Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak began in Wuhan, China, and spread rapidly worldwide.1 As of 13th May 2022, 520 million cases have been reported across 213 countries and territories with more than 6.2 million deaths and more than 11,688 million have been fully vaccinated. In India, as of 13th May 2022, more than 43 million cases have been reported while more than half million people have died, and more than 19 million people have been fully vaccinated.1

Some individuals may visit hospitals on a routine basis for long-term diseases such as diabetes mellitus, allergies, heart disease, thyroid disease, hypertension, and others.2 Other individuals may visit hospitals for minor illnesses like flu-like symptoms, headache, burns, and lacerations. The fear of possible diagnostic and/or treatment delays in deadly or crippling conditions is likely one of the primary reasons why people would seek hospital care prior to the pandemic.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a severe reduction in hospital visits and even medical personnel discouraging some patients from seeking care at hospitals.2 The pandemic has affected access to healthcare indirectly, especially amongst patients with other ailments unrelated to COVID-19.2 The present study provides insights regarding the attitude and behaviour of the public towards visiting hospitals in the Indian states of western Maharashtra and southern Karnataka which were major hotspot areas for COVID-19 in India at the time of the investigation.

The purpose of the study is to determine how individuals react to ongoing pandemics, their willingness to visit hospitals, the reduction of hospital visits and the main reasons for not visiting hospitals. In addition to these significant concerns, other concerns are addressed to reduce the risk of other health-related deaths during the pandemic. Therefore, our study aims to ask and find out the answers to all these major concerns and address them adequately.3

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted between July-August 2021 in western Maharashtra and southern Karnataka states in India using Google Forms that were distributed through social media platforms. A total of 636 respondents responded to the survey and returned them electronically. The inclusion criteria were literate undergraduate or postgraduate individuals and those employed in the medical field at the time of data collection and those having access to an internet connection to fill out the online questionnaire. Individuals who did not fill out the form completely were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Ethical clearance was taken from the Institutional Ethics committee by presenting the informed consent sheet and patient information sheet.

