The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated effects on the healthcare system have led to a renewed emphasis on provider wellness, the need for resilience, and the concept of emotional and adaptability quotients (EQ and AQ).1,2

Financial pressures on healthcare institutions have also led to increasing demands for hospitalists to redouble efforts in optimizing operational effectiveness and meeting institutional metrics. Hospital medicine is therefore dealing with many of its persistent challenges and new ones arising from the new currents in our healthcare environment.

Building Teams in Hospital Medicine

The need for agility in hospital medicine operations occurs when new winds blow in the workforce domain. The major ones presently are:

-

Great Resignation: This refers to the increased rate at which U.S. workers resigned from their jobs starting in the spring of 2021, amid strong labor demand and low unemployment even as vaccinations eased the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anthony Klotz, a professor of business administration at Texas A&M University, coined the term in May 2021.3

-

Quiet quitting: A phenomenon outlined in a September 2022 Harvard Business Review article by Professors Anthony C. Klotz and Mark C. Bolino, “Quiet quitters continue to fulfill their primary responsibilities, but they’re less willing to engage in activities known as citizenship behaviors: no more staying late, showing up early, or attending non-mandatory meetings.”4

Hospitalists have not faced the massive wave of the “Great Resignation,” which has taken place in outpatient primary care and other segments of our healthcare system. We have, however, not been spared the concepts of re-alignment and quiet quitting.

Re-alignment of goals to balance family and psychosocial needs has resulted in providers cutting back on their professional (clinical, academic, and/or administrative) time to anywhere between 0.5-0.9 full-time equivalent status (FTE). Quiet quitting is characterized by personnel doing the barest minimum of their required job obligations and little or no engagement in other group activities. Some of these additional group activities, which may include group academic and operational endeavors, and meetings, significantly affect the diffusion of best practices. Persistent lack of engagement may result in a degradation of the practice’s “culture of excellence” and chronic negative effects on the group morale while eroding gains in the group’s operational metrics.

Resignation and re-alignment are readily identified and can be addressed when filling vacancies with new providers. The practice need is not for any “warm body” but for professionals possessing the skills and attitudes required to enhance team goals and objectives.

Addressing provider recruitment requires answering 3 main questions.

-

What is the vision of the group/team?

-

Do all team members know and share the group’s/ team’s vision?

-

Do all individual team members possess Strategic Fit in order to enhance group/team performance?

Strategic Fit

Providers cannot be expected to wholly embrace a vision and set goals that are not clearly articulated. Leadership is responsible for making these clear and succinct. The hiring process and ongoing provider evaluations should place emphasis on ensuring explicit knowledge and adoption of the vision. Providers who cannot adhere to the vision should not be hired to join the group. This is a difficult decision when dealing with staffing constraints. In the long run, it is better to use temporary measures to address staffing issues rather than bringing on an individual or individuals unlikely to share the group’s vision and goals.

Providers who repeatedly do not meet set performance goals should receive constructive feedback focused on improvement but may ultimately move to other systems which may provide a better fit. Group leadership must balance group needs and provider capabilities to avoid negatively impacting group performance and individual hospitalist careers by continuously monitoring indicators of performance and fit.

The significance of Fit has yet to be emphasized in much detail in hospital medicine. This is important because individual activities affect the group/team. One cannot commit to a goal and try to attain it without being committed to the individual processes involved.

