The COVID-19 pandemic and its enduring effects on inpatient care and the associated “moral injury” on healthcare providers have placed a renewed emphasis on leadership in hospital medicine.1 “Great Resignation” refers to the increased rate at which workers in the United States resigned from their jobs starting in the spring of 2021, amid strong labor demand and low unemployment even as vaccinations eased the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic.2 Anthony Klotz, a professor of business administration at Texas A&M University, coined the term in May 2021. “Quiet quitting” was described in a September 2022 Harvard Business Review article: “Quiet quitters continue to fulfill their primary responsibilities, but they are less willing to engage in activities known as citizenship behaviors: no more staying late, showing up early, or attending non-mandatory meetings.” Having primarily been spared the adverse effects of the Great Resignation, “quiet quitting” continues to exert a toll on all aspects of hospital medicine practice.

The demand for hospital medicine to continue working on streamlining inpatient operations to become more agile and efficient in our post-pandemic era requires new insights into established leadership concepts. Adopting strategic vision, outlining, and communicating goals are still critical. However, an equally important concept is sustained engagement, which has been catapulted forward due to the need to overcome the emotional trauma and lingering effects of moral injury due to COVID-19.

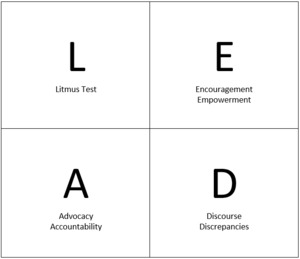

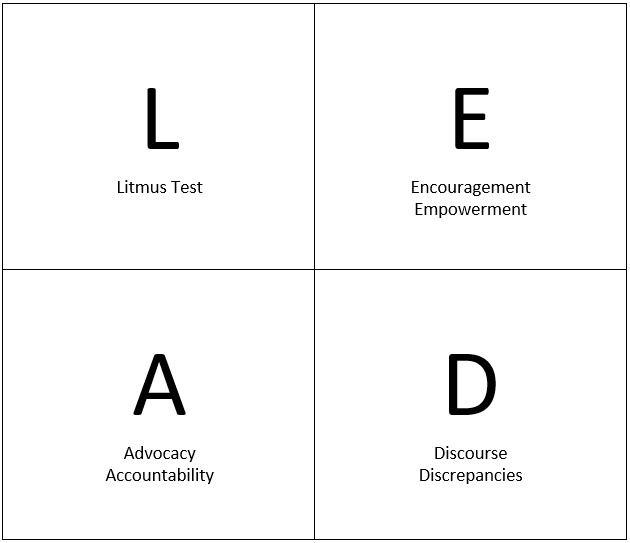

The need for puissant leadership is a critical component of engagement. It is required of leaders to LEAD (Figure 1)

L: The Litmus test. Passing this test is required to secure sustained engagement and buy-in to maintain and enhance hospital medicine operations. Leaders rise or fall based on their performance on the trust scale. No one can achieve a long-lasting buy-in from colleagues if they cannot be trusted. In his book “The Speed of Trust,” Stephen Covey states that trust has two components: character and competence.

Administering the litmus test: What is the basis of the leadership role? What do you bring to the table as a leader? Why do people come to you and work with you? In addition to basic managerial skills, all successful leaders have a reputational asset that they build upon to attain pertinent leadership skills. These assets are attained through a proven track record of stellar clinical work, operations management, and academic work. This has been the basis for successful leadership in academia for decades and helped give credence to the nascent field of Hospital Medicine in the late 1990s. The L is not just for intangibles like longevity, loquaciousness, and listening skills. Reputational assets are foundational to achieving buy-in, the cornerstone to meeting set goals. Leaders who fail to pass the litmus test must be astute in creating a highly functional leadership team with the required reputational assets to succeed in their environment. Venture capitalists, another group of decision-makers operating under uncertainty, require assembling a team of experts with required skill sets in the specific areas of interest to pass the litmus test and succeed in their endeavors.

E. After the litmus test, the adoption of Encouraging and Empowering measures is needed. The need for measures to ensure ongoing encouragement cannot be overemphasized. Leaders cannot effectively encourage team members if they are unaware of the required tasks’ key dimensions, including routine clinical activities such as admission, follow-up, and discharge of hospitalized patients. A quote by Pope Francis, the Bishop of Rome, Pontifex Maximus (elected 2013): “The shepherd should smell like his sheep,” applies in this encouragement domain. Leaders should be aware of the tasks required of their team members and the steps to achieve them successfully. The value of team members cannot be effectively appreciated and expressed without sharing in members’ challenges and anxieties. Understanding the unique challenges of inpatient throughput on weekends when many regular services are delayed or unavailable is a good example. Leaders can effectively address the challenges and convey the importance of this critical patient metric to their colleagues by being involved in the clinical work. Leaders should assume their fair share of clinical work and avoid the impression that they are ‘allergic’ to weekends at the hospital. The need for group camaraderie is crucial to sustained engagement. Failure to know about one’s hospital operations is a failure of leadership, which can rapidly leech away trust. Respect is earned by walking into the trenches and when “shepherds smell like their sheep.”

