The inpatient environment is much different now compared to the time when the term “hospitalist” was coined. In 1995, amidst a rapidly changing and complex inpatient medical environment, the field of hospital medicine was formally launched and gained traction.1 Gains made by hospitalists in the areas of patient care, patient throughput, and patient experience have been acknowledged and embraced by patients, outpatient providers, and other stakeholders within the broad healthcare system. Health management organizations (HMOs) have leveraged these potential benefits by operating their own hospitalist programs, although physician organizations and healthcare systems/hospitals are responsible for operating most groups.

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing events have led to an erosion of trust in the healthcare environment. The singular effect of misinformation regarding health care dispersed via social media cannot be overemphasized. As a result, hospitalists, nurses, and other “front-line” providers are exposed to increased anger, distrust, and hostile behaviors from the populations they serve. (Need source). Clinical care of hospitalized patients, especially those with severe disease, is often complicated by the expectation of quick turnarounds and positive outcomes by both patients and families/advocates, oftentimes unrealistic and not rooted in reality. This desire, in the setting of interactions with hospitalists who are largely unknown to them and sometimes from a diverse background, adds to mistrust when information conveyed and/or events do not fit a narrative they have heard and have come to expect. Expressions of gratitude for the care provided have subsequently begun to disappear from the inpatient environment.

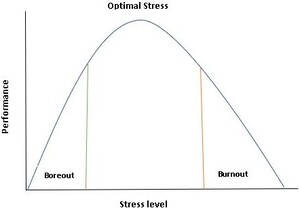

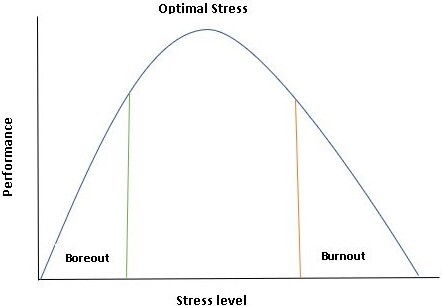

Burnout is a syndrome characterized by high emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (i.e., cynicism) and a low sense of personal accomplishment at work.2 The downstream effects of burnout include devastating consequences for the health of clinicians, patient outcomes, medical education, and productivity in our healthcare systems. The prevalence of burnout amongst the healthcare workforce has gained attention over the past few years, although remains a major concern due to workforce attrition amid increasing demand for these skill sets in the inpatient setting. (Need source). Among many variables, a combination of increasing demands in the workplace and lack of, or perceived lack of, appreciation of the value of healthcare workers strongly contributes to burnout (Figure 1).

Burnout among physicians and nurses was termed an “international crisis” in 2016, existing well before the COVID-19 pandemic and was dramatically exacerbated due to unprecedented stress and change imposed on the inpatient environment.3 Currently, about 52% of nurses (according to the American Nurses Foundation) and 20% of doctors (Mayo Clinic Proceedings) say they are planning to leave their clinical practice. Shortages of more than one million nurses are projected by the end of the year (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics); a gap of three million low-wage health workers who provide much of the hands-on patient care is anticipated over the next three years.3

In 2017, the National Academy of Medicine launched the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, committed to reversing trends in clinician burnout. The Clinician Well-Being Collaborative has three goals:

-

Raise the visibility of clinician anxiety, burnout, depression, stress, and suicide.

-

Improve baseline understanding of challenges to clinician well-being.

-

Advance evidence-based, multidisciplinary solutions to improve patient care by caring for the caregiver.

While burnout has detrimental effects intrinsically, the extrinsic effect of burnout manifests themselves as a serious threat to the nation’s health and economic security. The need to identify the major causes and institute required changes led to the US Surgeon General’s advisory on health worker burnout and well-being, issued on May 23, 2022.4 Burnout manifests in individuals, but it is fundamentally rooted in the interfacing of the system with individuals in the healthcare environment. Many external and internal factors account for decreasing job satisfaction in hospitals and the ensuing effects on the well-being of hospitalist providers, as outlined below:

External factors

-

Misinformation and misperception: Patients and families have access to many forms of misinformation via social media, which breeds unrealistic expectations in the inpatient setting. Those who opt for “concierge” services in the outpatient domain may not realize that hospitalists triage patient care services based on diagnosis and acuity of clinical conditions. Outpatient concierge services do not automatically translate to concierge hospitalist services.

-

Although mostly explicit, insurance care plans offered by HMOs may not always be fully understood by patients and families. These plans determine the level of care status (inpatient versus observation) covered services, medication co-pays, and other patient disposition plans. Not understanding these covered services may lead to contention with case managers and hospitalists during the coordination of discharge care.

