Background

Epiglottitis, or supraglottitis, is inflammation of the glottis and its surrounding structures.1 Despite being relatively rare, even mild cases can be highly distressing for patients and potentially fatal due to the epiglottis’ proximity to the airway. Traditionally, epiglottitis has been thought to be a disease of pediatric populations, although in recent decades the epidemiology has shifted in middle- and high-income countries, to include more adults than children due to the advent of large-scale vaccination and prevention measures in children.2 Notably, disease presentation differs in some ways between pediatric and adult populations, with respiratory distress, agitation, and ‘tripoding’ more commonly seen in children and dysphagia, pharyngeal soreness, and less severe disease more commonly seen in adults.2,3

The most common cause of epiglottitis in both adults and children remains bacterial epiglottitis due to Haemophilus influenzae (H. Flu), although other contributing bacteria include most commonly Group B Streptococcus and other Streptococcus species.3 Viral causes have been identified, both less commonly and less severe, and it is worth noting that any inflammation of that region can induce epiglottitis, including inhalational injury and caustic ingestion.4

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old woman, heavy smoker with history of diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease developed sore throat, progressive onset dysphagia, and hoarseness for one month. Her symptoms worsened one week prior to presentation, with orthopnea and near complete loss of her ability to phonate. She denied any subjective fevers, chills, nausea, weight loss, or night sweats throughout this time course. She had no personal or family history of laryngeal masses, glottis masses, and denied family or personal history of malignancies of the head, neck, or gastrointestinal tract. She had a ten pack year smoking history with twenty years of active smoking, and was consistently smoking one pack per day for a few years before this episode. She denied any sick contacts or trauma/insults to the airway in the months leading up to her symptom onset.

Physical examination was notable for acute respiratory distress, stridor, and hoarse voice without tripoding, drooling, or any respiratory findings on pulmonary exam. She had no palpable neck masses or lymphadenopathy, and no tonsillar erythema or hypertrophy. She was endotracheally intubated on arrival for airway compromise, and a nearly obstructing, well circumscribed glottic mass was noted on intubation.

Lateral neck radiographs were not performed given acuity of presentation and visualization of mass on intubation. Computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated diffuse soft tissue thickening of the glottic and supraglottic larynx including left greater than right aryepiglottic folds, with near complete effacement of the airway, and a 1.4 cm polypoid mass extending inferiorly into the subglottic trachea (Figure 1). Initial lab results revealed a leukocytosis of 14,000/mL without bands with no other derangements on metabolic or hematologic labs. Of note, by the next morning, without any antimicrobial therapy, white cell count was back in normal range at 10,900/mL.

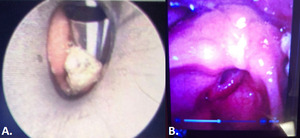

On the second day of admission, she underwent tracheostomy and direct laryngoscopy that revealed an obstructive well-circumscribed glottic mass with supraglottic edema and a laryngeal mass (Figure 2). Glottic mass biopsy demonstrated acute inflammation, granulation tissue without tumor cells. Sedation was progressively weaned until the 6th day of admission when she became tachypneic, oliguric, and became febrile to 101.2 degrees F, prompting empiric coverage with antibiotics. Infectious workup with plain chest radiograph, urinalysis, and blood counts was non-revealing. Blood and sputum cultures taken during this time grew Group G Streptococcus, and the patient was started on intravenous ceftriaxone. She improved clinically over the next ten days. Bedside laryngoscopy done during tracheostomy tube exchange showed complete resolution of the previously identified glottic mass (Figure 2). The patient was subsequently decannulated and discharged home. Follow up two weeks after discharge demonstrated complete resolution of the previously described lesions with no residual scarring.

