Background

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common disease condition of varying degree of severity. Conditions and external factors which propagate vascular damage, circulatory stasis, and hypercoagulability, known as Virchow’s triad, lead to the formation of intravascular thrombi. Clinical features of swelling, edema, pain, and/or warmth are found in proportion to the luminal narrowing related to the thrombus. Disease progression exists along a spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic to complete venous occlusion. Of note, the lower extremity venous system is most often affected, with the left common iliac vein being the most implicated in external compression.1

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old woman with a past medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to hospital with sudden onset swelling and redness of her left leg. One day prior, the patient was in her usual state of health performing household chores and grocery shopping when she noticed some discomfort in her left posterior thigh which she described as a constant, non-radiating ache rated 3/10 in severity. It did not initially interfere with her daily activities but within 24 hours the patient noted moderate swelling and redness in her left leg which was most noticeable in her left upper thigh along with a blueish discoloration on her left foot. She now suspected that her symptoms were related to vascular insufficiency and began walking a great deal to re-establish blood flow. Despite her efforts, swelling and discoloration worsened and had now spread to involve the entirety of her left lower extremity. She reported a 50-pack-year smoking history.

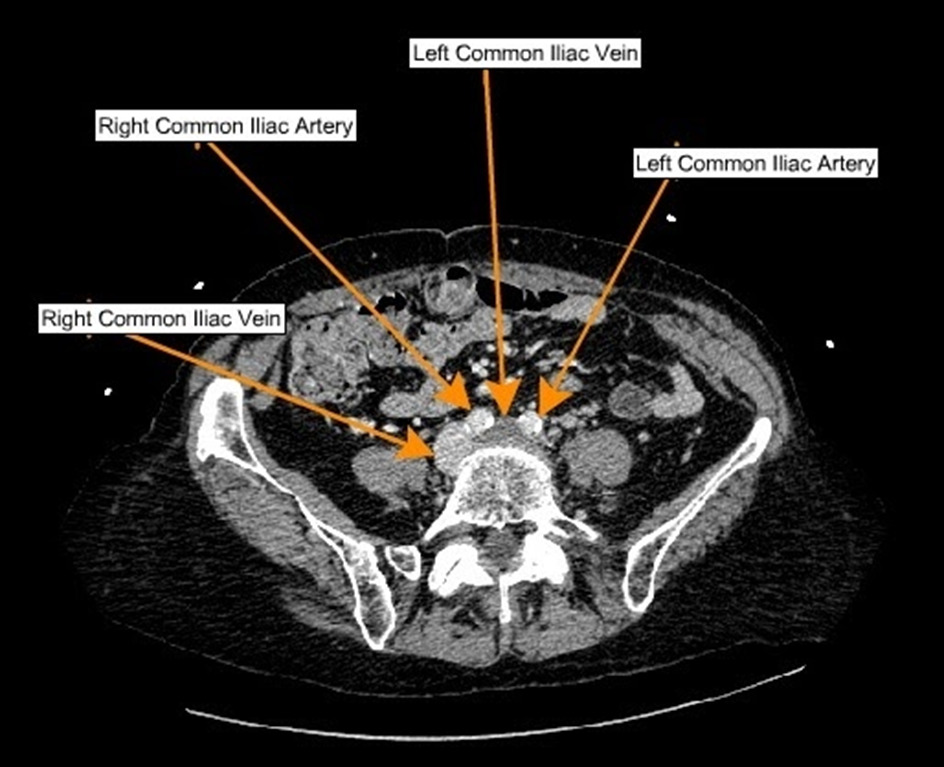

Physical examination included heart rate of 119 beats/min, blood pressure of 136/78 mmHg, and oxygen saturation of 95% on ambient air. The left lower extremity was markedly erythematous and swollen without calf tenderness (Figure 1). The sole of her left foot appeared mildly cyanotic. Bilateral varicose veins were present, and peripheral pulses were normal. A complete blood count and a comprehensive serum metabolic panel were within normal limits. Venous duplex of the left lower extremity showed acute deep venous thrombosis (DVT) involving left femoral, popliteal, great saphenous, posterior tibial, and peroneal veins. There was no evidence of DVT in the contralateral extremity. Due to the involvement of major lower extremity veins and the presence of swelling, cyanosis, and violaceous discoloration of the entire extremity; phlegmasia cerulea dolens was diagnosed. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with pulmonary angiography showed bilateral lower lobe pulmonary emboli and a spiculated mass in the right upper lobe measuring 3.4 x 2.3 x 2.1 cm. The presence of extensive unilateral DVT led to further investigation of the extent of the clot proximally. A CT venogram of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusive thrombi in the left common, internal, and external iliac veins, extending into the left femoral vein with compression of the left common iliac vein origin by the right common iliac artery consistent with May-Thurner syndrome (MTS). See Figure 2.

The patient was treated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) infusion in anticipation of catheter-directed thrombolysis. The patient declined to undergo thrombolysis and further evaluation of her lung mass. Her symptoms improved with UFH therapy and was she was discharged on oral rivaroxaban daily.

Discussion