Study Instrument and Administration

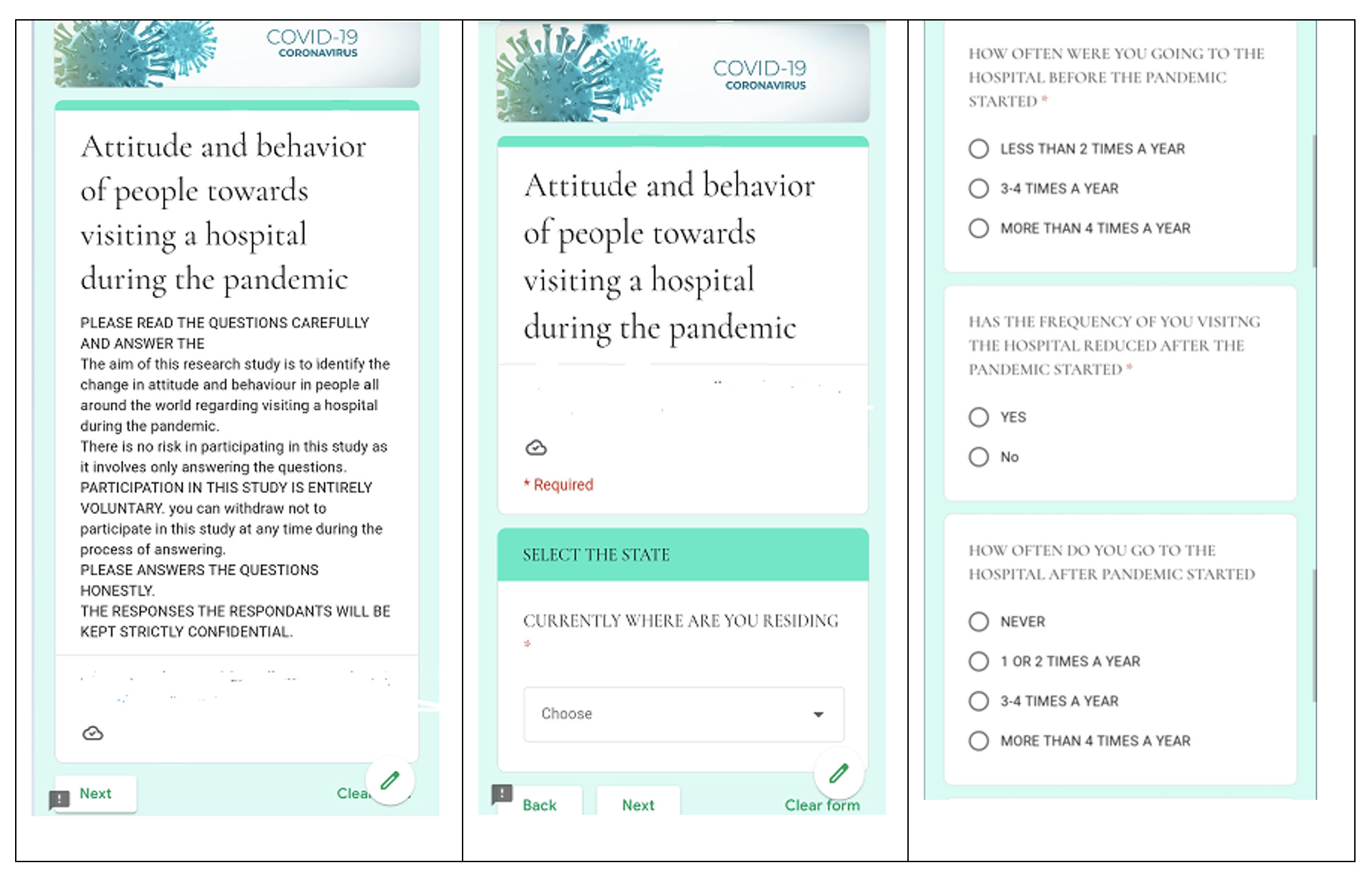

A short online questionnaire was developed after a review of a similar study.2 It comprised demographic characteristics of the respondents such as: age, sex, nationality, and profession.4 Outcome variables included the respondent’s attitude toward visiting the hospitals and the reasons for not visiting the hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ten questions were formulated for the online survey through Google Forms, as shown in Table 1. The electronic questionnaire was generated and entered into an online survey system. The link to respondents was distributed across social media platforms, and the data collection took place in June 2021. An example of a typical online Form is shown in Figure 1. Conventional non-probability sampling technique was used to analyse the questions given to the respondents.4

Data Analysis

There were 636 respondents representing individuals who were residing in two areas of India at the time of the survey form and who responded to the survey. This was confirmed by asking the respondents the state where they were currently residing. Google Forms data were downloaded, and data were analysed using different statistical tools. The tools were used to verify the normal distribution of variables and comparisons between groups for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was carried out to identify parameters more strongly associated with respondents’ attitudes and behavior of individuals towards visiting hospitals during the pandemic.

Results

The responses of 636 people were analysed, and the average age of the respondents was 39.9 years. 37.4% of the respondents had a postgraduate degree or higher and 35.8% were with an undergraduate degree. High school and college graduates made up the remaining respondents. Medical professionals made up 30.1% of the respondents. Figure 2 shows that there was a reduction in hospital visits for common illnesses after the pandemic began. While 62.6% of the respondents visited the hospital for common illnesses before the pandemic, only 39.1% visited the hospital during the pandemic for similar issues. However, 67% of the respondents went to the hospital for COVID-19 related illnesses whereas the remaining 33% opted to stay home or seek care through other means. Only 13.5% of the respondents had long term comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), etc.

Results showed that while 73% of the respondents visited the hospital 1-2 times a year for any illness before the pandemic began, only 49.7% of the respondents visited the hospital 1-2 times after the pandemic began. Approximately 59.7% of the respondents reduced their frequency of hospital visits during the pandemic due to fear of getting infected by COVID-19 in the hospital, 22.6% were afraid of getting infected by COVID-19 outside the hospital, and 15.7% were afraid of getting infected by hospital equipment; the remaining 2% had other reasons. Of the respondents that did not go to the hospital, 58.4% reported managing their health illnesses by consulting doctors online, 20.1% by self-medicating, 19.4% by calling a doctor at home for consultation or a lab technician to collect samples if necessary. Even after receiving both doses of vaccination, 53.7% of the respondents did not increase their frequency of hospital visits; however, 27.3% of the respondents had gained confidence in visiting the hospital after vaccination. Approximately 120 respondents (19%) were unvaccinated.

