Background

On April 26,2020, Dr. Lorna Breen, the medical director of New York Presbyterian Allen Hospital’s emergency department, died by suicide. Her father reported that just prior to her death, Dr. Breen, who had never previously been diagnosed with a mental health condition, had described horrific scenes of patients dying from COVID-19.1 In the United States, frontline healthcare workers have suffered tremendous morbidity and mortality from COVID-19, both from contracting the virus, with over 100,000 healthcare workers dying from COVID-19 in the first 18 months of the pandemic as well as the emotional toll it has taken.2,3

Similar to previous outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed great strain on health care systems worldwide with a significant negative impact on staff wellbeing.4 Prior research confirms healthcare workers on the frontline of epidemics are at increased risk of burnout, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and may also be at higher risk of suicide.5–7 The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered PTSD not just in patients and the general population but also in health care workers.8

A study of healthcare workers in New York uncovered frequent symptoms of acute stress, depression, and anxiety during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.9 Another study found the burnout level in frontline nurses in Iran was higher than other nurses on the general wards with the most important influencing factor being job stress.10 Dugani and colleagues observed among hospitalists lower global well-being, an increase in anxiety and social isolation, and a small decrease in emotional support during the pandemic.11 Similarly, Mental Health America reported high levels of stress, anxiety and emotional exhaustion in healthcare workers.12 In February 2020, a cross sectional study of female health workers in Wuhan, China demonstrated that a high proportion of women health workers experienced stress, depression and anxiety during the early stages of pandemic.13 Prior epidemics have suggested the psychological impact may be higher for female health workers than for male counterparts.14

While most previous studies on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers have focused on single professions, a few have examined stress and anxiety differences between genders and professions in the intensive care unit or at the university level.10–13,15–17 Describing and understanding how different professionals in the same environment and at the same time may be experiencing the pandemic can help teammates empathize with and support each other. Accordingly, we sought to better understand how physicians and nurses may experience the COVID-19 crisis similarly or differently as well as how gender may impact their experiences. Knowledge of how these two key frontline professions may be experiencing the rigors of the pandemic can provide a deeper mutual understanding to inform potential interventions to improve teamwork, morale, and well-being in future crisis situations.

Methods

Between July 17, 2020, and October 31, 2020, we surveyed critical care and medical-surgical ward nurses as well as hospital medicine and critical care faculty physicians caring for COVID-19 patients at a large urban, academic, safety net hospital in southwest United States.

Similar to previous published studies in this area, survey questions were adapted from validated questionnaires used to determine quality of life (Professional Quality of Life Tool), assess levels of anxiety (General Anxiety Disorder-7), and evaluate the impact of stressors such as COVID-19 on domains of work, home/family and social lives (Sheehan’s Disability Scale).11,12,18–21 Adaptations were made to tailor the survey to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in the Sheehan’s Disability Scale, we adapted one question from “the symptoms have disrupted your family life/ home responsibilities” to read “I’m worried that being a healthcare worker during the COVID-19 crisis will adversely affect my family life/ home responsibilities.” Surveys were administered electronically via Qualtrics to 11 critical care and 67 hospital medicine faculty as well as an estimated 210 nurses (excluding float pool nurses that may have inadvertently received the survey).

Descriptive statistics were performed. Means, medians, standard deviations, and inter-quartile ranges were reported for continuous variables. Categorical variables were described through frequency distributions. Kruskal-Wallis tests and Chi Square tests of equal proportions were used to assess differences in survey responses and demographics among the professions and genders. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. SAS version 9.4 was used for statistical analyses.

All study procedures complied with the ethical standards of the University of Texas at Southwestern IRB (Institutional Review Board) guidelines, protocol number: STU-2020-0439 Velos #: 30417.