Empowerment of team members is a requirement to buttress and reinforce buy-in from them. This can be best accomplished when members know the basic guidelines of clinical operations. This empowers them to make operational decisions and, more importantly, to come up with suggestions based on changes in the work environment. Some groups continually revise their systems for new patient assignments to physicians on rounding shifts to ensure fairness without penalizing those with higher discharge efficiency metrics. Such initiatives should not be stifled but rather encouraged so far as their basis conforms with the group’s goals.3 Decisions taken affect operational effectiveness and reflect the group’s activities. Leaders need to trust their colleagues to make decisions. Lack of trust can lead to indecisiveness and cripple operations; a unipolar system should be avoided. As per Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States: “People when rightly and fully trusted will return the trust.” However, mistakes will occur because there are unique perspectives that not all members will consider when initiatives are taken, or suggestions/decisions are made. These mistakes should, however, form the basis for mentorship. Review of triage admission decisions, particularly when involving other inpatient services (intensive care, surgical), may help group members appreciate the importance of established admission guidelines and co-management models with surgical specialties.

A: Leaders need to Advocate for their team members and hold them Accountable.

Advocacy: Leaders are the bridge between executive “C-suite” and clinicians. There will always be requests from administrative leaders for new metrics and changes in operations: this is not a one-way street. Advocacy requires listening to and channeling the concerns of the hospitalist team to management within the C-suite. Leaders need to ensure requests from the C-suite are attainable and help create win-win situations when disagreements between these requests and the team’s goals. A good example is interdisciplinary rounds, which must be streamlined and efficient to create desirable outcomes for all stakeholders. Including a 1–3-month trial period for new initiatives/ideas followed by reevaluation to assess their impact may allow smoother integration into existing operations while weeding out those changes that impede existing efficiencies.

Goal congruence is critical for success; leadership is needed to help bring pieces together. Morale is negatively affected by incongruent goals and a lack of resources to meet set goals. Requests for assuming additional clinical work should always be backed by the provision of adequate resources and prompt availability of sub-specialty services needed. Expectations from new service requests need to be codified to prevent ambiguity. There is also a need for buy-in from other stakeholders. The morale of team members is an essential requirement for attaining new goals. Steps to make team members feel valued and appreciated are essential morale-boosting measures. Some leaders have used small gifts or surprise lunch/dinner meetings to achieve this goal.

Accountability: “Setting a goal is not the main thing. It is deciding how you will go about achieving it and staying with the plan” - Coach Tom Landry (1924-2000). There is a need to balance too much scrutiny and lack of oversight. Accountability separates high performers from the pack. It also forms the foundation for a winning culture because people innately want to be challenged to improve. Metrics should be established and known to team members. These metrics should be reviewed annually or biannually to assess performance and ensure compliance. Holding team members accountable by adjusting compensation based on compliance with required metrics sends a message about their importance. This also “levels the playing field” among group members as the metrics for success are spelled out in black and white. It is of utmost importance that leaders should subject their clinical work to the same standards. Personal compliance with applicable performance metrics ensures team members will respond appropriately to attain set goals.4

D. Lastly, steps should be taken to ensure adequate Discourse about expectations and to deal with performance Discrepancies.

Discourse: A clear sense of clinical responsibilities, assignments, and the basis for rotation assignments should be delineated and communicated to the team members. Due to the potential adverse effects on efficiency and job satisfaction, decisions about shift assignments should be made based on merit and skill sets to meet set goals. The importance of adequate and good communication is well known and continues to be the bane of leaders who fail to achieve the required buy-in to ensure that the members clearly understand their objectives and values. Adequate and timely communication also creates a forum for feedback and input for changes to be made. Timely feedback is the “breakfast of champions.” Lapses in core functions such as medication reconciliation and timely communication of discharge summaries to referring physicians can be communicated constructively to junior and senior group members. Weekly e-mail messages and at least scheduled monthly group meetings ensure timely and adequate communication between team members.

Discrepancies: Lapses in patient care, non-adherence to the team’s metrics, and other objectives have a cumulative and often irreversible harmful effect on group performance. These and all other lapses need to be addressed promptly, especially when the culprits are senior members of the group. Longevity in the group should not be the basis for exceptions in meeting basic team objectives. Instead, they are required to help set a higher standard for the team. Making repeated exceptions or glossing over repeated lapses erodes leaders’ ability to provide effective leadership and creates “room for interpretation” amongst junior group members. The repercussions for all patient care lapses should be addressed per group norms. Any form of bias in addressing discrepancies breeds discontent and division.

Leaders must LEAD; this is what team members expect to attain the buy-in required to meet set goals. Leaders must work hard; everyone expects that from their leaders. Working harder and putting in extra effort inspires the team members. New opportunities become available to leaders who work hardest and demonstrate the ability to accountably self-administer the “litmus tests” of leadership over time.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding author

Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie, MD

Professor of Medicine, Clinical Educator

Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University

Division Director,

Division of Hospital Medicine,

The Miriam Hospital,

164 Summit Avenue, Providence, RI 02906