe hypoalbuminemia stimulates hepatic production of various proteins, leading to elevated levels of procoagulants including fibrinogen, factor V, and factor VIII. Initial management of primary membranous nephropathy is generally conservative and involves loop diuretics for edema, renin–angiotensin system blockade to reduce proteinuria, and statin therapy for dyslipidemia, with approximately 30% of patients achieving spontaneous remission within two years.

In the presence of high-risk features for disease progression, the addition of immunosuppressive regimen is recommended. Delays in initiation of immunosuppressive therapy results in a much higher rate of progression to end stage renal disease (ESRD). High risk features in patients with membranous nephropathy include:

-

Acute kidney failure

-

DVT or renal vein thrombosis

-

Proteinuria >8000mg/day

-

PLA2R antibody levels> 100RU/ml

In light of his elevated PLA2R level and new DVT, timely nephrology consultation to assess for initiation of immunosuppression is warranted. Close monitoring of his renal function, serum albumin, proteinuria, and repeat PLA2R titers will be essential. Because up to half of patients with persistent nephrotic-range proteinuria ultimately progress to ESRD, timely escalation of therapy is critical. Available immunosuppressive options include steroid–cyclophosphamide regimens, rituximab, and calcineurin inhibitors.1

QUESTION 2: HOW SHOULD PATIENTS WITH A POSITIVE HEPATITIS B CORE ANTIBODY BE MANAGED PRIOR TO INITIATING IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE THERAPY?

A 45-year-old man recently diagnosed with ANCA-associated vasculitis is preparing to begin immunosuppressive therapy with Rituximab, Avacopan and prednisone. He has a prior history of hepatitis B, and his current serology shows a negative hepatitis B surface antigen, positive hepatitis B surface antibody, and positive hepatitis B core antibody. His gamma-interferon assay is negative. Does he require management of his hepatitis b in addition to his immunosuppressive therapy?

A: Chronic hepatitis B infection progresses through four phases: immune tolerant, immune active, immune control, and reactivation. Reactivation may occur spontaneously or be triggered by immunosuppressive therapy, particularly in individuals with resolved or chronic hepatitis B. Determining a patient’s phase of infection relies on interpreting hepatitis B e antigen and antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody, hepatitis B core antibody, ALT levels, and hepatitis B virus DNA (Figure 1).2

Treatment for chronic hepatitis B is indicated for individuals in the immune active phase and is also recommended for those in the immune control phase if cirrhosis is present, given the increased risk of decompensation with hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation. Immunosuppressive therapies, including those used in autoimmune, gastrointestinal, neurological, rheumatological, renal, and pulmonary conditions can precipitate hepatitis B reactivation. This risk applies not only to individuals with chronic hepatitis B who are surface-antigen positive but also to those with resolved infection who are surface-antigen negative but core-antibody positive. Reactivation is defined by rising HBV DNA and re-emergence of detectable surface antigen. Importantly, the presence of hepatitis B surface antibody does not exclude reactivation risk and should not be used by itself to determine whether antiviral prophylaxis is needed.2

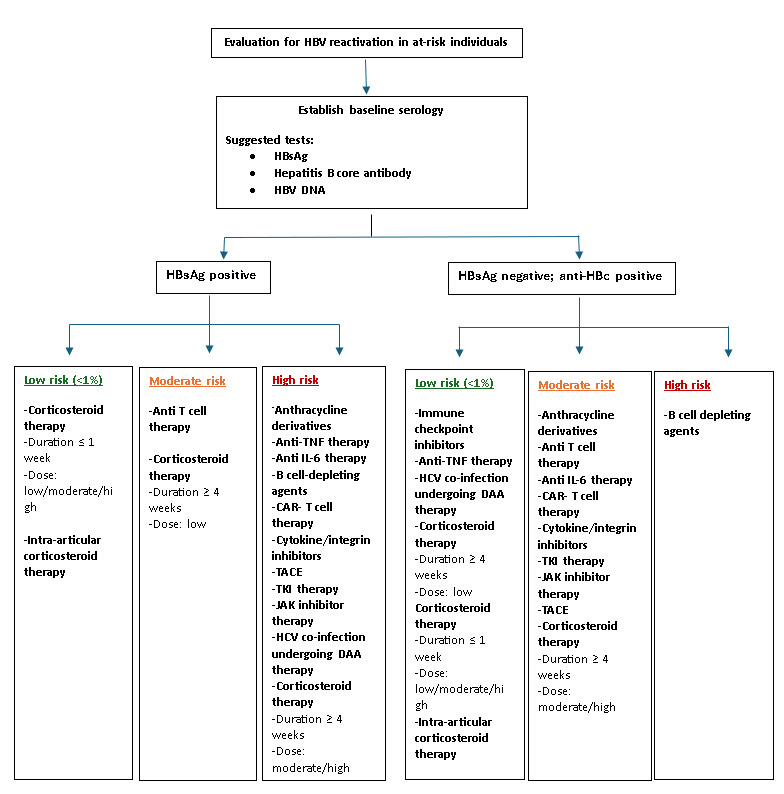

Risk-stratification guidelines recommend antiviral prophylaxis for individuals with a high (>10%) risk of reactivation, while those at moderate risk should also be considered for prophylaxis (Figure 2). Preferred agents include tenofovir or entecavir, typically continued for 6–12 months after completing immunosuppressive therapy, depending on the specific regimen. Careful assessment of chronic hepatitis B status, including HBV DNA and serology is essential before initiating immunosuppressive therapy. Relying solely on hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody results is inadequate in these patients.3

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

None

Corresponding Author

Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie, MD, MBA

Professor of Medicine, Clinical Educator

Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University

Division Director

Division of Hospital Medicine

The Miriam Hospital, 164 Summit Avenue, Providence, RI 02906