Results

Overall, 41.7% (120 of 288) responded to the survey, including 50% (39 out of 78) of physicians and 38.6% (81 out of 210) of nurses. Of the 81 nurses who responded to the survey, 75 (92.6%) are female compared with 17 (43.6%) of the 39 physicians responding to the survey (p <0.01, Table 1). Forty-three (53.1%) nurses and 32 (81.9%) physicians were frequently caring for patients with active COVID-19 (p<0.01). The median ages of physician and nursing respondents were 35 (IQR 32 to 39) and 31 (IQR 26 to 40) (p=0.01), respectively. Of the physicians, 71.8% lived with a spouse compared with 43.2% of nurses (p<0.01), while a minority of both physicians and nurses lived alone (12.8% vs 13.6%, respectively, p= 0.91). The majority of both physicians (59.2%) and nurses (53.8%) did not live with children (p=0.57). 33.3% of physicians lived with children aged 5 or younger and 24.7% nurses lived with children aged 6-17. Only 2.6% of physicians and 2.5% of nurses lived with elderly relatives at home (p= 1.00) or their parents (5.1% of physicians vs 18.5% of nurses, p<0.05). Physicians were more likely to seek support from a spouse than nurses (71.8% vs 43.2%, p < 0.01). Additionally, both groups equally reported seeking support from friends (64.1% vs 55.6%, p= 0.37), parents (33.3% vs 44.4%, p=0.25), and other family members (35.9% vs 46.9%, p=0.25).

Quality of Life

Physicians and nurses were equally preoccupied with patients they provided care for (46.4% vs 44.1%, p= 1.00) and similarly satisfied with being able to provide medical assistance to people (70.8% vs 68.6%, p= 0.85). (Table 2 - supplemental) They expressed similar rates of feeling affected by traumatic stress from their patients (18.9% vs 15.1%, p= 0.61) and rates of feeling trapped as a healthcare worker during the pandemic (18.0% vs 26.5%, p=0.32). Physicians and nurses were also equally likely to feel they can make a difference through their work (45.2% vs 49.1%, p=0.72) and happy they chose to do this work (53.1% vs 60.0%, p= 0.37), while the minority of both professions felt successful as healthcare providers (34.2% vs 29.9%, p=0.64).

Male nurses were more likely than female nurses to report losing sleep over a patient they were caring for (33.3% vs 5.7%, p= 0.02). A similar proportion of male and female nurses felt overwhelmed by their case load (40.0% vs 24.2%, p= 0.43), but also similarly happy they chose this work (50.0% vs 60.4%, p= 0.58). Female physicians were more likely than male physicians, female nurses and male nurses to report finding it difficult to separate their personal lives from their lives as healthcare workers during the pandemic (84.6%% vs 35% vs 35.9% vs 33.3%, p <0.05). Fewer male physicians perceived themselves as a very caring person when compared to female physicians and female nurses (42.1% vs 72.7%, p= 0.01 and 42.1% vs 75%, p= 0.01). Female physicians were also more likely than male physicians to report having beliefs that sustain them (81.8% vs 36.8%, p= 0.02).

Work, Home, and Social Life

Physicians and nurses felt equally concerned that COVID-19 would adversely affect their family life (70.3% vs 68.8%, p= 0.88), disrupt their social lives/leisure activities (81.1% vs. 74.0%, p= 0.41) and create household financial strain (24.3% vs 32.5%, p= 0.37, Table 3 - supplemental). Approximately 60% of nurses in our cohort reported worries of being excluded from social gatherings or leisure activities due to their profession, compared with 35.1% of physicians with similar worries (p= 0.01). Similarly, 70.1% of nurses expressed significant concerns over unknowingly exposing friends or community members to COVID-19 in contrast to 46.0% of physicians (p= 0.01). Nurses were more worried about being treated differently by others when compared to physicians (64.5% v 37.8%, p < 0.01).

Female nurses were more likely than female physicians to feel people would exclude them from gatherings (60.6% vs 29.4%, p= 0.02), more likely to worry that they may unknowingly expose friends or community members to COVID-19 (71.8% vs 41.2%, p= 0.02), and more likely to worry that they are putting themselves at undue risk (65.7% vs 29.4%, p <0.01).