-

Initiatives from the Center for Medicare Services (CMS) and other regulatory bodies aiming to alter inpatient metrics and guidelines, although laudable in helping optimize care in the inpatient setting, have sometimes created undue burdens and redundancy for hospitalists.

-

Information overload: Preliminary information given to patients/families by PCPs, emergency medicine, and other providers before admission to the inpatient setting may not be accurate. Hospitalists bear the burden of addressing and clarifying information provided to patients and families during their initial presentation to the emergency department and throughout the entirety of their hospitalization. A typical scenario is the case of a patient initially misdiagnosed with pneumonia ending up with lung cancer, leading to angst on the part of patients and families. Discrepancies in patient disposition plans based on initial information from the emergency department are another area of contention.

Internal factors

-

Hospital environment: The increasing demands of electronic health records (EHRs) and frequent use of various pop-up alerts is a continuing source of frustration and mental fatigue. These strategies, although well-intended, extend the time required to place inpatient orders and manage overall patient care. Many systems have recognized this issue and are taking steps to make EHRs more user-friendly.

-

Documentation: Clinical documentation initiatives adopted by most healthcare systems to meet regulatory requirements and optimize facility billing have resulted in numerous requests to hospitalists to make changes to notes even after patients have been discharged. Using specific language related but not equivalent to terms used in clinical communication to meet these documentation requirements is daunting.

-

Professional relationships: Hospitalists are required to work collaboratively with many other clinicians to enhance patient care. This is especially important in co-managed models of inpatient care (inpatient oncology, orthopedic fractures, etc.). A lack of collaboration and inadequate communication about patient care plans also results in suboptimal interactions with patients and families.

-

Group culture: Hospitalists need a nurturing and supportive environment to work collaboratively to achieve set goals. Groups that encourage undue competition for relative value units (RVUs) and other unhealthy professional practices negatively affect hospitalists’ morale, especially for new members. Mutually beneficial group norms need to be set by leaders to help build cordial and productive relationships.

These internal and external factors have an appreciable effect on the stress faced in the inpatient setting. This stress in turn has a negative impact on overall wellness, which inevitably decreases productivity.5 Clinician well-being enhances patient-clinician relationships and builds a high-functioning care team resulting in an engaged and effective workforce. Supporting clinician well-being requires sustained attention and action at organizational, state, and national levels and investment in research and information-sharing to advance evidence-based solutions. In addition, more steps should be taken to address the information gap on burnout treatment and prevention by professional bodies and medical societies.

There are several steps that can be taken to help mitigate burnout. Discharge managers should reiterate pertinent aspects of insurance plans and covered services within 24-36 hours of the patient’s admission to the hospital, so as to curtail the development of unreasonable patient expectations as it pertains to disposition. Enhanced collaboration between colleagues in the emergency department and inpatient setting will reduce patients’/families’ frustration due to gaps in communication. Metrics from regulatory bodies and hospital leadership should prioritize patient care and be achievable without being burdensome. And finally, electronic health records should be less burdensome to use and less prone to the development of “click fatigue.” While EMRs are the new norm, they will not magically eliminate the documentation required for billing and regulatory compliance. Some institutions are taking steps to make their EHRs more user-friendly while others are working with physicians to eliminate redundancies and make EHRs less burdensome through programs such as the American Medical Association’s (AMA) “Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff.”6 Regardless of which approach is chosen, a combination of all of these aspects will result in a tremendous improvement in both the quality of care for patients and decrease in burnout for providers.

Burnout is not only about long hours spent at work but also the fundamental disconnect between healthcare workers and the mission to serve that motivates them. Therefore, in addition to the above measures, there must be a renewed emphasis on mental health to help address specific but pervasive issues, including anxiety, depression, and coping skills, amongst individual hospitalists.

Hospitalists should remember the following:

-

We need sanity in other aspects of our lives to be effective as hospitalists. Our personal lives also require us to be organized and productive.

-

We need to seek professional opportunities in other hospitalist programs if the pace of work in our current practice is faster than we can handle.

-

All roles have an end; nothing is permanent. Sometimes we need to transition to other roles to maintain our well-being.

-

We must strategically use wellness techniques such as enjoyable vacation time, yoga, and other modalities.

“My legacy is that I stayed on course …. From the beginning to the end, because I believed in something inside of me.” Tina Turner (1939-2023).

Corresponding Author

Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie, MD

Professor of Medicine, Clinical Educator

Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University

Division Director

Division of Hospital Medicine

The Miriam Hospital, 164 Summit Avenue, Providence, RI 02906

DISCLOSURES/CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.