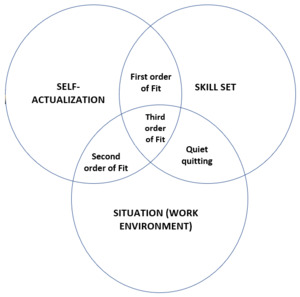

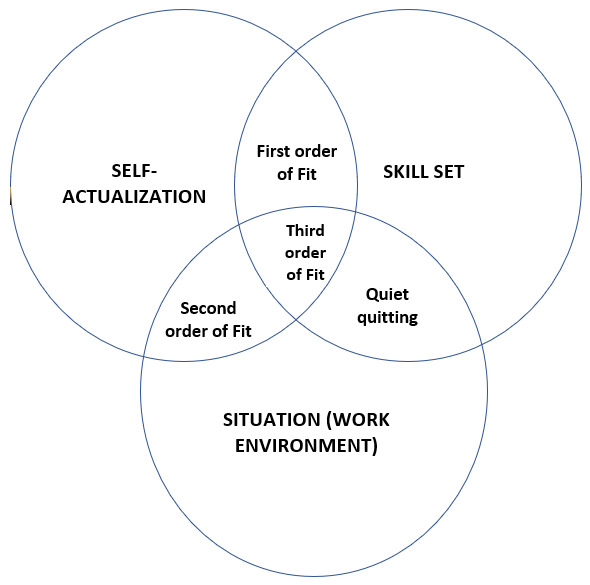

There are 3 orders of Fit (Figure 1):

-

First order of Fit is simple consistency: Providers’ activities are consistent with team/group norms.

-

Second order of Fit is when an individual’s activities help to reinforce what other providers know and are doing to achieve the group’s/team’s expectations. This underlines the importance of having senior team members adhere to team norms.

-

Third order of Fit is where there is an optimization of effort on the part of all Providers and associated systems to meet team and system expectations.5

Providers need more than a skill set to fit into a team strategically. Therefore, before opting to be in hospital medicine and a particular team, one needs to answer these questions reflectively:

-

Is inpatient medicine what I want to pursue?

-

Do have I the breadth of medical knowledge and collaborative skills this job requires?

-

Do I like the work environment of the specific group/team in view of the group’s/ team’s operational activities?

It is acceptable for individuals to explore the option of being in hospital medicine without a clear sense of long-term commitment. However, they should at least be committed to the set goals and objectives for the duration of their brief exploratory period. One needs to pursue what resonates with their inner values to be successful. This decision should not be based solely on the opinions of others or on the perceived allure of work-life balance and financial compensation in hospital medicine.

Decisions made solely on perceived gains without a resonance with inner self attributes and a thorough evaluation of job requirements cannot withstand the inevitable turbulence of hospital medicine and, as such, any other career in medicine.

Successful Teams

Hospital medicine requires unique skill sets in the areas of the breadth of medical knowledge, collaboration with other group/team members, and other services. The ability to work collaboratively to enhance patient care and patient throughput is a critical success factor. Inability to work collaboratively with colleagues and with other healthcare providers severely hampers growth in this field. The varying work environment and expectations in hospital medicine require personal evaluation from all potential and current providers to ascertain their strategic fit in their work environment. A conducive environment is required for the Third order of Fit to be evident.

The success of any venture that depends largely on teamwork is invariably due to multiple factors. What makes teams TICK?

-

Team concept and its associated goals ought to be key founding principles.

-

Incentives for meeting goals for the group and for outstanding physicians

-

Communication to ensure appropriate hand-offs with all stakeholders.

-

Knowledge diffusion- to help maintain the quality of care provided.

Communication is critical for the creation of the required buy-in from all providers. Ongoing communication about all changes in vision, operational changes, and/or set goals is required to maintain the required fit from all providers. In addition, a forum for exchanging ideas about these changes helps to enhance the required buy-in and helps to enhance self-actualization.

Opportunities for education to enhance skill sets should also be made available. These are required to move from the First and Second orders of Fit to the Third order, where optimization of efforts is actualized. All highly functional groups/teams aim for the Third order of Fit. Quiet quitting is a phenomenon that needs to be addressed early in order to avoid its potentially devastating effects. Therefore, measures to achieve the third order of Fit are needed to address it.

DISCLOSURES/CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All Authors (KDA, PG) have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission.

All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the ICJME criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie, MD

Professor of Medicine, Clinician Educator Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University

Division of Hospital Medicine

The Miriam Hospital, 164 Summit Avenue, Providence, RI 02906

Tel: 401-793-2104 Fax: 401-793-4047

Email: kdapaahafriyie@lifespan.org