Discussion

Our study observed that around 62.6% of the respondents’ visited hospitals for common illnesses before the pandemic started, whereas about 60.9% reported not visiting the hospital for common illnesses after the pandemic started. The study also showed that 73% of the respondents visited the hospital 1-2 times a year for any illness before the pandemic started but after the pandemic started only 49.7% of respondents visited 1-2 times a year. 74.8% of the respondents reduced going to the hospital after the pandemic started.

The major reasons for the reduction in willingness to visit hospitals was due to the fear of becoming infected within the hospitals (59.7%), outside the hospitals (22.6%), and due to hospital equipment (15.7%). 58.4% of the respondents attempted to manage their health themselves by online consultation of doctors, 20.1% by taking medications on their own, 19.4% by calling the doctor or lab technician home for sample collection and others by home remedies. Individuals found different ways to avoid going to the hospital and instead obtained treatment at home. At-home treatment may work but as the provider cannot see the patient in-person, many unanticipated diagnoses may be left out and the patient’s condition may worsen.

Most (86.5%) of the respondents were not under any long-term treatments for conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure. This is likely due to the mean age group of the respondents being relatively young (39.9) years. Long-term diseases increase the severity and mortality of COVID-19. Thus, it is imperative that care for patients with long-term diseases must be continued to reduce further complications and the risk of death.5,6 53.7% of the respondents did not increase the frequency of visiting hospitals even after getting fully vaccinated and only 23.3 % of the individuals gained the confidence to visit the hospitals after vaccination. This suggests that the vaccination drive in India was still not yet sufficient to return individuals to their previous patterns of seeking medical care. Patients should continue to be evaluated for their potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital facility even after getting fully vaccinated.7

Some hospitals attempted to reduce the number of patients seeking care at their location to decrease the risk of coronavirus transmission to other patients or health care workers within their practice.8 Surgical and procedural specialties and paediatrics remained the most affected by the relative decline in visitors. Other specialties like mental health and primary care for adults have seen less decline. In school-aged children, the rebound was more minor, while in older adults, it was more prominent.3 Social distancing and the “lock-down” of the country contributed to a steep decline in the emergency room visits in most hospitals during the pandemic.2 Reducing hospital visits may lead to delayed management of complications of chronic illnesses, posing significant problems with cancer, diabetes, and others in the long run.2 A study in the pandemic period on cardiac patients suggested that there was a significant decrease in heart failure admissions compared to the rolling daily average, but an increase in heart failure deaths in the community. This analysis can also be applied for other chronic illness patients.9 Hospital visits among completely vaccinated people have declined significantly and take place rather less often than unvaccinated individuals as vaccination has enhanced regionally. If hospitalization is necessary, elderly with significant comorbidities, regardless of vaccination status, are at a high risk of severe outcomes.10

Instead of physical visits to hospitals, provision is made to consult through telephone or other virtual platforms. The number of online consultations has increased for upper respiratory tract infection, psychological conditions, and COVID-19-related investigations, and interventions. The increased online consultations have increased demand for the relevant clinical services and reduced hospital visits, thus potentially decreasing the COVID-19 spread. Online consultation is not so useful for patients in India as it is limited to only those who have access to the internet or good network access for mobile calls. This makes it more challenging for providers to diagnose such patients and ultimately leads to unavoidable hospital visits, thereby also increasing the risk of transmitting COVID-19 infection to these patients.11–14

Our study has several limitations. One limitation of our study is the small sample size and representation of only literate people. The survey questionnaire was available in English and distributed in an online format, further introducing selection bias favouring English-literate people and those with access to the internet. Lastly, the mean age of our respondents was 39.9 years, hence older age groups with multiple chronic illnesses such as DM and HTN were not well represented.

In conclusion, this study reveals that there was a drastic reduction in willingness to seek hospital -based care in India due to the change in attitude and behaviour of the public towards visiting the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Much of the reduction may be attributed to the fear of becoming infected with COVID-19. Hospitals should seek to create strategies to manage health care access amongst patients, such as designating separate hospital blocks to address illnesses other than COVID-19, along with other similar measures. By doing so, the public may be more likely to trust the safety of hospitals. This may motivate them to seek hospital care early in order to prevent a late diagnosis of life-threatening illness or crippling complications.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the respondents in this study for volunteering their time and opinion on this important subject matter.

Financial support and sponsorship

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author

Manaswi Shamsundar

Aditya Garden city 3D/4

Warje, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Email: manusham0604@gmail.com

ORCID number: 0000-0002-5705-0864