Levels of Anxiety

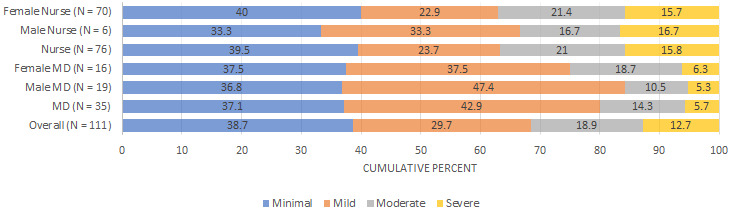

Physicians and nurses experienced similar levels of moderate (14.3% vs 21.2%, p=0.40) and severe anxiety (5.7% vs 15.8%, p= 0.14, Figure 1). Additionally, when moderate and severe anxiety groups were combined, no significance was found in comparing physicians and nurses (20% vs 36.8%, p= 0.078). Furthermore, no difference was detected between physicians and nurses after combining those with minimal and mild anxiety (80% vs 63.2%, p= 0.078). Overall, 89.7% of physicians and 93.8% of nurses reported some level of anxiety. We found no statistically significant differences in anxiety levels based on gender.

Discussion

COVID-19 has had a broad and deep impact on our society as a whole and health care workers in particular, ranging from financial uncertainty to social and professional upheavals.5,6,10,11 Widespread misinformation has eroded trust in health care and science, creating further challenges to healthcare workers at home and in their communities.22,23 Our study of the experience of physicians and nurses in a large, academic public safety-net hospital during the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a high level of disruption to their home/ family and social lives in addition to widespread impact on their emotional and financial well-being.

Both nurses and physicians of both genders experienced a high prevalence of generalized anxiety and concern for their financial health. Nurses expressed greater worry than physicians about accidentally transmitting COVID-19 and being treated differently by community members, with female nurses expressing an even greater concern over male nurses.

The pandemic brought on a level self-doubt and lack of expertise rarely experienced by a highly trained and skilled health care workforce who were suddenly tasked with caring for patients afflicted with a novel contagion. In fact, a survey of over 2,700 U.S. physicians of various countries and specialties, found that less than half felt adequately prepared for the pandemic, personally or professionally.24 In our study, the majority of nurses and reported being happy with their profession and feeling satisfied that they were making a difference in their line of work. At the same time, most participants reported not feeling successful as healthcare providers. The reasons for these feelings of inadequacy are unclear, however, both survey studies occurred before there were any disease specific targeted therapy options or vaccines available for COVID-19.25,26

A high proportion of frontline physicians in previous studies8 during COVID-19 had developed pandemic grief associated with the death of patients, colleagues, and their own loved members.27,28 Approximately a fifth to a quarter of physicians and nurses were affected by the traumatic stress of their patients and felt trapped as a healthcare provider in the pandemic. Furthermore, female physicians found it more difficult to separate their personal lives from their lives as a healthcare professional in comparison to female nurses, male nurses, and male physicians. This may correlate with our findings that female physicians view themselves as more caring than male physicians. Additionally, previous work has demonstrated that a disproportionately percentage of women physicians have shouldered domestic as well as childcare and educational responsibilities.29 Women have been forced to decrease their work hours four to five times more than men due to childcare during the pandemic.30,31

A previous study of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic, found that potentially hurting family members and the feeling of being excluded led to distress.32 Additionally, the way healthcare professionals have been educated and the roles they play on their health care team may influence differing coping strategies in times of stress and crisis.33 Across both professions, the pandemic had a similarly high impact on home/ family and social life, with nearly 70% of nurses and physicians expressing concern that being a healthcare worker during the COVID-19 crisis would adversely affect their home/ family responsibilities. While about three quarters of both nurses and physicians reported disruptions to their social life and leisure activities, nurses were more worried than physicians, by almost a two to one rate, about being excluded from social gatherings or being treated differently. Additionally, over 70% of nurses were concerned about infecting their friends or community while less than half of physicians shared the same sentiment. This discrepancy between physicians and nurses may be a reflection of differential risk assessment that stems from systems of training and role responsibilities on the health care team.33

