The foundation of every story is a narrative arc with a beginning, middle, and end. Illness also follows a similar pattern; however, its implications are more difficult to process. While stories have always been a part of my life, I never expected that I would be the protagonist of an illness story. When my story began, I did not understand the scope or severity of the events. It seemed like things were going okay until suddenly they weren’t. It was my mom who realized that this illness was greater than she, I, or any of my family members could have ever imagined. Late one night, she drove me to the hospital, with the hopes that this illness story would eventually be resolved.

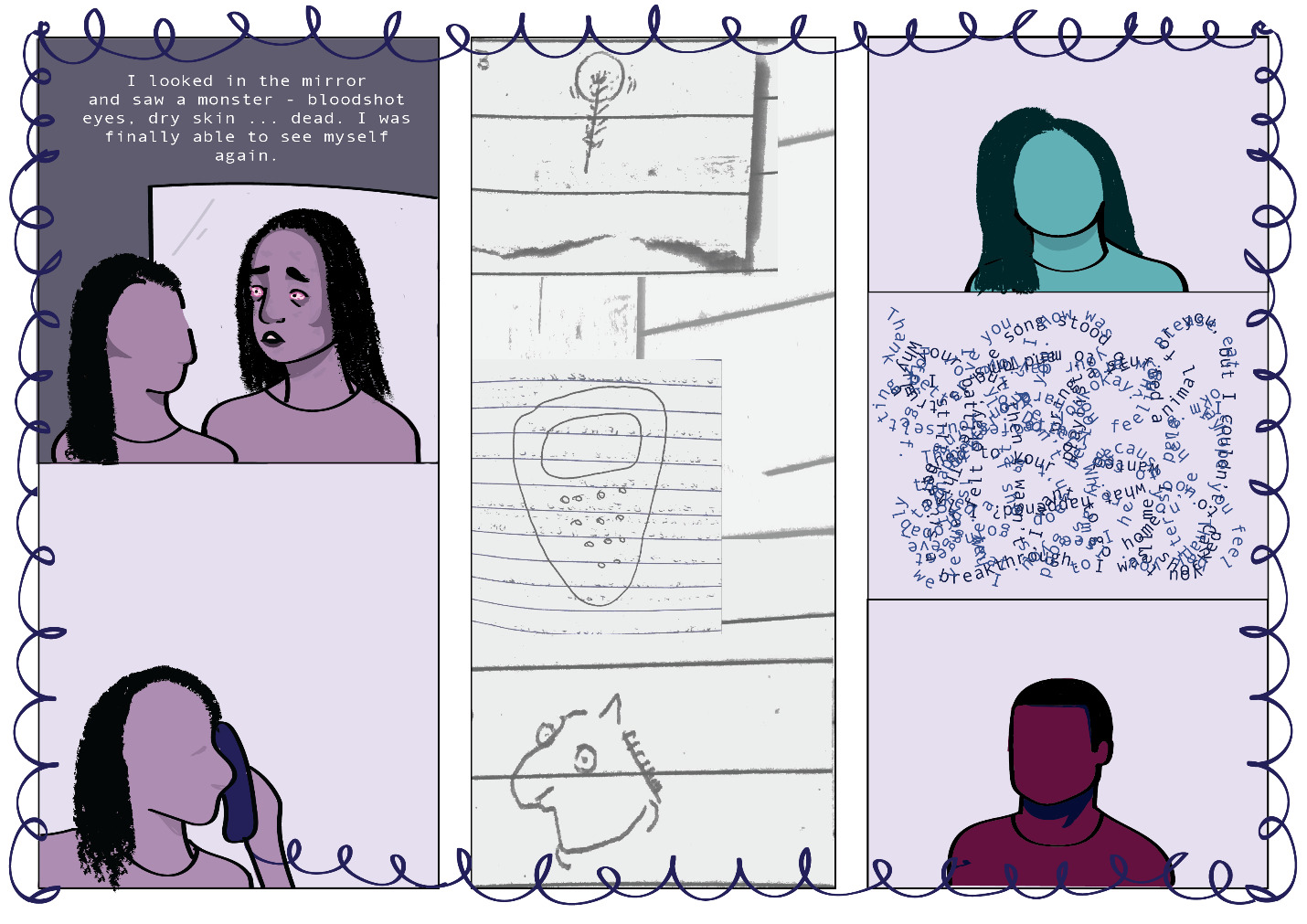

At first, I was skeptical of the hospital setting. I mostly kept to myself, not engaging in the clinical process. I grew impatient with my recovery. I often asked when I would be able to go home, and I wanted a quick ending to this story. My frustration turned into sadness when I realized I would be in the hospital for an indefinite amount of time until I was well. That ambiguity hit me hard; I found no meaning or comfort in it. While the world was moving on, it felt like I was stuck. I barely talked during my time in the hospital, and when I did, it was with my family members on the phone. While I don’t remember what the conversations entailed, I do remember how they sounded. There were long silences at times, filled with thoughts I would never hear. Pauses that prolonged the experience of my illness story. Their words were slower, perhaps so I could understand better, and their tone carried a heavy weight. I often wondered why my family members sounded the way they did. As I navigated my own illness story, my family remained a gauge of how I was doing. Their voices reflected my progress.

In my hospital journey, a journal and a mirror were important items for me. Although my journal mostly contained fragmented ideas or unpolished drawings, it was something I could trust within the medical landscape, and it never left my side. The mirror helped me mark a turning point in my progress. I had looked at my reflection during my hospitalization a few times before, but after one week in the hospital, I truly saw myself, and I was horrified. I felt naïve for believing that my story of illness was over. Why am I still here? Because you’re ill - and it shows. I was relieved that I wasn’t at home and that my family members could not see me like this. If I was scared, how would they react? Overwhelmed with shock, I took the time to write down this experience in my journal. After reconciling how my outward appearance reflected my internal condition, I saw the hospital in a new light. It wasn’t designed as a place to trap me; it was designed as a place for me to heal. With that, I became more responsive to treatment and more receptive to the hospital setting. Trust and curiosity replaced the skepticism and fear I originally had. I asked questions of the clinicians I met, writing their words and perspectives in my journal. They weren’t an obstacle to my illness