Discussion

The presentation of epiglottitis typically consists of symptoms resulting from airway compromise due to reduction in the cross-sectional diameter of the airway. This can involve respiratory distress evidenced by tachypnea, tachycardia, and use of accessory muscle use during respiration. Certain characteristic clinical features of supraglottic compromise should raise high clinical suspicion for epiglottitis, such as ‘tripoding’ which describes positioning oneself with both arms outstretched supporting a trunk that is leaning forward with extension of the neck and chin to maximize airway diameter. This can also come with drooling, stridor, hoarseness, and ‘hot potato voice’ which is muffled speech resembling that one might expect from someone with hot potatoes in their mouth. Patients may or may not complain of typical infectious symptoms such as fevers, nausea, vomiting, night sweats, chills, and general malaise. In terms of timing of symptom onset, presentation can be acute or subacute. Acute epiglottitis is described as rapid in onset over hours to days, more typically causing febrile symptoms, and most commonly triggered by Hemophilus influenzae. Subacute epiglottitis caused by non- Hemophilus influenzae organisms tends to be more indolent in onset over several days to weeks and is oftentimes less severe.5–8 Diagnosis can be made clinically and can be assisted by lab markers demonstrating signs of infection such as leukocytosis or radiographic imaging such as lateral chest x-ray, which can show enlargement of the glottic structures commonly referred to as ‘thumb sign’.2,8 CT imaging can also demonstrate enlargement of the involved structures, as can direct visualization through laryngoscopy which typically demonstrates uniformly enlarged glottic structures with surrounding edema and ‘cherry-red’ inflammation.2,8

The most common cause of epiglottitis in both adults and children remains bacterial epiglottitis due to Haemophilus influenzae, a gram negative coccobacilli, despite widespread vaccination and overall reduction in incidence. Other contributing bacteria include most commonly Group B strep and other strep species.3 Viral pathogens that target the upper respiratory tract can also cause epiglottitis, both less commonly and less severely. It is also worth noting that any inflammation of the glottic area can induce epiglottitis, including inhalational injury or caustic ingestion.4

Onset of epiglottitis caused by the strep species (subacute) tends to be more insidious in onset than epiglottitis from Hemophilus influenzae. Broadly speaking, epiglottitis secondary to strep species is relatively common, although case reports of epiglottitis caused specifically by group G streptococcus are rare but present in the literature.2,9 Like other documented cases of Group G strep epiglottitis, this patient’s onset was subacute in nature. Additionally, this patient’s progression to bacteremia is unique, and is likely a byproduct of initial workup more suggestive of malignancy which resulted in her infection going untreated for several days after intubation.

Management of epiglottitis involves supportive therapies of the airway, including intubation when features of airway compromise are present, such as ‘tripoding’, stridor, and use of accessory muscles of respiration. Administration of glucocorticoids to reduce airway edema are thought to have positive effects on reducing airway compromise, although this has notably never been demonstrated due to lack of any prospective randomized controlled trial on the subject. Clinicians tend to reserve steroid treatments for patients with more severe compromise, and therefore retrospective trials associate steroid use with longer hospitalizations, which makes drawing conclusions on steroid efficacy confounded and unreliable.2 Treatment of the suspected organism through antimicrobials is recommended in the cases of suspected bacterial epiglottitis and may depend on the antibiogram profile of particular regions and institutions. Generally speaking however, given Hemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus species’ role as the most common organisms, antibiotic coverage with combination of gram-positive and gram-negative coverage given intravenously such as a penicillin with a beta lactamase inhibitor, third-generation cephalosporins, or quinolones is likely adequate as empiric treatment.

Epiglottitis, by virtue of being a cellulitis of the glottis and surrounding structures, can also involve nearby components of the airway. However, the authors of this article were unable to find any case reports of epiglottitis presenting with laryngeal polyps, making this case unique. One may argue that given the diagnosis, this may actually have been a mucocele erroneously characterized as laryngeal polyps on imaging. Regardless, the underlying conclusion remains that an epiglottitis mass can resemble polyps and may lead to the wrong diagnosis of malignancy, especially given negative biopsy results as was the case for this patient. This case also highlights an unusual manifestation of group G streptococcal disease. Group G Streptococcus is an uncommon pathogen, accounting for 1.5 percent of bacteremia in adults.10 However, recent trends across several nations have noted increasing proportion of infection cause by Group G strep over the last twenty years.10 Syndromes precipitated by Group G Streptococcus are most commonly pharyngitis, septic arthritis, skin and soft tissue infections, and bacteremia, but also includes endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis among others.2,11 In conclusion, epiglottitis, while rare, can manifest with indolent onset course, include surrounding airway structures, and should remain in the differential for glottic airway obstruction even in the presence of a mass resembling laryngeal polyps, especially if biopsy shows lack of malignant tissue.

Corresponding Author

Juan Lopez Tiboni, MD

Internal Medicine Resident

Pennsylvania Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine

800 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA, 19106, USA

Phone: 215-316-5151

Email: LopezTiJ@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

None.

_images_of_laryngeal_and_glottic_mass_on_admission.png)

_images_of_laryngeal_and_glottic_mass_on_admission.png)