May-Thurner syndrome is a venous compression syndrome, also known as ilio-caval compression syndrome, induced by compression of the left common iliac vein by the overlying arterial system against the underlying lumbar vertebrae. MTS is more common in female patients between the ages of 30-50 years who present with symptoms of left lower extremity, swelling, skin hyperpigmentation, ulceration, varicose veins and left lower extremity DVT.1–4 Currently, there are no standardized criteria to establish this diagnosis.5 A venous duplex ultrasound remains the most reliable test for evaluating venous thrombosis in lower extremity swelling.6 Additional imaging includes magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and intravenous ultrasound (IVUS), which are useful in revealing the precise location of the compression and allow for the assessment of vascular stent sizing and placement.7,8 Treatment includes endovascular modalities, such as catheter-directed thrombolysis and venous angioplasty, which have been noted to be successful and less risky than surgery.5

MTS is thought to be present in over 20% of the population; however, it is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis of DVT, particularly in patients with other risk factors that can increase the likelihood of hypercoagulability.9 Clinically, nearly 3% of all lower extremity DVTs may be attributed to MTS-related DVT though it is likely underdiagnosed.10

Rare manifestations of MTS include phlebitis and phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD).5 PCD is defined as an acutely exacerbated DVT that occludes the entire major deep venous system including the collateral vessels.11,12 Prolongation of the disease course results in venous hypertension, impairing both capillary diffusion and arterial circulation culminating in venous gangrene and massive tissue necrosis.12 Early diagnosis is critical for the reduction of overall morbidity and mortality. The main feature of this condition is cyanosis, which begins peripherally. As cyanosis and venous congestion worsen, patients may develop cutaneous bullae and necrosis.13 This vascular condition is highly emboligenic and may be complicated by pulmonary embolism. Diagnosis of Phlegmasia requires a detailed history and physical exam. Emergent signs include blistering or skin necrosis, arterial or neural compromise, and venous gangrene which requires immediate efforts to preserve tissue viability.14 Definitive management includes anticoagulation, catheter-directed thrombolysis, thrombectomy, or any combination of the three depending on the severity of the presentation.14 The majority of patients will respond to treatment with fluid resuscitation, aggressive elevation, and anticoagulation.14 Additionally, a fasciotomy can be performed if compromise of the arterial and/or venous blood supply to the limb exists.14 Although not often encountered in patients who present with phlegmasia and venous gangrene, compartment syndrome should be considered.14

Prompt diagnosis is critical in patients with MTS and PCD to avoid complications. A healthcare management team consisting of a vascular surgeon, a hematologist, and potentially a critical care specialist is necessary.14 Given the risk of limb loss and potentially death, early diagnosis is vital. Once confirmed, the patient requires fluid resuscitation, elevation of the affected extremity, and anticoagulation.15

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this manuscript.

Author Contributions:

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

• Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

• Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

• Final approval of the version to be published; AND

• Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

None.

Corresponding Author

Monarch Shah,

Department of Internal Medicine,

Saint Peter’s University Hospital.

monarch.shah08@gmail.com

Current Address:

1303, Knoll Street,

Charlottesville,

VA 22902, USA.

908-392-8598