story, but rather key characters within the narrative. I accepted where I was in my story, not rushing the process, but making sure to find meaning in every part. When I talked to my family on the phone, there was a noticeable lightness in our voices and even laughter in our conversation. There was joy, relief, and hope in their voices and our words. My mom described this as a “breakthrough,” and it was. A few days later, I was discharged from the hospital, feeling better than okay. Before I left, I made sure to ask for more blank journals to take with me so that I could continue documenting my story.

Narrative medicine has continued to enrich my life. Since my own illness story, I have helped other patients tell their stories. These experiences have shaped my appreciation of the patient experience which I highlighted in this visual narrative. The hospital experience involves multiple characters, perspectives, and storylines to ultimately engage with the protagonist, our patient. The importance of both the first-person perspective of the patient but also the external perspectives prompted me to depict both the patient and family in this triptych. Having the clinician and family input is crucial to recovery. In this piece (Figure), I illustrate the patient’s story and the family’s story, connected by the phone. The center panel depicts significant entries in the journal, acting as the bridge to recovery. Creating this piece had a sobering effect on me. I used colors that remind me of the feelings my family members and I had — fear, sadness, and anger. As I drew, I often had to pause and think about the unspoken feelings of my own family. While I have come to accept my own experiences with illness, it is still difficult for me to think about what my family went through. I was protected in the bubble of the hospital setting, but my family members were not. They had to handle life’s responsibilities while also processing my illness. My sister and I message each other daily, and she continued to send messages to my phone when I was hospitalized. I only saw these after I came home. My mom was in daily conversation with the clinicians. As she was still working during my hospitalization, she would often drop off items for me late at night. My brother listened to music from an old playlist of mine and urged my mother to take care of herself, reassuring her that I would eventually get better. Just as phone calls could not fully express the entirety of my illness story, words may not fully encompass the experience of illness. For that reason, I chose to keep the text in this cartoon minimal or obscured.

It is a privilege that I can share this story about the emotional landscape of the hospital setting. The beauty of my own experience with illness was not only that I recovered but I also grew from it. I hope that I can tell more stories in the future, especially those of illness, that resonate with others.

Corresponding Author

Obarianasemi Owate-Chujor

Brown University, Providence, RI, USA

Email: achujor00@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

None.