While numerous studies have examined the way different genders in the same profession experience crisis situations, less is known about how same genders experience crisis in different professions.15–17 In our study, when observing same gender but different professions while both female nurses and physicians experienced a high prevalence of anxiety, we found that female nurses were more likely than female physicians to feel excluded from gatherings, worry about unknowingly exposing their friends, colleagues, or community to COVID-19, and worried more about putting themselves at undue risk while at work. A systematic review and meta- analysis of nearly 20,000 nurses also found that high levels of decreased social support and increased perceived threat of COVID-19 had a negative impact on well-being.34 Furthermore, they found this could be attributed to longer working time in quarantine areas, increased workload and lower level of specialized training regarding COVID-19.34 Interestingly, for these same concerns, no significant difference was found between male nurses when compared to male physicians.

In the United States adult population, diagnoses of anxiety have been on the increase in the ten years prior to the COVID pandemic.35 By 2019, 84.4% of U.S. adults were categorized as having none or minimal anxiety symptoms, 9.5% were categorized as having mild anxiety symptoms, 3.4% were categorized as having moderate anxiety symptoms, and 2.7% were categorized as having severe symptoms.36 Pappa and colleagues performed a meta-analysis on COVID-19’s effect on healthcare workers’ prevalence of anxiety and depression. They found a high pooled prevalence of anxiety (23.2%) and depression (22.8%) among health care workers during COVID-19, especially among women and nurses.37 In contrast, we did not find increased levels of anxiety based on gender or profession. We identified nearly 90% of physicians and over 90% of nurses as having some level of anxiety, with 20% of physicians and 37% of nurses experiencing moderate or severe anxiety. Our study was conducted after the initial wave of COVID-19 had subsided. Accordingly, it is possible that there were higher levels of moderate and severe levels of anxiety at the onset of the pandemic.

This study was limited by response bias, as the survey was voluntary and sent by email. As it took place at a single center, it may not be generalizable to other institutions. The survey was conducted once and during a finite period and thus may not fully reflect the degree of variability in perceptions of healthcare workers throughout the pandemic. While our survey included non-binary gender identity as a field, we did not have any respondents identify as non-binary in gender. Accordingly, this group was not represented in our study. Additionally, to maintain anonymity differentiation of intensivist and hospitalist was not established, and our findings may not be generalizable to each field. Lastly, while our survey questions were adapted from validated surveys, the modifications prevented us from analyzing the data according to previously described methods.18–21

Future directions may include the longitudinal monitoring of health care workers’ emotional wellbeing to further understand how health care workers are affected in different phases of a prolonged crisis. Qualitative studies may also help elucidate the triggers for the different concerns expressed in the surveys as well as form the basis for potential interventions to support health care workers. Including other professions and extending studies to multiple institutions are also indicated.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has had a significant toll on the emotional well-being of health care workers. In our study on nurses and physicians in a large, urban, academic hospital, we found that COVID-19 has had far reaching effects, from diminishing feelings of self-efficacy at work to extending beyond the hospital into home, family and social situations, all couched in a pervasive anxiety and concern for social and financial wellbeing. Understanding how different professions and genders experience the COVID -19 crisis promotes mutual understanding and wellbeing amongst the frontline healthcare teams.

Disclosures/ Conflict of Interest

No disclosure or potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This study was supported by funding from the Division of Hospital Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine at University of Texas at Southwestern. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the help of Lonnie Roy (Parkland Hospital), Hane Hong (University of Texas at Southwestern) for assistance in table generation.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

-

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Satyam Nayak MD MPH

University of Texas at Southwestern School of Medicine

5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75390

Phone: 214-648-9741

Email: Satyam.nayak@utsouthwestern.edu