Introduction

Academic hospitalists face challenges in consistently generating traditional scholarly output, such as publications.1 There are many potential barriers to academic productivity by hospitalists, including high clinical volumes, limited non-clinical time for academic endeavors, faculty inexperience, and limited mentorship.2,3 Recommended strategies to increase traditional scholarly output in hospital medicine are limited, in part because many hospitalists are not motivated by traditional markers of academic success.1,4

Non-clinical domains of academic interest for hospitalists include medical education, quality improvement (QI), leadership and administration, informatics, and research. Protected time and mentorship are variables that portend success in this work, and the lack of these discourage academic hospitalists from pursuing academic projects.5,6

Throughout the country, research and publications are not necessarily a major driver of academic promotion for hospitalists, with one 2012 study finding that full professors at established academic hospitalist programs had a mean of only seven first-author papers.6 Nevertheless, a 2011 survey of hospitalists who had already achieved the higher ranks of associate or full professor found that faculty maintained a traditional view of what was most important in achieving promotion: peer-reviewed publications.7 These two studies were done over a decade ago, and, as the field of hospital medicine and promotion pathways at medical schools continue to evolve, our single-site experience could inform the conversation around redefining promotable activity to align with what hospitalists value.

There is limited literature on identifying what does encourage clinicians in this field to engage in non-clinical work, with one study noting that recognition by patients and colleagues was important to hospitalists in driving career satisfaction.8 The aim of our needs assessment study was in part to enhance understanding of unique factors that motivate hospitalists and influence their measurement of personal career success, so as to inform approaches that promote greater academic engagement and productivity in the hospital medicine field.

Methods

We conducted a confidential online cross-sectional survey of academic hospitalist faculty members at two hospitals in North Carolina: a 957-bed tertiary referral center and a 369-bed university-affiliated community hospital. The study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board.

The survey instrument was 27 questions. It was disseminated to all 77 hospitalist attending physicians at the two hospitals who also had faculty appointments in the affiliated School of Medicine. The survey was conducted via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and participants were provided with their own unique, anonymous link to prevent multiple participation. Respondents were not required to answer every question, obviating a need to include a “none of the above” option if academic engagement or productivity did not apply to them.

We developed the questions based on prior literature about career success, satisfaction, and burnout in hospital medicine.9 Questions focused on (1) drivers of selection of a career in academic hospital medicine, (2) academic engagement, defined as participation in projects outside of direct patient care, (3) self-identified measures of professional success, (4) experience with mentorship and faculty development, (5) academic productivity, defined as completion of posters, oral presentations, or peer-reviewed publications, and (6) burnout. In assessing non-clinical protected time, we differentiated between grant-funded research and internally funded time, ie, time funded by the medical school or health system for an individual to dedicate to a particular project or leadership role.

We assessed burnout with a single item adapted from the tedium index.9,10 We used descriptive statistics to summarize responses and a multivariate logistic model to evaluate the association between burnout and academic productivity, existence of an identified mentor, protected non-clinical time, and years in practice.

Results

Survey response rate was 79% (n=61). Respondent demographics are described in Table 1. Factors for seeking a career in hospital medicine varied amongst respondents (Figure 1A).

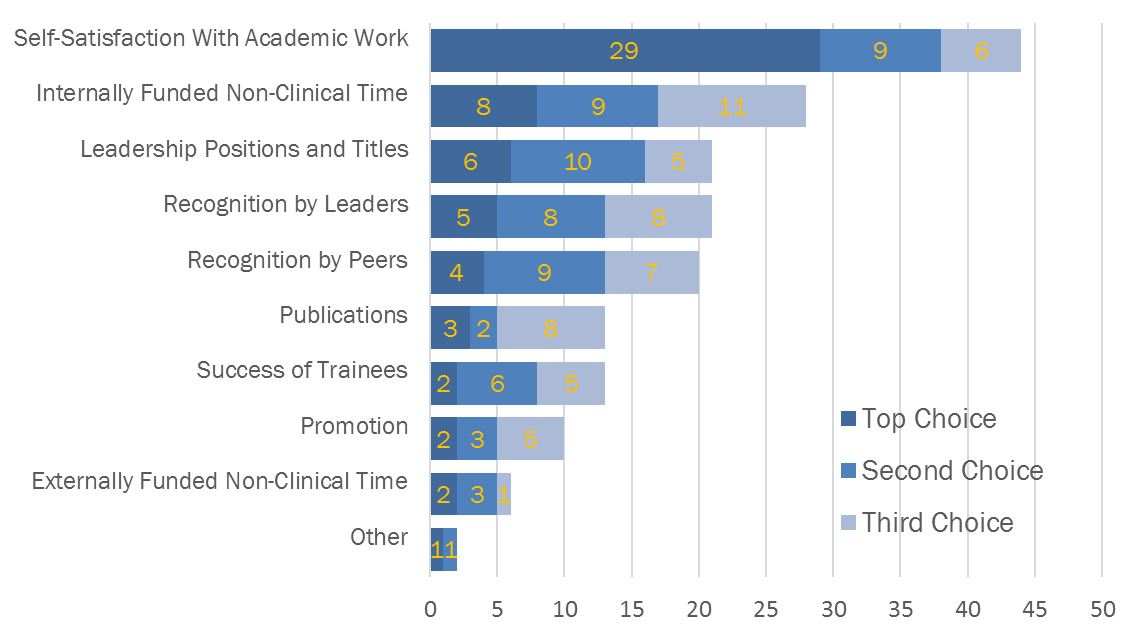

Most respondents (82%) reported already being academically engaged, and most also expressed interest in more opportunities within an area of non-clinical, academic interest (69%). Self-satisfaction with academic work (25%) and earning internally funded non-clinical time (16%) were the most frequently cited measures of career success in hospital medicine (Figure 1B), surpassing traditional success measures in academic medicine, such as publications (7%), rank promotion (6%), and external grant funding (4%).

Using the single question assessment, 39% reported burnout. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that mentorship, academic productivity, protected non-clinical time, and years in practice were not significantly associated with burnout.

Discussion

Academic hospitalists in our study were not primarily motivated to pursue academic projects in order to achieve traditional measures of scholarship and promotion, such as publications and grants. Despite this, they reported a desire to increase their level of academic engagement beyond an already high baseline level. These findings are consistent with previously published qualitative work that highlighted how measurement of academic success has evolved among academic hospitalists.3,4

Promotion and progress through the academic ranks from instructor to full professor at the institution in our study confers an honorific title that is not accompanied by additional remuneration or any linked modification to clinical complement. Intrinsic motivation and interest in the non-clinical work is a likely driver of academic engagement for hospitalist faculty. It is not surprising that publishing, perceived as required for rank promotion, is not prioritized by the respondents in this study.

There was not exact correlation between which domains hospitalists indicated as areas of academic interest and the domains they indicated as their area of academic productivity. For example, 21.2% of respondents at the tertiary site reported academic productivity in the field of quality improvement, though only 2.9% cited it as a primary area of interest. This could reflect the inherent team-based work of QI engaging more faculty or it could suggest that there may be less of a barrier to engagement and productivity in this domain than another, more preferred field.

Strengths of this study included a high survey response rate and inclusion of hospitalists from tertiary care university and community/academic hybrid sites, enhancing the applicability to other academic hospital medicine groups who practice across diverse clinical settings. While we had a high response rate, the sample size (N=77) limited our ability to detect associations in multivariate analysis. We believe the high response rate of 79% mitigated the potential for respondent bias in establishing our baseline level of academic engagement. Our two sites were within the same health system, and both have an academic affiliation. This may limit applicability, though this survey could be replicated at more institutions to generate more generalizable conclusions. In addition, identifying and focusing on differences between community sites and tertiary sites can inform tailoring faculty development and mentorship programs to each hospital rather than a blanket institutional response across an entire hospital medicine academic group.

The level of burnout reported in our survey was high, and it was not significantly associated with any singular covariate we investigated. Future studies could investigate drivers of this sentiment or changes over time. This study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had an outsized impact on burnout and academic productivity. Further areas of research include repeating this survey in the post-pandemic academic landscape.

Conclusion

Our needs assessment found that hospitalists currently engaged in academic work are not primarily motivated by the achievement of traditional measures of academic success: publication and rank promotion. As the field of academic hospital medicine grows, an important area for further study is understanding what approaches can align with hospitalists’ motivators to promote academic productivity. Whether efforts to promote engagement and productivity in a hospitalist-centric manner can be protective against burnout should be explored further.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The authors each declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding

The Duke BERD Methods Core’s support of this project was made possible (in part) by Grant Number UL1TR002553 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCATS or NIH.

Corresponding Author information

Suchita Shah Sata, MD (Twitter @SuchitaSata)

Assistant Professor of Medicine, Duke University Hospital Medicine Programs

40 Duke Medicine Circle, DUMC 3534, Durham, NC 27710

T: 919-681-8263; F: 919-668-5394

ORCID: 0000-0002-9773-6174

Email: Suchita.Shah.Sata@duke.edu